photo : Guy L’Heureux, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Shedding the animal imagery for which she was generally known,1 1 - Recall, for instance, her exhibition “Vivarium,” at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (October 21, 2004, to March 13, 2005), which brought together a collection of paintings that staged — or caged — an entire population of animals — tiger, elephant, wild dog — seemingly drawn from Indian wildlife. Montreal artist Christine Major has been working on a series of paintings since 2011 under the title Crash Theory. The iconography in this project draws from images of calamity — car crashes, Amelia Earhart’s disappearance, the collapse of the Twin Towers in New York, among others — culled from libraries, archives, the Web, and other artworks. The title of the project had first been given to a much earlier painting, a large triptych presented in an exhibition titled Terreurs intimes (2000).2 2 - “Terreurs intimes,” a solo exhibition presented in 2000 at contemporary gallery Axeneo 7 in Hull, Quebec, and at La Centrale Galerie Powerhouse, in Montreal, Quebec. In nascent or variously explicit form, sensually imbued desublimation and disorder were already in evidence in the artist’s work of the last ten years. The tension between body and chaos had also been more frankly explored in the recent exhibition Ninfa morderna (2010),3 3 - “Ninfa moderna,” solo exhibition presented in 2010, at Galerie Donald Browne, in Montreal, Quebec. which staged the slumped, debased bodies of young women in ramshackle settings inspired by the violence surrounding the Jaycee-Lee Dugard case. Here, the disorder conjured a perverse eroticism.

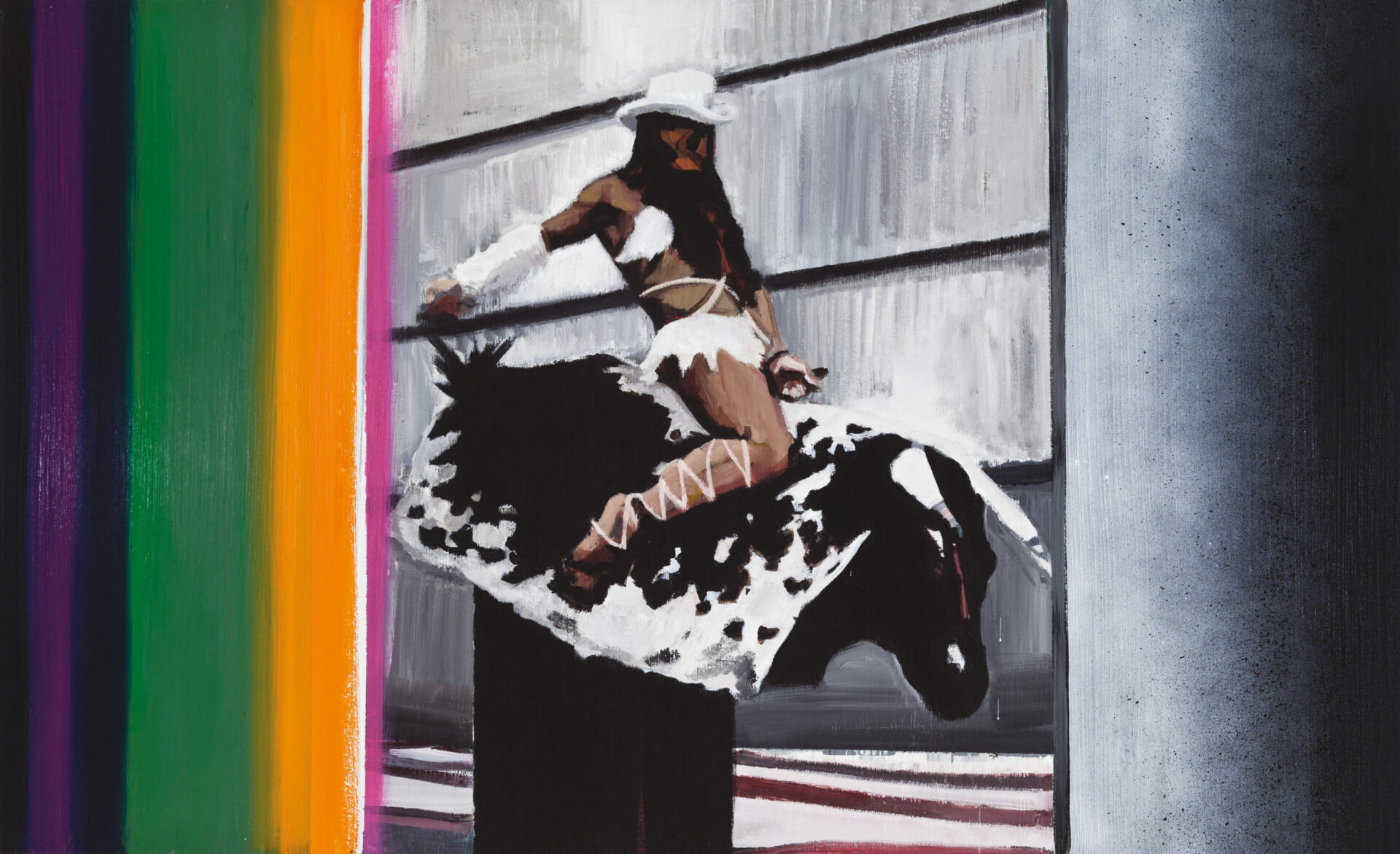

Crash Theory pursues the exploration on the same emotional register. From a thematic point of view, one can thus situate the series in an exploratory continuum from the relative eroticization of anxiety (Terreurs intimes, 2000) to the sense of alienation and isolation in Vivarium (2004), and carrying on with the dialectic between degradation and survival in Ninfa moderna (2010).4 4 - This title is taken from Georges Didi-Huberman’s Ninfa moderna: Essai sur le drapé tombé (Paris: Gallimard, 2002), from which the artist’s debasement-survival theme likely derives. Crash Theory incorporates reminiscences of the broken, disengaged bodies, fetishized and obscenely suspended in their resistance, that populate “Ninfa moderna.” Except that here the collisions, the clutter, the scrapyards are juxtaposed with the kinds of recreational sports activities that habitually sexualize women’s bodies: pom-pom girls and cow girls accompany tragic scenes of traffic accidents. In popular cinematic culture, the cheerleader and cow girl are generally associated with clichés of superficial, hypersexualized women. As such, the juxtaposition of car crashes and clichéd images of women may certainly be interpreted as an attempt to call attention to the bankruptcy of such images on a human level. It seems to me, however, that a feminist reading focused on the subversion of male car/woman fantasies cannot fully exhaust the significance of these paintings.

de la série | from the series Crash Theory, 2011.

photo : Guy L’Heureux, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

On a narrative as much as a formal level, there resides a profound ambiguity in Crash Theory. Juxtapositions of somewhat abstract, highly gestural areas with more polished, figurative ones, together with the layering of source images transform the painting into a kind of palimpsest, its narrative remaining enigmatic, only half-articulated. A palpable, emotional tension ensues (as reflected in the impasto treatment). By not immediately revealing everything, Crash Theory functions somewhat like desire, this anticipatory state of ever-deferred pleasure.

In terms of form and composition, I can’t help point out some unintentional affinities between Dissociations and the formal strategies that Degas employed in his late 1890s pastels representing dancers in the wings. One unexpectedly finds in Les meneuses de claque the anonymous faces, contorted postures, promiscuous bodies, energetic and gauzy frous-frous (or pom-poms), and vaguely-delineated confined spaces that surround Degas’s dancers. In Degas, all these elements — the vagueness (which some have interpreted as a tendency toward abstraction), the anonymity, the hard-to-define postures — make the representation deliberately ambiguous, and the power relationship equivocal, as it oscillates between attraction and repulsion, between objectivising and individuating the dancers.5 5 - Richard Kendall, “Signs and non-Signs: Degas’ Changing Strategies of Representation,” in Dealing with Degas: Representations of Women and the Politics of Vision, edited by Richard Kendall and Griselda Pollock (London: Pandora Press, 1998 [1992]), 198. What are the specificities of such effects in Crash Theory?

de la série | from the series Crash Theory, 2011.

photo : Guy L’Heureux, permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

I would like to suggest that these zones of ambiguity — the untellable story, the veiled (or restrained) violence — suggest an ambivalent sensibility, a situation that mingles feelings of anxiety and rapture, “the uncanny” (das Unheilmliche) that Freud spoke of.6 6 - Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny” (Das Unheilmliche), first published in Imago, Vol V, 1919. For Freud, the concept of the uncanny serves to describe the tension between temptation and horror, between desire and fear, resulting from a process of interiorizing initially disturbing images (here, images from the media and popular culture) that have become familiar. In the case before us, the uncanny emerges from a particular eroticization of horror, a rather troubling relationship between the body and the mechanical smash-up. The juxtaposition of sexualized figures and scenes of collision amid heaps of refuse provokes a discomfort that does in fact recall — in a more restrained fashion, I admit — the mood of David Cronenberg’s controversial film, Crash.7 7 - Crash. Directed by David Cronenberg. Canada/UK: Alliance Communications Corporation/The Movie Network/Telefilm Canada/British Recorded Picture Company, 1996. Exploring the relationship between sexuality and the machine, a favoured theme of Futurist Filippo Marinetti, Cronenberg stages marginal characters who fetishize car crashes and for whom pleasure is inseparable from pain, sex from death. The underlying subject of Cronenberg’s film, however, is the transformation of the body through a dehumanizing technological society where sexuality, conceived as pure pleasure, a sex drive detached from any emotion, morality, or norm, is only possible through extreme, destructive experiences. Certainly, the raw realism of Cronenberg’s film has nothing to do with Major’s suggestive proposal. Nonetheless, like Cronenberg’s Crash, Crash Theory stages the relationship human beings have with their bodies in the age of machines and, I would add, in the reigning age of the image — for Crash Theory is the result of an accumulation of images and examines our vision of the body in its rapport with the machine, ultimately defined by and as image.