Plein sud, Longueuil 2022.

Photo: Simon Belleau, courtesy of the artist, Plein sud, Longueuil, & Cooper Cole, Toronto

Becoming Free and Modelling the Possible with Rage and Humour

An Interview with Nathalie Batraville

I’m fascinated by the richness of her work and wanted to speak with her about how art, theoretical thought, and creation can contribute to ways of being and of imagining not beholden to hegemonic discourses and norms. As I have reservations about the notion of resilience, which, in my view, individualizes trauma and puts undue stress on victims of systemic oppression, I wanted to guide the discussion toward how creation helps to develop collective spaces open to encounters, mutual aid, empowerment, and lifting each other up.

Ariane De Blois : We met at Eve Tagny’s recent exhibition Funeral Garden, at Plein sud, for which I was the curator. Moved by the disproportionate effects of police violence afflicting Black, racialized, and Indigenous people and communities, Tagny wanted to offer a sympathetic, poetic space to encourage meditation, healing, and imagination. Although you and she work in different spheres, you share some affinities and concerns. Before asking you about your professional activities, I’m curious to know how you see literature and the arts as contributing to the development of your thought, your critical position, and, more generally, your sense of belonging to various communities of ideas and affects.

Nathalie Batraville : Art and literature provide the possibility of sustaining a connection with Black imaginaries, with critique, and with work that bears witness to and celebrates Black life. I am inspired by the interplay of these three modalities of discourse: one that speaks to how things are and have been; one that speaks to how things could be, with or without regard for what they can be within the confines of reason; and, finally, one that decodes hegemonic discourses in order to speak to how things ought to be. To the extent that I can choose the conversations in which I want to engage, these are the ones that I seek and that nourish me. Christina Sharpe’s conceptualization of “wake work” presents another modality of discourse, one for mourning the way things are and have been, a way to defend the dead, and a way to attend to the afterlives of slavery, to the traces and material effects of a past that is not yet past. Eve Tagny’s work beautifully created a space for mourning and witnessing, a space for collective grief and for reckoning.

I am also inspired by the way Fred Moten and Stefano Harney approach the idea of “study,” in their book The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study, as the sociality of those too unruly and undisciplined to be embraced by the university. Moten writes that study is “what you do with other people. It’s talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three, held under the name of speculative practice1 1 - Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013), 110, accessible online..”

Funeral Garden, exhibition view,

Plein sud, Longueuil 2022.

Photo: Simon Belleau, courtesy of the artist, Plein sud, Longueuil, & Cooper Cole, Toronto

I like to think of art and text within this capacious understanding of creativity and invention. This speculative practice also consists of, pressingly, mutual aid, direct action, and solidarity with incarcerated people. I am also drawn to pleasure and to beauty; I want to feel hitherto unimagined possibilities in my body. In the hands of Black subjects, literature and art can challenge the forms of structural violence that disallow and constrain touch, connection, and kinship for and between Black people.

ADB : How the three modes of discourse (historical, speculative, and decryptive) that interest you are intertwined is brilliantly articulated, it seems to me, in the thought of theoritician and Afro-feminist activist bell hooks. In one of your virtual lectures and one of your essays about her work,2 2 - Nathalie Batraville and Fania Noël, “Comment transformer radicalement la société avec bell hooks,” AyiboPost, December 17, 2021, accessible online; Nathalie Batraville, “(What is) Family?,” International Women’s Week, Vanier College, Saint-Laurent, Québec, YouTube, accessible online. you evoke her suggestion — both gentle and very radical from an epistemic point of view — that love is an action rather than an emotion, which is how we generally tend to look at it. Through this prism, do you think that we can envisage intellectual research, or even art practice, as being motivated by love?

NB : bell hooks approached love as a practice and an object of inquiry, making use of a Black feminist lens that constructs the political in relation to kinship, family, and community, as well as in relation to the state. This framework is grounded in collective liberation as opposed to notions of rights, equality, or empowerment. She defines love as that which nurtures the spirit and allows for growth.3 3 - bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions (New York: Harper Collins, 2001) Such a conception of love can be misleading as it may seem conciliatory or nonconfrontational; however, hooks’s work was anything but consensual. Rage can be an expression of love. I found it interesting during the last provincial election in Québec that the heads of the major parties, who were receiving death threats at the time, were conflating violence and rage and calling for an evacuation of rage from public discourse. Yet at times, rage is the only politically sound discourse — rage is an expression of lucidity, and an expression of love. There are so many reasons to be enraged.

Both art and politics can mobilize love through rage to challenge normalization of and desensitization to the various kinds of violence to which the state subjects Indigenous and Black subjects.

Locating and building on the intersections of art and politics, and of the intimate and the political, is what animates a lot of my work. I have been reflecting on touch recently, and on the way that various kinds of violence to which the state subjects Indigenous and Black subjects create unequal access to touch: capitalist labour exploitation, environmental destruction, policing and prisons, ableism, white supremacy, and fatphobia, to name a few. Not only do these structures foreclose and limit touch for certain subjects, they also produce coercive, extractive logics that can shape the kind of touch one might give and receive.

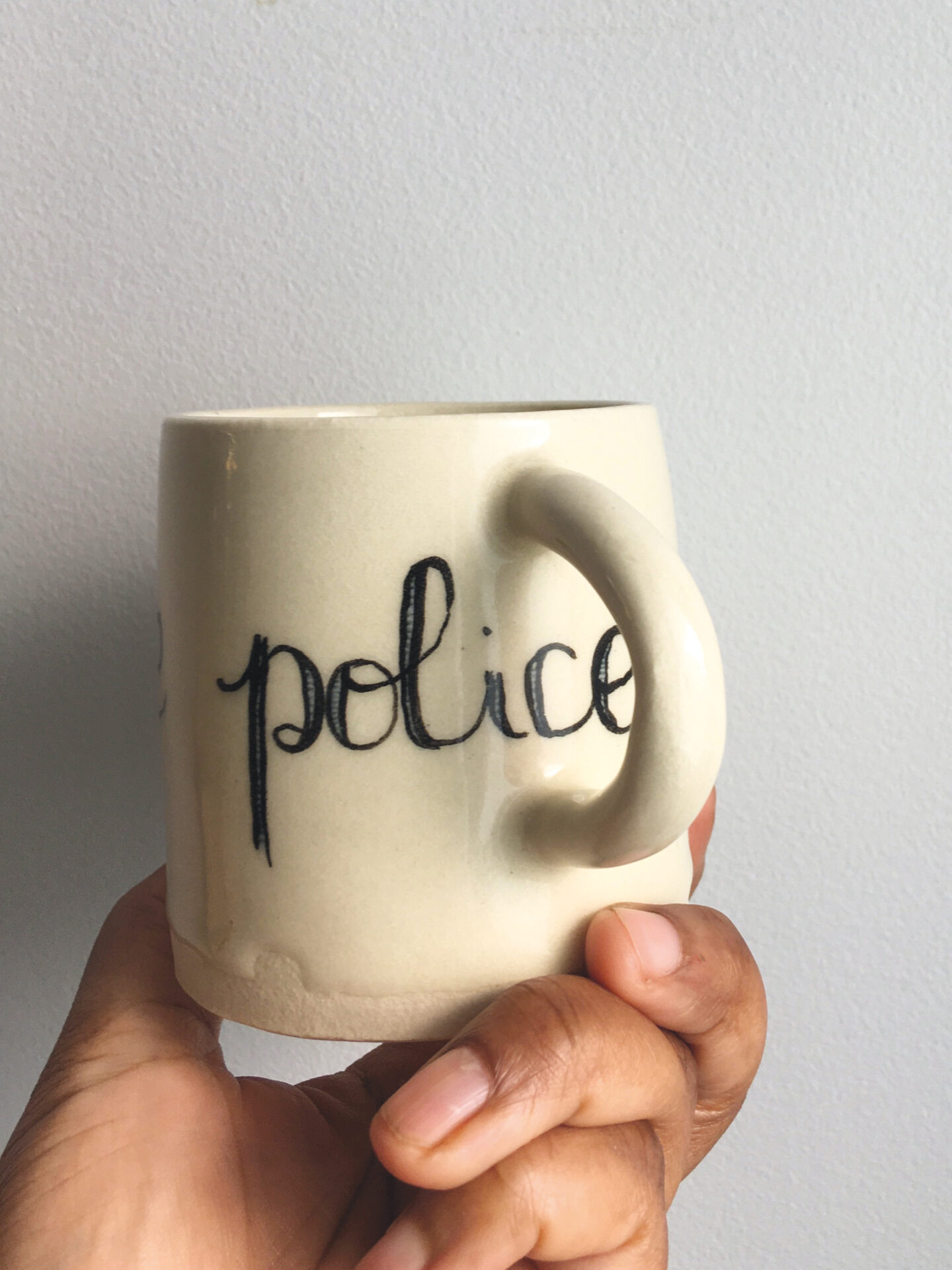

Stoneware mug, 2022.

Photos: courtesy of the artist

ADB : Indeed, bell hooks didn’t seek consensus in her work, and I think that’s what enabled her to follow such bold avenues for thought in education, family, romantic relations, and feminist issues. You’re currently working on a book titled Disruptive Agency: Towards a Black Feminist Anarchism, in which you reframe the notion of consent. Can you talk generally about your project and what issues you hope it will raise?

NB : My book builds on the work of radical feminists writing in the 1980s and 1990s who articulated critiques of consent by demonstrating the extent to which coercion and dependence overdetermine our choices, thus calling into question the meaning of agency and its usefulness as a concept. I offer the concept of disruptive agency to articulate ways of challenging the structures and logics of coercion that render the will, desires, consent, and agency of certain subjects irrelevant. I engage with Black women’s visual art, literature, and theory to explore what agency looks like as an everyday practice of attunement, negotiation, insovereignty, accountability, and civil disobedience. In thinking with these texts, I locate practices of disruptive agency in BDSM, plant care, Black and Indigenous solidarity, and prison abolition, and I reflect on the ways that these practices can embody modalities of love as defined by bell hooks.

ADB : When I read your work, I notice that it is motivated by the same impetus that you bring to all of your activities, in that there are many intersections between one field and another. For instance, I imagine that your thought about touch, which we’ve just discussed, influences your pottery practice. Can you explain why you chose to devote yourself to this medium in particular, and how this practice helps to shape your overall understanding of tactility?

Porcelain mug, 2022.

Photo: courtesy of the artist

NB : Working with clay — touching and shaping clay — simultaneously mobilizes art, intimacy, and politics. Pottery is a sensual practice that involves pinching, kneading, and running one’s fingers against or into chunks of clay that can be firm, soft, wet, slippery, smooth, rugged, or hard. Especially during the first year of the pandemic, the intimacy of touching clay in the pottery studio and touching the soil and roots and leaves of my plants at home felt like practices that became more meaningful and more intimate. The intimacy goes beyond the making process. It brought me some comfort to think about pieces I had made and offered to loved ones, knowing that they were regularly touched, held, and gazed upon. Pottery is a particularly social practice involving several kinds of intimacy that are banal yet life altering, especially when grounded in community, in collective liberation. Capitalism, colonialism, and the carceral state do not physically isolate subjects just from each other, but also from ancestral practices used to connect with each other and with ourselves. Access to pottery spaces tends to be limited and shaped by income, whiteness, and ableism.

ADB : On your curated Instagram page @black_ceramicists, you explain that you searched for inspiration for your pottery practice on social media, and you observed that production by Black ceramicists doesn’t appear on accounts managed by white people. Noting that this erasure is not accidental, you sought to bring visibility to Afro-descendant ceramicists and to celebrate their work on your page. How does this “sanctuary of love,” as you describe it, for brothers and sisters in clay work make it possible to confront the adversity of white supremacy?

NB : I created the page in 2019, while I was living in the United States, around the time I decided to take pottery lessons. I think the first thing the page accomplished was to challenge the perception created, reproduced, and actively sustained by gatekeeping institutions and individuals that there are very few Black ceramicists, professional or otherwise. Both the abundance of Black potters I encountered and the relative ease with which I came across their work confirmed the white supremacist logics of “crafts” spaces and “makers” communities online and offline, as well as those of museums, galleries, and magazines. But it also revealed the tenacity of people whose mere presence in a pottery studio, ceramics program, or pottery exhibition or conference can be an act of political defiance. More access still needs to be created for poor, incarcerated, disabled, and neurodivergent people, but things have shifted since 2019. The second thing the page accomplished was to make it easier for Black ceramicists to find and connect with each other. Since 2020, several initiatives have launched. Kaabo Clay Collective is a social and mutual-aid network run by Black ceramicists for Black ceramicists. This year, at the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts annual conference, Adero Willard curated an exhibition called Clay Holds Water, Water Holds Memory, with art by nineteen Black women and Black non-binary artists working in clay. The collective also raised funds to secure passes and lodging for Black ceramicists who wanted to attend the conference, which was held in Ohio. I would love to see mutual-aid networks to support Black and Indigenous ceramic artists in and around Montréal.

Stoneware cup, 2022.

Photo: courtesy of the artist

ADB : “What can ceramics contribute to an abolitionist vision that centres Black liberation?” You asked this question directly to Afro-descendant ceramicists on Instagram almost three years ago. What do you remember of the exchange that followed, and how do you see the role that ceramics can play today in the dismantlement of the lethal institutions of the prison, the justice system, and the police?

NB : After writing that post, I learned about The People’s Pottery Project, a non-profit based in Los Angeles that was founded by, is directed by, trains, and employs formerly incarcerated women and trans and non-binary individuals. Pottery is a practice that has always been well positioned to foster sociality and intimacy either within communities or across lines of difference, and to nudge us toward developing tools and abilities to just sit with each other. And negotiating the sitting and sharing and touching can create bonds that challenge logics of competition, exploitation, and extraction. For those practices to be transformative, however, they have to disrupt the flow of capital, power, and resources, and this disruption is an essential part of what makes The People’s Pottery Project transformative. What other kinds of alternative circuits can deepen — through ceramics, for example — the quality of touch outside of dominant circuits of capital, power, and resources? Disruptive circuits and channels are the primary concern, but the collective practice can be ceramics, it can be dance, it can be acupuncture, it can be making out, it can be taking naps. In Montréal, many alternative circuits and channels already exist. DESTA, for example, is an organization based in Little Burgundy that provides re-entry and advocacy services to currently and formerly incarcerated individuals and to other criminalized community members. The love is there, in other words, and the love is what matters most.

Questions translated from the French by Käthe Roth

An author and researcher in the art field and a curator, Ariane De Blois holds a PhD in art history. She has been artistic director of Plein sud, centre d’exposition en art actuel à Longueuil, for three years.