A Degrowth Future for the Arts?

In this digital residency in collaboration with Érudit, Sophie Dubeau Chicoine explores the potential of degrowth as a practice in the arts, focusing on the ways in which degrowth can contribute to the well-being of local and artistic communities. The digital residencies were made possible with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

In the spring of 2024, hundreds of artists and cultural workers gathered in the streets of Montréal to demand better provincial funding for the arts. Without adequate funding, the cultural sector has no choice but to intensify its efforts to maintain its programming, further exhausting members of the profession. In its press release of May 3, 2024, the Grande Mobilisation des artistes du Québec reiterated the urgent need for an additional $100 million in financial aid “to absorb rising costs, maintain our resources and skills, hold on to our staff, and allow us to grow.”1 1 - Grande Mobilisation des artistes du Québec, “La grande manifestation pour les arts #2,” Réseau Art actuel (May 3, 2024), reseauartactuel.org/grande-manifestation-pour-les-arts-2-le-jeudi-16-mai-a-15h/ (our translation). In perpetual anticipation of this government support,2 2 - In mid-May, the minister of culture and communications, Mathieu Lacombe, announced an increase of $15 million for the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec’s mission support program, an amount that fell well short of the requested $100 million. it seems fitting to reflect on what we collectively mean by “grow.” Do we wish to increase our financial resources in order to generate still more material and energy resources in return? Not only does this strategy hinder our environmental goals but it offers no relief to our already exhausted colleagues and collaborators. On the other hand, what if the increase in our financial resources served, at last , to radically transform our working practices? During this digital residency, I took on the mission of imagining an alternate future for the arts, one based on degrowth. While going through the digital archives of both Esse and Érudit, I came to realize that hints of degrowth already exist in the Québec landscape, in the productions of artists, cultural practitioners, and ephemeral exhibition venues.

The Call for Degrowth

Western capitalist imaginary assumes the possibility of infinite production and consumption in a world in which resources—human, material, energy—are in fact finite. In contrast, degrowth proposes a relational economy aimed toward collective wellbeing, within planetary limits. On a policy level, some of the most publicized of these demands concern the establishment of a universal basic income and a shorter work week. At a community level, many initiatives participate in the creation and maintenance of networks of care, inspired by certain feminist groups and mutual aid services. These various engagements are intended to imagine what our professional and social lives might look like beyond the options given by the public and private sectors. I believe this affective and speculative dimension makes degrowth a fertile and transformative terrain for the arts sector.

Degrowth implies reconfiguration of what we mean by “mutual aid,” envisioned not as a commercial transaction but as a pooling of knowledge. Degrowth also aims to slow down our frenetic pace of production, a respite not to be confused with imposed austerity. On the contrary, degrowth is based on a planned process by which we collectively decide what needs to be slowed down in order to move forward. To generate real change, degrowth cannot be performative; it must be embodied, active, and participatory. In their article “Pour en finir avec la dictature du ‘toujours plus’: l’art de la décroissance,”3 3 - Ariane Daoust and Aline Ginda, “Pour en finir avec la dictature du ‘toujours plus’: l’art de la décroissance,” Espace, No. 125 (Spring–Summer 2020): 44–49, accessible online. Ariane Daoust and Aline Ginda discuss the case of the artist Jean-François Prost (via Adaptive Actions) and his project, Stopping/Arrêts, 6919 Marconi (2019), the address of a vacant lot that he acquired and opened to all for multiple uses: parties, film screenings, urban gardens… By refusing to surrender the plot to real estate speculation, Prost transforms its exchange value into usage value, contributing to social rather than economic wealth. Daoust and Ginda see this project as an invitation to reimagine our social relationships outside the paradigm of private property. 6919 Marconi Street thus creates an interstice for constantly changing encounters shaped by the engagement of participants who meet there, whether intentionally or by chance. At the very least, the project brings people together. To collectively imagine what a radical transformation of the artistic environment might look like, first we must find such meeting places.

Collaboration

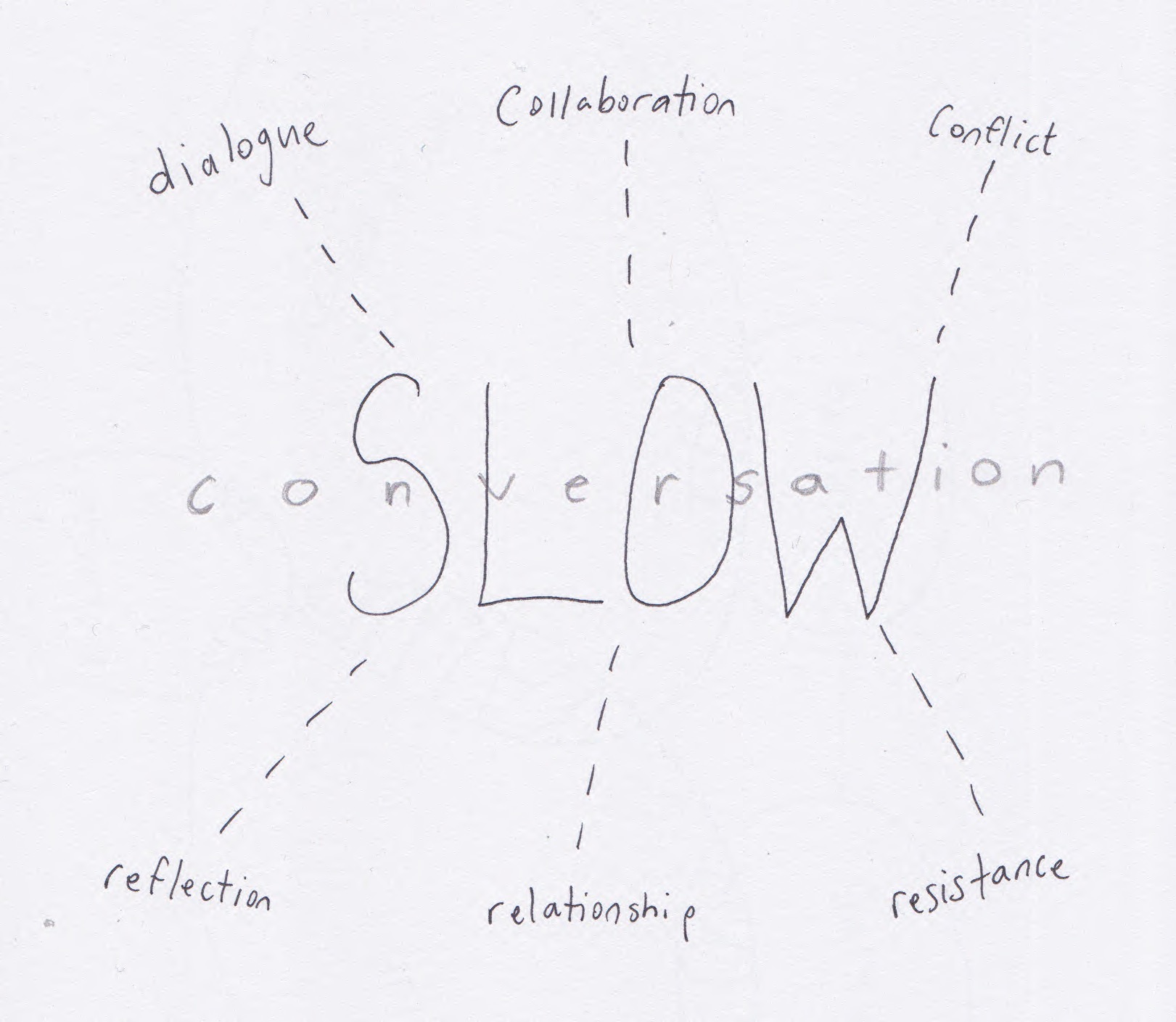

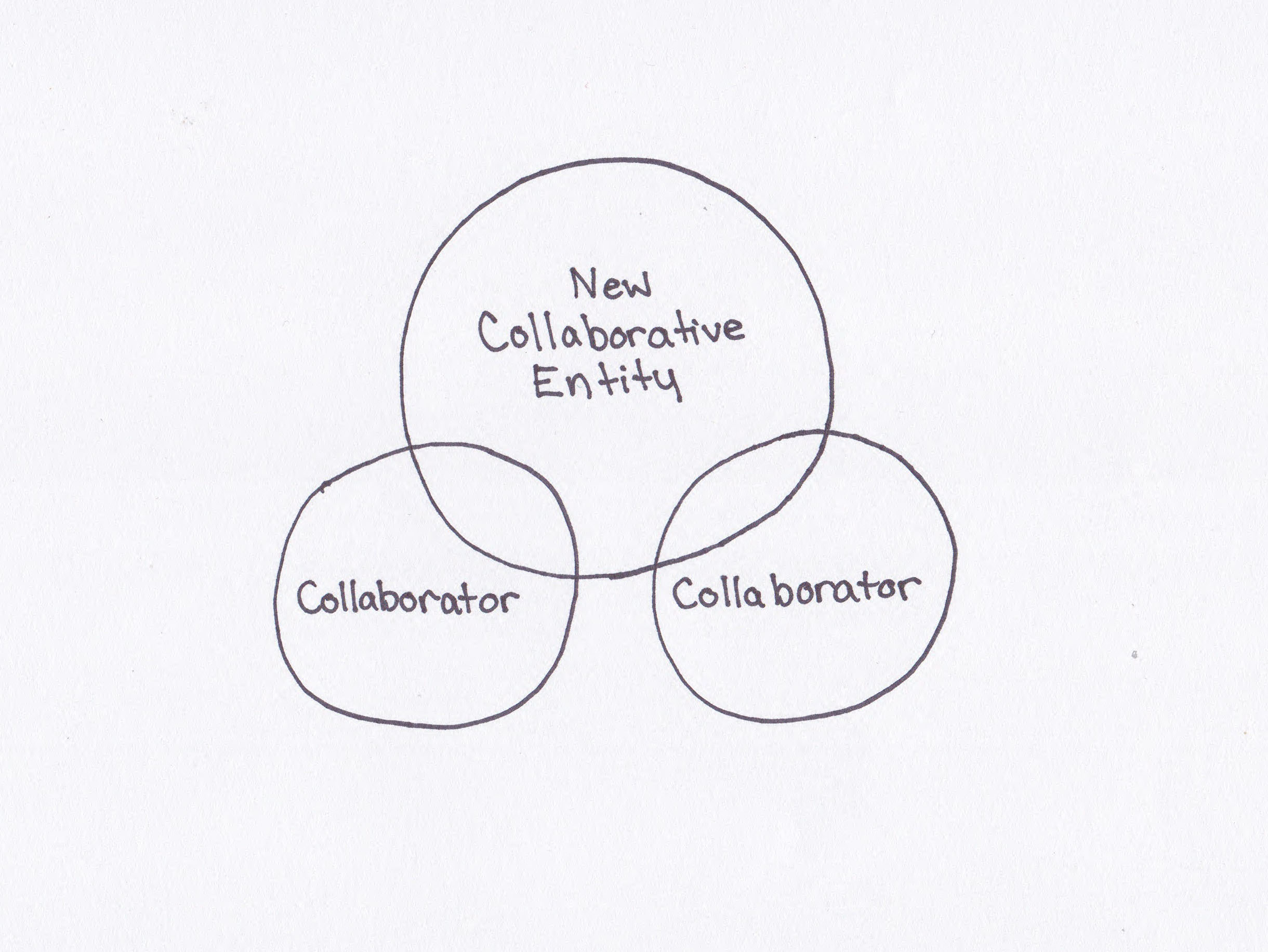

Once we are gathered, how do we build a new ethics of benevolence among us? In their article titled “Talking Cure: Dialogue as Collaborative Resistance,” researchers and performance artists Victoria Stanton and Stacey Cann reflect on dialogue and on collaboration as a slow artistic form. According to Stanton, a practical collaboration “means slowing down a process, being more thoughtful, taking more time, pushing against this culture of efficiency.”4 4 - Victoria Stanton and Stacey Cann, “Talking Cure: Dialogue as Collaborative Resistance,” Esse 104 (Winter 2022): 45. In other words, to begin a process of degrowth, it becomes imperative to move away from the productivist rationale. This desire for transformation also affords an opportunity to reaffirm our personal limits and those of others, among which I include all family commitments, disabilities, as well as any reduced availability and other limits deemed necessary. Let’s be clear: our benevolence should always take precedence over the administrative responsibilities listed on our contracts.

Some will say that the principle of “everyone for themselves” is inevitable, given our struggle for limited subsidies and grants. Can we collaborate while competing? This question motivated the creation of the Bureau of Non-competitive Research, a collective of artists and researchers co-founded by Stanton and Cann in 2021. By humorously playing on the idea of (non-)competition, their interventions underscore the absurdity of many administrative processes. Their ethics of collaboration, centred on reciprocity, “forces you to think about what you are doing and why you are doing it.”5 5 - Ibid., 46. I would add the following question to this introspection: with whom and how do we wish to collaborate to reimagine the arts sector?

Is Degrowth a Postpunk Movement?

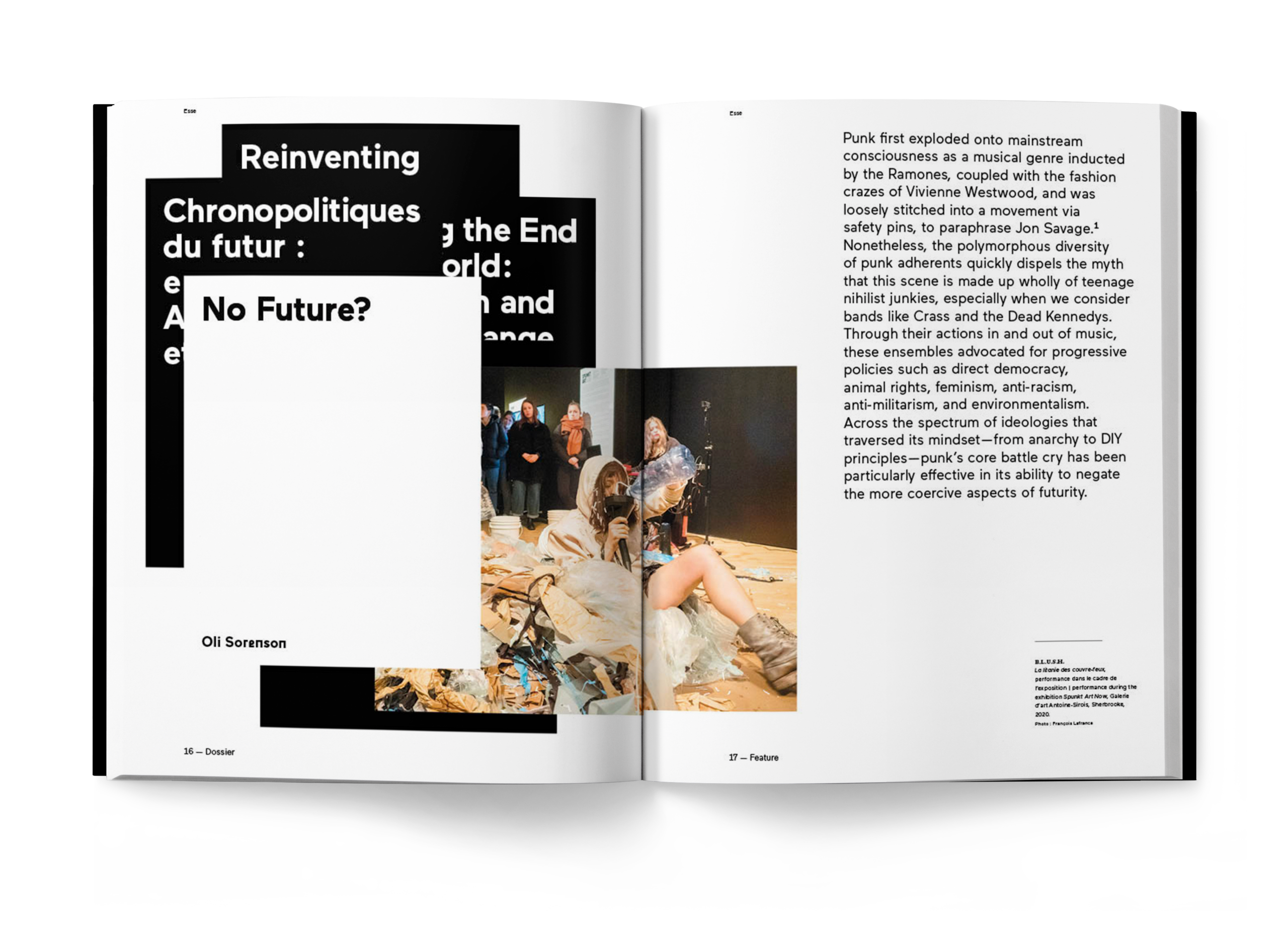

In a 2020 Esse article, “No Future?,” artist and researcher Oli Sorenson explored the impact of the punk movement on contemporary art. When I examine the ideals of anti-globalization and, more recently, of degrowth, it seems clear to me that the two movements share a postpunk spirit. On this topic, Sorenson explains that the punk rejection of a utilitarian approach to production and reproduction encourages individuals to focus on their potential for self-fulfilment, an idea similar to the model of wellbeing supported by degrowth.6 6 - Oli Sorenson, “No Future?,” Esse No. 100 (Fall 2020): 20, accessible online. This desire for personal accomplishment, says Sorenson, tends to distance itself from the futile hope of a “redemptive futurity”7 7 - Ibid. in which advanced technologies reduce our working hours. As such, it is pleasure, rather than capitalism’s glorified rate of return, that becomes the main indicator of wellbeing. The adoption of a postpunk ideology today might well indicate a tipping point regarding our collective and individual priorities, wellbeing becoming at once a driving force and a new collective ideal.

In his critique of “redemptive futurity,” Sorenson touches on another fundamental point: the contribution of technologies to our conceptions of the future. Technosolutionism is based on the belief that technological innovation will solve all our problems—what Sorenson terms “prophecy.” Yet, what the punk and degrowth movements have in common is a mistrust toward extractive technological innovations. For a great number of artists, this caution takes the form of a technocritical approach, as exemplified by Kanien’kehá:ka artist Skawennati and her cyberpunk avatars. Her interactive work The Peacemaker Returns (2017) is a futurist saga in which the Haudenosaunee people’s ancestral knowledge about peacemaking helps solve intergalactic conflicts. Skawennati does not give way to some illusory salvation but proposes, instead, a decolonialized and technological vision founded on the reconciliation of different temporalities and knowledge paradigms.

Anticapitalist Commons

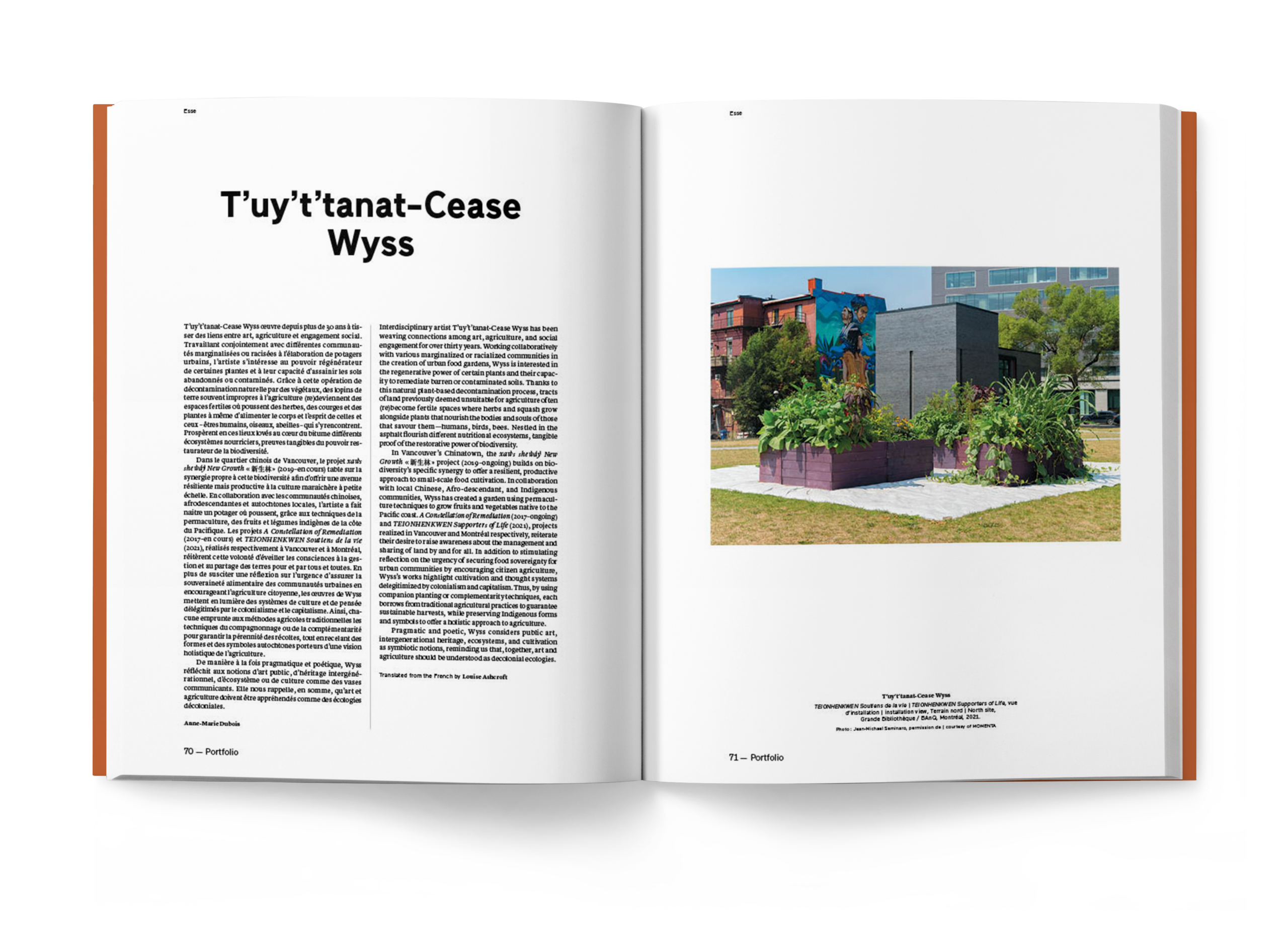

In degrowth literature, a large number of authors are interested in the role of the commons as a place of potential transformation. In the definition given by researcher and economist Bengi Akbulut, commons consist of spaces open to all, functioning outside the purview of both the state and the market, and facilitate production and reproduction through collective effort, equal access to resources, and democratic decision-making processes.8 8 - Bengi Akbulut, “Les communs comme stratégie de décroissance,” Nouveaux cahiers du socialisme, No. 21 (Winter 2019): 161, accessible online (our translation). Commons are generally understood to be areas of shared resources, both material (water, land, forests) and immaterial (knowledge, stories). There has recently been a surge in art projects related to the pooling of resources. In 2021, on the invitation of MOMENTA Biennale de l’image, artist T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss transformed the northern section of Montréal’s Grande Bibliothèque (BAnQ) into an urban garden. Titled TEIONHENKWEN Supporters of Life, this ephemeral project sought to mobilize ancestral agricultural knowledge, including through the cultivation of indigenous species adapted to the local climate. As Anne-Marie Dubois pointed out in her presentation of the artist, this project, which shares knowledge that was delegitimized by colonialism and capitalism, expressed a desire to democratize the management of lands and their shared use by one and all.9 9 - Anne-Marie Dubois, “T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss,” trans. Louise Ashcroft, Esse, No. 110 (Winter 2024): 70, accessible online. In this respect, public art can certainly play a decisive role in degrowth practices when engaged in critical reflection on land use.

In her research on contemporary commons, Akbulut also sheds light on bartering practices, a common form of exchange among artists and among institutions. Esse No. 49 (Fall 2003) was devoted to barter and included a text by artist and cultural worker Martin Dufrasne. Himself a fervent practitioner of exchange and collaboration in his work, Dufrasne considers that bartering brings out individual capacities often neglected by the capitalist system but fully recognized, and even valued, in the framework of a relational economy.10 10 - Martin Dufrasne, “Donnant-donnant,” Esse, No. 49 (Fall 2003), accessible online. In 2001, at Skol, Dufrasne presented his project Se refaire un salut, for which he made all his personal belongings available to members of the public, who were then free to take them in exchange for articles of similar value. Dufrasne explains that “the term value was understood in its broad sense and summoned symbolic, personal, and sentimental value in addition to the presumed market value.”11 11 - Ibid. (our translation). The project gave primacy to the emotional charge of the exchange, an approach similar to that of Stanton and Cann, whose collaboration is based on the importance of relational connections.

Blind Spots, Speculation, and Resistance

Adequate cultural funding should not only ensure the sustainability of our mandates but also allow for the creation of an experimental fringe. The term “degrowth,” lying midway between growth and post-growth, suggests in itself a transitional period of experimentation and risk-taking. It is time to say our farewells to the hyperproductive model and to take advantage of our creativity to consider alternatives to our working methods. Whether motivated by a collaborative or postpunk spirit or by a desire to favour bartering and the pooling of resources, degrowth is already a part of our cultural landscape. The propagation and interrelation of these efforts, as well as the study of their impact, will require time and—ironically—money! An important gap in existing research is the institutional dimension of degrowth. What would a “degrowing” institution look like? Is it even possible—or desirable—to institutionalize degrowth? In the absence of immediate answers, my wish is to see more media attention given to curatorial groups whose non-institutional methodologies open the way for experimentation and risk-taking.

Another blind spot in the debates around degrowth is equality of opportunity. An institution that would undertake a long-term and sustainable collaboration with a handful of artists would risk increasing competition in its calls for projects. Yet the pace of our current programming cannot go on; the all-too-short deadlines are incompatible with the necessity of caring practices. The status quo being what it is, it is through experimentation and radical actions that our successes and failures may contribute to the advancement of a planned and evolving degrowth.

Translated from the French by Ron Ross

Sophie Dubeau Chicoine is an emergent curator and researcher from Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montréal currently based in Tkaronto/Toronto. Her curatorial research is inspired by anti-capitalist visions, queer utopias and slow methodologies. Her writings have been published in Ex_situ and Esse arts + opinions. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Art History, Museology and Art Dissemination from UQAM and is pursuing a SHHRC-funded Master of Visual Studies in Curatorial Studies at the University of Toronto.

Links to the articles cited: Ariane Daoust & Aline Ginda Victoria Stanton & Stacey Cann Oli Sorenson Bengi Akbulut Anne-Marie Dubois Martin Dufrasne