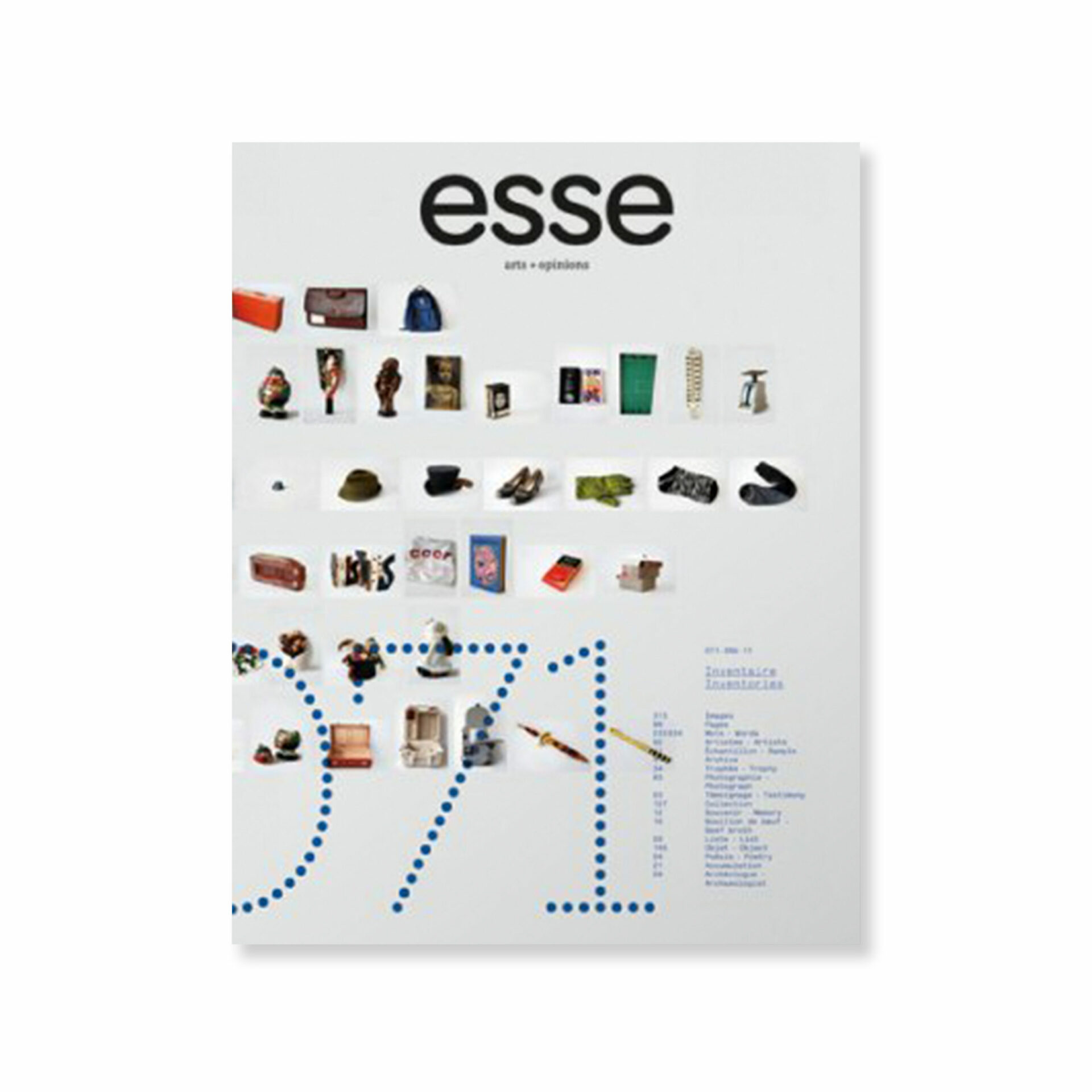

photo : permission de l'artiste | courtesy of the artist

“In her dream she made an inventory of all the times her father had photographed her on the sly without her being immediately aware of it. All the memories were coming back. Photographs in which she is all by herself, and others with Moira. She had to note everything quickly, failing which she would forget and would have to wait for her brain to once again grant her access to this exclusive memory domain during another night of insomnia.”1 1 - Laia Fàbregas, La fille aux neuf doigts, translated into French from the Dutch by Arlette Ounanian (Arles: Actes Sud, 2010), 73. In the novel La fille aux neuf doigts, Laia Fàbregas describes the quest of two sisters, Laura and Moira, who have been marked by a singular family practice: forbidding any use of a camera. Their parents taught them the art of taking mental pictures and of writing their impressions down on the white pages of a photo album. But now in their thirties the two sisters feel increasingly troubled, as though a part of their past was missing inside of them. Still holding on to the hope that the pictures taken unbeknownst to them exist, they begin searching for traces of their presence in the archives of the local press.

This work of fiction directly echoes a basic thesis that informs the entire work of the French philosopher Pierre-Damien Huyghe, for whom “lived experience no longer exists without a recording.”2 2 - Pierre-Damien Huyghe, L’art au temps des appareils (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2005) and Faire Place (expanded new edition) (Paris: Les éditions Mix, 2009). The reader can also consult the three seminars dedicated to “forms of consciousness in the age of reproduction,” given by Pierre-Damien Huyghe in 2006 at the Maison Populaire de Montreuil, France: www.maisonpop.net/spip.php?article572. Drawing on Walter Benjamin, this thesis describes a world which has lost its centre of gravity and in which photography and other technological inventions must no longer be considered as simple capturing or viewing tools, but as recording devices: they make it possible to fix, conserve and eventually reproduce sounds, images and data. Also, for Huyghe, it is our entire life and our experience of it, far more than our relationship to images, that is shaken up: “the ancestral experience of the here and now is expanded by the more modern one of the here and there.” Lived experienced can no longer be synthesized; it is scattered because it is immediately recorded, and hence potentially communicable. For Huyghe the philosopher’s task is therefore to rethink the altered operating mode of the subject, whose henceforth technologically assisted perception disrupts ways of being, thinking and behaving.

In the era of everyday technologies and pervasive computing, the smartphone has become an indispensable accessory primarily due to its being equipped with extraordinary photographic and video recording capacities. Amateur photography is no longer a restricted practice exclusively tied to family events (births, marriages, holidays), but a sort of attribute of the subject, a gesture whereby to automatically capture a moment one deems pleasant. It seems very suspect, even abnormal, nowadays to not think of taking a photograph or making a short video during moments of joy and plenty. Automated collection and inventory procedures are emerging as dominant aesthetic forms; displayed on the surface of file sharing service web pages, these functions structure our sensibility and organize our thinking. They generate congenial forms — galleries, reading lists — in which photographs and videos coexist, both autonomously and in relationship to one another. From a metaphysical point of view, this world of data could resemble that of atoms described by Lucretius in De rerum natura; its clinamen — as a principle of encounter — would be the visitor measurement and traffic increaser programs developed by a few unscrupulous engineers who work for companies that have turned amateur practices into a commodity like any other.3 3 - For example Flickr’s “interestingness.”

Automatically generated collections and inventories are contributing to three major cultural phenomena. The first concerns the very character of a sensibility that is marked by exposure to poor and volatile forms, low quality sounds and images which can circulate or be rapidly reproduced. While software makes it possible to manipulate, improve and even build images with decreasing cost, well-thought-out images are actually lacking: bad pictures and photographs proliferate on the databases generated in personal computers. The second phenomenon regards the proliferation of pornographic images: the uploading of this data reveals the astounding photographic and video activity of couples who film their sexual acts. If the philosopher Charles Lalo analyzed the link between beauty and the sexual instinct in the 1920s,4 4 - Charles Lalo, La beauté et l’instinct sexuel (Paris: Flammarion, 1922). nowadays it seems to be accepted that to film one’s lovemaking, barring the porn industry, is a key experience of intimacy. The third major phenomenon relates to the fact that in these anesthetic and style-less worlds it is well regarded to mix genres and talk of aesthetic practices and artistic experiences. This is a central point that is far from being a rhetorical artifice or a conceptual affectation.

Clôde Coulpier, Ma soeur, mes cousines et leurs amies.

photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

In fact, the detailed observation of the use of everyday technologies and the web teaches us that to take a picture or record a video sequence is to manifest a sensibility created by recording instruments themselves, which must be seen, on a conceptual level and in light of Walter Benjamin, as instruments of perception. Systematically held away from the eyes, the image recording device associates the gesture of amateur photography with the test, with the aesthetic experience. It is henceforth about accomplishing the automatic destiny of images by recording a sequence at arm’s reach, all the while striking sometimes physically extreme postures in order to adjust one’s presence in the image frame.

On the other end of the spectrum, video and photo file sharing services multiply the unlikely encounters between people with no prior affinities and thereby promote cultural misunderstandings: as soon as a person goes on the web s/he exposes him or herself without precaution or vigilance to difficult-to-grasp forms of extimacy and inevitably comes up against the inoperativeness of art’s modelling and anticipatory functions.5 5 - I am here referring to the aesthetic theory developed by Alain Roger for whom “art has a fourfold function: distortion, condensation, modelling and anticipation,” in Art et anticipation (Paris: Les éditions Carré, 1997), 9. I am also referring the reader back to my article “Le modèle artistique n’est plus une référence,” esse, no. 58, Extimité issue (2006). Being without apparent quality, such productions disconcert aesthetic judgment and lead art theories towards uncertain and scattered practices. Despite this, the observation of practices linked to visiting file sharing websites reveals a web surfer attitude that has not received attention until now: whatever the circumstances, s/he is in a position of being a witness, if not the main one, of actions and experiences that are unfolding. In other words, s/he becomes the guardian of experiences. At once touched and stunned, because s/he conceptually gropes about in an attempt to identify what catches his or her gaze, and performs quasi-automatic gestures: adding a bookmark for the website in question, selecting images on a whim or for memory’s sake, or simply to have them available…. In the long run, with a little hindsight, the web surfer can no longer make out the difference between his or her personal files and, for example, the pages of a book by Hans-Peter Feldman (Voyeur, 2006) or the series of photographs by Anita Leisz (Are those your relatives? 2002). S/he becomes aware of having unwittingly engaged in artistic experiences; and this is without any formal creative aim or autobiographic project.

It is legitimate, in this context, to question the nature of an art form that corresponds to a time when it seems that lived experience no longer exists without a recording. One may be tempted to turn to artists who follow in the lineage of Elke Krystufek, Richard Billingham, Nan Goldin or Jun Yang. But this approach would be strictly analogical and comparative: it would be based on the distinction between the naïve use of images with an everyday and intimate tinge, and another of a more sophisticated and technical sort that falls within the field of art and its aesthetic games. And yet, as we stated above, the modelling and anticipatory functions of art are in a state of crisis.But, faced with the proliferation of amateur productions, there remains an operative function of art that consists of distorting. This applies to a series of photographs titled Ma sœur, mes cousines et leurs amies (My Sister, My Cousins and Their Friends) exhibited for the first time in 2007 by Clôde Coulpier at the Centre d’art Oui in Grenoble, (France). These are ordinary photographs taken by young teenage girls showing themselves in front of their friends: images of girls clowning around, which up until now had their place in diaries, secret boxes or on the walls of their rooms. Having found these images on an adult site, Coulpier puts forth the hypothesis that they came from personal blogs and that they were diverted and pirated by the porn industry. Plausible, though unverifiable. In calling this series Ma sœur, mes cousines et leurs amies the artist seeks to express the manner in which the network contributes to a sort of disorientation: “With the web when you look at photographs you begin with family pictures, then those of friends, followed by those of friends of friends, and still others, up to pictures of people you don’t know at all. The images circulate, travel and are recuperated, but one no longer knows where they come from and who is who.”6 6 - Personal interview with the artist. Once they are collected and selected, these images are developed at a discount store in 4 x 6 format and are then randomly redistributed in the exhibition space, mounted on the wall using stickers depicting cartoon characters. Strangely paradoxical, the distortion function of art thus consists of artificially replacing these uprooted images in their natural ecosystem — wall space — and of reinscribing them with a decorative function.

Coulpier’s low-tech visual operation appears almost counterpro-ductive in relation to the context of collecting and inventorying which today are the sensible foundation of our ways of being, thinking, behaving and creating. Nevertheless, the work shows how, in the face of the network’s incommensurable content and profuse amateur practices, we seem to have no trouble coming to terms with technology; how we almost ontologically manage to integrate it into our emotional life; how in a naïve and credulous way we entrust it to look after us, i.e., to record who we are, what we have been, what we have been for the gaze of others but never for ourselves…. And to do so both immediately and in a deferred way. These amateur practices are a response to the increased recording capacities of machines. They are the result of feelings which Charles Lalo has termed accessory feelings — feelings which are “only accompaniments to aesthetic thought, which may have a very important place within the whole of our existence, but which are neither the causes nor the effects of our contemplation of the beautiful: they are simply associated with it.”7 7 - Charles Lalo, Les sentiments esthétiques (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1910), 161. Having no aesthetic quality, these shared feelings are something we encounter in every moment of our lives: they are joy, pain, anger, love. And it is certainly the images of these feelings that are lacking for Laura and Moira, the two sisters of the novel by Laia Fàbregas.

[Translated from the French by Bernard Schütze]