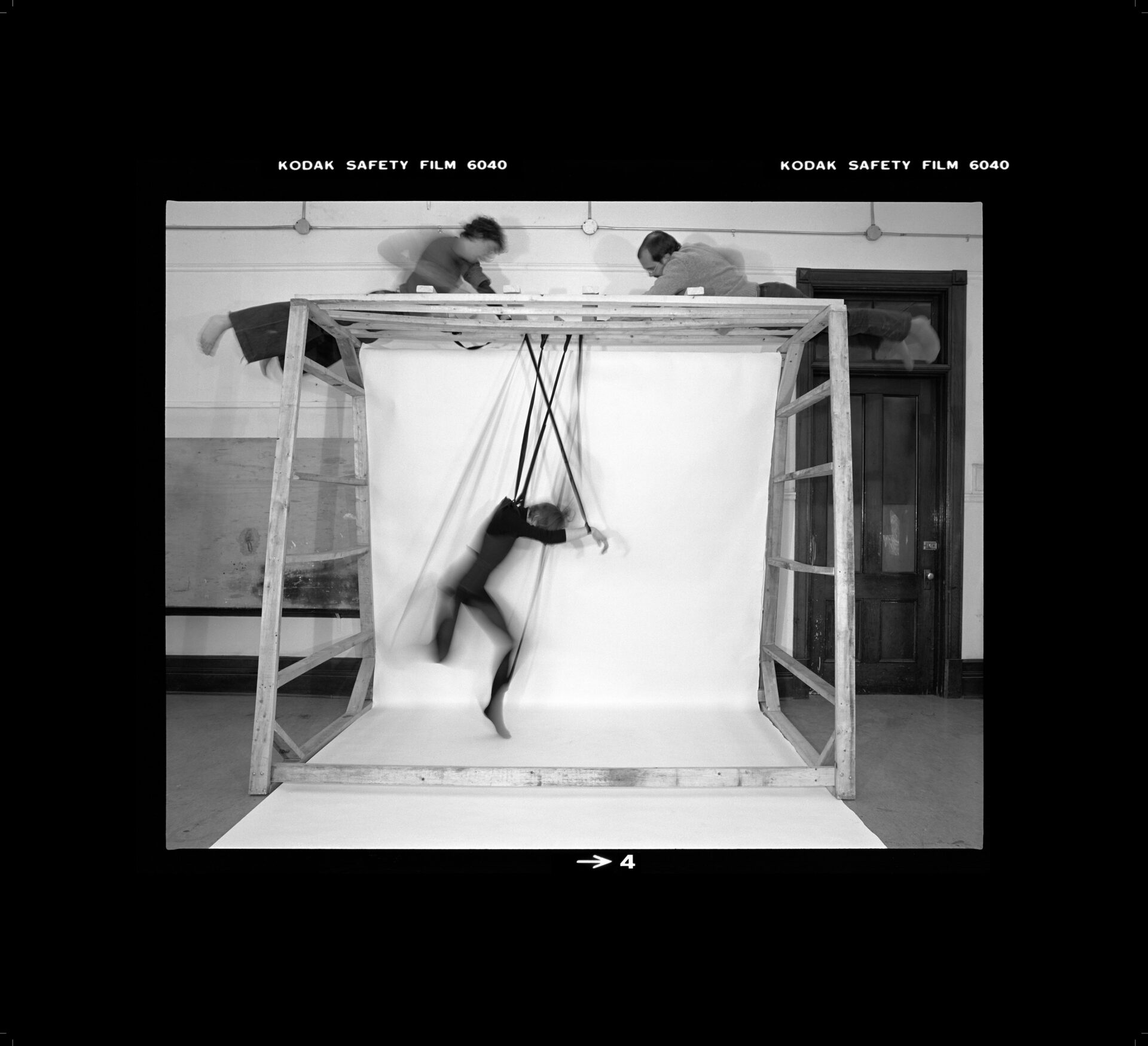

Jean-Jacques Ringuette, Figures de la masca- rade ou La vie passionnante de Félicien

January 29 – March 12, 2011

photo : courtesy of the artist

[En anglais] The last decade of artistic practice in Canada has been marked by a grow-ing interest in Renaissance themes and subjects, including cabinets of curiosity, rogue taxidermy, vanitas still lifes, grotesque hybrids, and carni-valesque décor and attire.

Recently on display at Occurrence, Jean-Jacques Ringuette’s photographs are a noteworthy example of this trend. An unset-tling exhibition, Figures de la mascarade ou La vie passionnante de Félicien combines contemporary aesthetic strategies with historical references to Medieval and Renaissance fools and tragic clowns, as well as Tarot cards, commedia dell’arte, carnival, and even the passion of Christ. The result is a somewhat off-putting exhibition, especially for a viewer unfamiliar with the historical precedents for these images. Without this context, many of the photographs verge on offensive. Les joyeux atermoiements du fatum, for instance, depicts the artist’s clown alias—Félicien—diapered, palsied, and sitting in a wheelchair surrounded by party favours, while in Je ne connais pas cet homme he vulgarly masquerades as an obese, disabled woman.

Although some of Ringuette’s images lack finesse, taken as a whole the exhibition is quite interesting. Perhaps its most valuable quality is an overarching strangeness rooted in a tension between humour and pathos, subtlety and exaggeration. In the accompanying catalogue essay, Penny Cousineau-Levine writes convincingly about the work’s relationship to concepts of the grotesque, carnivalesque, and abject defined by theor-ists such as Mikhail Bakhtin and Julia Kristeva. She reminds us that the modus operandi of a grotesque universe such as Félicien’s is to overturn “entrenched norms of sobriety, propriety and gender-appropriate behav-iour.” In Ringuette’s work, this is achieved through a tension of opposites in which avatars of childhood and senility, innocence and corruption, comedy and suffering are intermingled and confused. For example, a series of photographs based on carnival cutouts (also sometimes called comic foregrounds) twists the whimsical practice of sticking one’s head through a hole in a painted wooden façade into a macabre meditation on the intimate connection between birth and death, decay and regeneration. In these photographs, Félicien’s clown face replaces the head of a teddy bear stuck to a piece of plywood. In each image, the bear’s body assumes a different foolish or abject pose: slipping on a banana peel, wetting itself with greenish urine, sitting atop a pile of refuse, or losing control of its bowels. As with the rest of the exhibition, these are not the kind of images one spontaneously “loves.” Instead, their bizarre and confusing perversity gives one pause. In the current climate of easily digested, corporate- sponsored “hipness,” creating this kind of uncertainty in the viewer is no small achievement.