Photo : courtesy of the artist & Gagosian Gallery

(Im)possible Bouquets

Fast-forward several hundred years and impossible bouquets reappear, more haunted, more troubled. Although modern transportation and communications technologies continue to compress time and space, it is globalization that has made impossible bouquets possible. The globalized cut-flower market has made these once-illusory arrangements an easily attainable reality. Nevertheless, artists continue to depict impossible bouquets of sorts, denoting how flora can lay bare the geopolitical realities of territorialization and the continued commodification of nature. The works of Taryn Simon and Yto Barrada reveal the complicated and ironic ways in which impossible bouquets are manifested in present-day contexts.

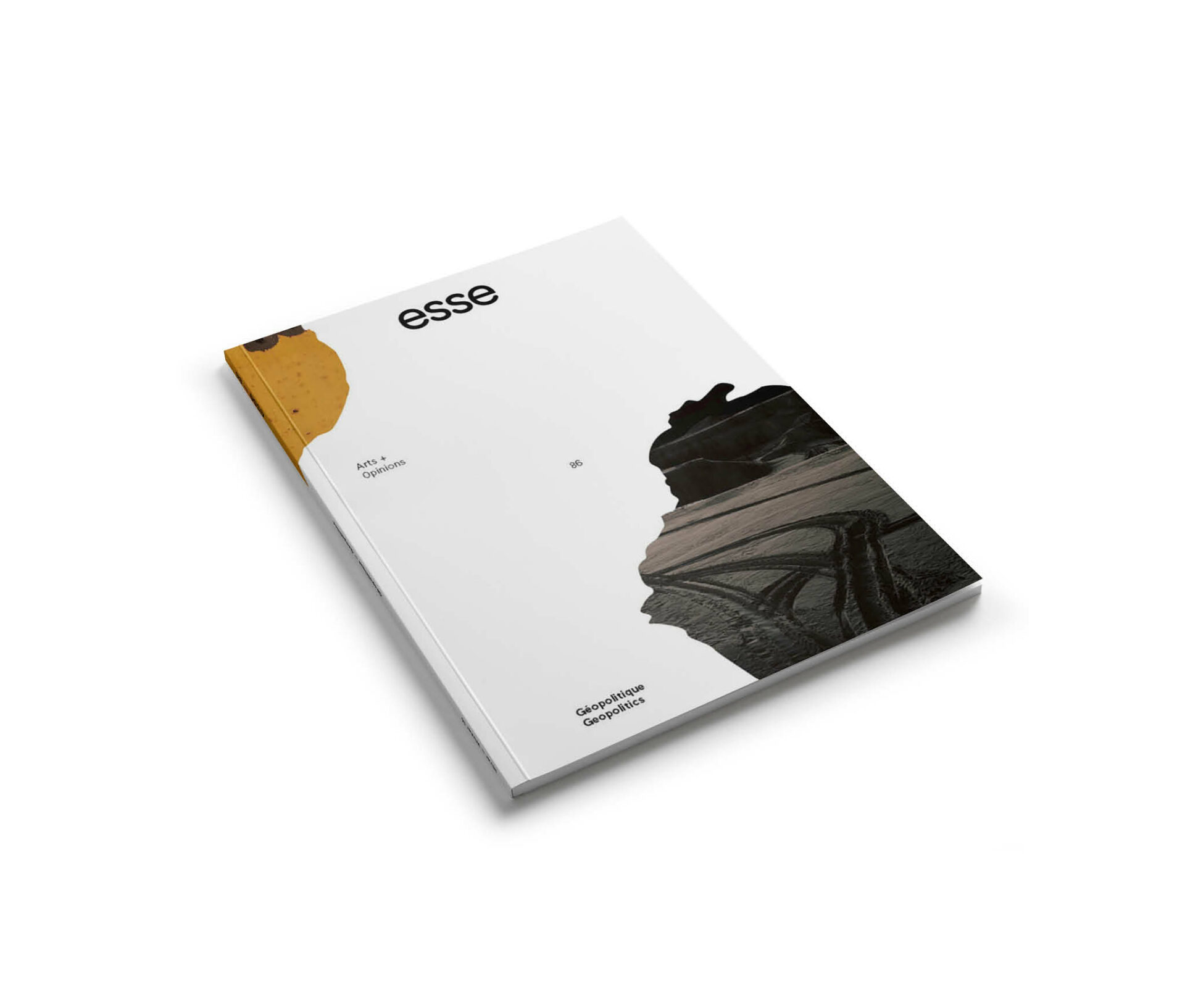

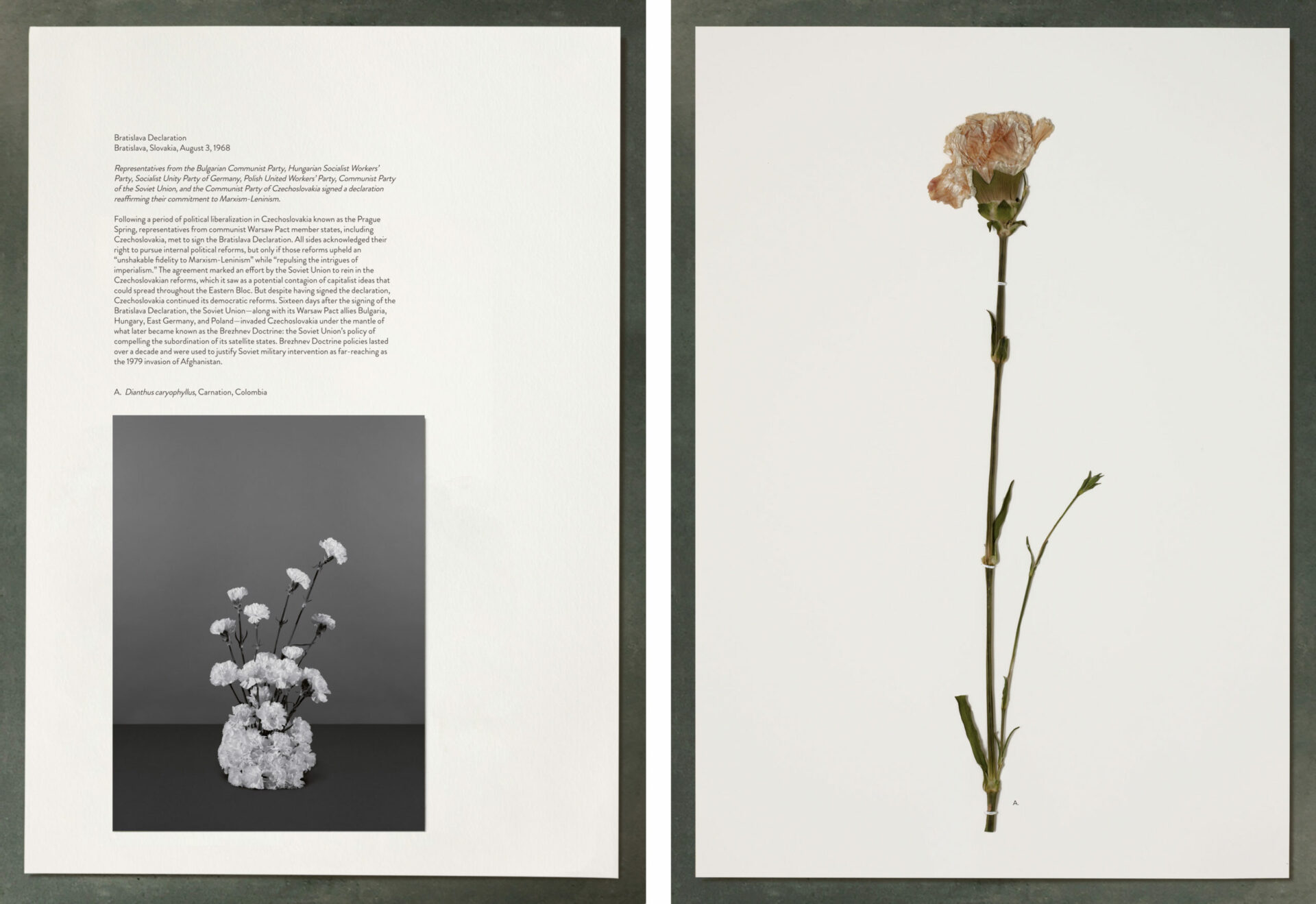

Exhibited at the Arsenale as part of the 2015 Venice Biennale, photographer Taryn Simon’s Paperwork, and the Will of Capital (2015) points to the oddly common occurrence of political dignitaries being posed and photographed with large floral arrangements when signing declarations, treaties, and contracts. In such instances, these blooms become anchored to the event, bearing witness to spheres of power, economic regulation, and the passing of international law. Perhaps as a means to acclimate and pacify the citizens on the receiving end of the statutes, the floral arrangements are folded into the aggrandizing tone of these official proceedings. As a way to make evident this convention, Simon reproduced and photographed the arrangements fashioned for specific signings, based on archival images of the ceremonies. The photographs are paired with the accompanying decree, marking historic events that realized new world orders, nations, and statutes that continue to influence contemporary politics. The bouquets reference the forty-four countries represented at the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, held in New Hampshire in 1944, a significant gathering that resulted in the establishment of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Bratislava Declaration. Bratislava, Slovakia, August 3, 1968 (left);

Dianthus carophyllus, Carnation, Colombia (right), detail, Paperwork, and the Will of Capital, 2015.

Photo : courtesy of the artist & Gagosian Gallery

The images of the arrangements and accompanying agreements are stacked in tome-like columns and enclosed in vertical vitrines. In the right stack are pressed specimens from each arrangement, serving as a catalogue of the over four thousand plant varieties that Simon had imported to her studio from Aalsmeer, the Netherlands, where the largest flower auction in the world is held. As stated in the didactic text introducing the installation, each arrangement represents an impossible bouquet. Due to globalization and advances in farming and shipping, impossible bouquets are no longer the stuff of fantasy. Like any other commodity within the globalized market, cut flowers are imported and redistributed from almost every part of the globe, ensuring that consumers have access to any desired flower type at any time of the year. Flowers grown in Colombia, for example, are bred in Dutch labs and sold at Dutch auctions to internationally entangled retailers and distributers. Catherine S. Dolan notes, “While the flower industry has flourished through market liberalization, deregulation, and corporate consolidation, it has also become a trope for globalization gone awry, one that bears the familiar social imprimatur of economic neoliberalism.”1 1 - Catherine S. Dolan, “Arbitrating Risk through Moral Values,” in Hidden Hands in the Market: Ethnographies of Fair Trade, Ethical Consumption, and Corporate Social Responsibility, ed. Peter Luetchford, Geert De Neve, Jeffery Pratt, Donald Wood (Bradford, UK: Emerald Publishing Group, 2008), 277. An often-cited example of this is Kenya’s thriving flower market, which was essentially nonexistent before the 1990s.2 2 - Michael Blowfield and Alan Murray, Corporate Responsibility (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 100. Although Kenya annually exports over $100 million in botanical goods to Europe, this specific asset market is responsible for environmental degradation, endangering and exploiting workers, and destroying local communities.3 3 - Ibid. The same pattern has befallen the flower industry in Bogotá, Colombia. Colombia is the second-largest exporter of cut flowers (after Holland), with greenhouses generating $600 million in annual export earnings.4 4 - Kevin Watkins, “Deadly Blooms,” The Guardian (August 29, 2001), http://www.theguardian.com/society/2001/aug/29/guardiansocietysupplement5. Botanical-based earnings are, however, coupled with: hazardous working conditions, in which employees are required to handle highly toxic chemicals; and environmental devastation, whereby contaminants from pesticides banned elsewhere have been found in groundwater.5 5 - Ibid. These are some of the by-products of impossible bouquets in the twenty-first century.

In some ways, Simon’s bouquets seem emptied. Her gesture, however, is not a hollow one. Solitary arrangements posed with colourful backgrounds may, at first glance, seem to amount to nothing more than aesthetically resolved compositions, devoid of urgency and agency. No longer flanking important men in their march toward economic and political domination, the flowers are ostensibly stripped of any pageantry. Instead, the floral arrangements testify that the accompanying documents likewise operate as impossible bouquets, evincing man-made fantasies of fluid borders, markets, and cultures that can be manipulated and redrawn at will. Simon’s installation evokes a globalized empire governed by the few but influencing the many. The flora of this territory belongs solely to the histrionics of power — to how it is sustained, marketed, performed.

Palm Sign, 2010, installation view, Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beyrouth, 2009.

Photo : courtesy of Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beyrouth & Hambourg

In contrast to Simon’s Paperwork, and the Will of Capital, Moroccan artist Yto Barrada’s film Beau Geste (2009) focuses on the immediacy of a single action. The film documents the effort of several individuals to save the roots of a lone, ailing palm tree. This attempt to prop up the tree was organized by the artist, whose voice-over clarifies the desire to undertake such a precarious activity that will likely fail. Her even-toned narration tells us of rapid gentrification spreading across Morocco, including in her hometown of Tangier. Hamza Walker eloquently describes the artist’s approach to changing landscapes this way: “The boom and bust cycles of development featured in Barrada’s images of forgotten foundations, sporadic patterns of exurban construction, and shanties juxtaposed against high rises are set against the languor of napping indigents, colonial ruins and portraits of daydreamers.”6 6 - Hamza Walker, “On the photographs of Yto Barrada,” Prefix Photo 16, no. 1 (2015): 48. We see this clearly in Beau Geste, which also filmically stresses that “modernization” enterprises ensure that vacant plots of land are quickly subsumed by urbanization. Due to its protected status, a palm tree can halt development, and this particular one has been purposefully impaired so that it will rot and eventually die, allowing the landowner to develop the site. The single tree becomes a bastion against urban sprawl as its protectors undertake a small act of resistance against the inevitable encroachment of urbanization. The almost comical effort to create a support system for the tree relays a tension among communities, developers, and the delicate growth that buttresses the built environment. It is a narrow gesture that nonetheless raises essential questions about a global condition of ecological destruction in the face of urban expansion and the homogenization of communities under pressure from gentrification.

Beau Geste, video stills, 2009.

Photos : courtesy of the artist & Sfeir-Semler Gallery, Beirut & Hamburg

This is not the only palm tree that has occupied Barrada’s practice. Palm Sign (2010), a large painted-metal sculpture dotted with coloured light bulbs, further expresses the artist’s concern with rampant development in Morocco. The palm tree is a deeply embedded symbol of local “exoticism” — one that, like Simon’s florals, has been commodified by particular interest groups, including developers and hotel chains. Barrada’s focus on the palm, in this and other works, reveals the tree’s use in various marketing and promotional campaigns.7 7 - Kyla McDonald, “Palm Sign,” http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/barrada-palm-sign-t13281/text-summary. But while this emblem has been used to sell a particular image of Morocco to tourists and investors, it is also an impossible bouquet of sorts. Ironically, the palm tree, with all its promises of consumable “paradise” and “oasis” in the form of new resorts and golf courses, is not native to Morocco and was in fact imported into the region.8 8 - Ibid. Palm Sign, like its organic counterpart in Beau Geste, holds in its characteristically pendulous crown its contradictions as an icon. The marquee-like sign seems to promote a shimmering Morocco of tomorrow, but its faded and scratched surface soon undermines it, alluding to a kind of false advertising or, rather, a confession that “modernization” processes so often benefit only a select few. In an interview with Charlotte Collins for Open Democracy, Barrada explains, “The announced goal for Morocco for 2010 is to have ten million tourists come to the country — that’s a one-way street! Everyone’s coming over — guess what? We can’t move! Legally, nobody can get out of the country — ‘nobody’ meaning a big, big majority.”9 9 - Yto Barrada and Charlotte Collins, “Morocco Unbound: An Interview with Yto Barrada” (May 17, 2006) https://www.opendemocracy.net/arts-photography/barrada_3551.jsp. Like an impossible bouquet, Barrada’s sign draws together conditions that might not naturally co-exist, or at least suggests that these conditions of old/new and local/global might not co-exist with the quixotic ease in which they are so commonly advertised.

Simon’s and Barrada’s use of flora speaks to broader socio-political impulses to reimagine borders and reallocate spaces. This flora further discloses how the natural world has been usurped by the power mechanisms that too freely redefine our notions of place. Both artists ask that we see the trees for the forest, that we take an expanded view of how the biotic has been used in the service of the manufactured. It might not be the most scenic view, but it is a necessary one.