photo : permission de l'artiste | courtesy of the artist

Alain Laframboise’s photos evoke a skilful combination of realms through their use of shadows and their delicate play of light. Sculpture, painting, the discourses of art and photography are intertwined in visual compositions that are — at the same time — microspheres of art history. Using miniature objects as a basic element of his artistic practice, the artist sets the stage with figurines and small-scale props that, while not parodying ordinary reality, often raise questions about art history as part of what might be called a visual reverie. The photographed objects resemble statuettes and create tiny still lives, genre scenes largely covered in shadow and invaded by blackness. In his early years Laframboise produced scenic tableaux in boxes of various sizes that questioned Western art by deconstructing the two-dimensional surface, or by rendering pictorial space theatrical. These three-dimensional collages gradually gave way to photographs. Since 1989, the latter practice has provided the artist with a chance to devise points of view and compositions only accessible to viewers via this medium. Laframboise conducts his artistic research using three-dimensional montages and photos exploring representational modalities, in which the miniature object itself is the spearhead. In his last exhibition at Graff Gallery1 1 - Parcours, presented at Graff Gallery from February 7 to March 8, 2008. he presented a series of landscapes barely free of a penumbra that seemed to mask and conceal the objects that only occasionally emerged from total darkness. His figurative stagings operated in dialogue with Renaissance art theory; more specifically, with the precepts of Leon Battista Alberti, put forward in his De pictura in 1435. This work advocated for a new pictorial order manifest in the narrative components of painting; through invention (inventio), the depicted scene becomes both the object of a narration or description, and of a composition made possible by the arrangement of forms and body parts — an istoria. Each of the photos reveals a “micro” art history by making the miniature objects simultaneously fragments and privileged motifs. The objects pose a renewed challenge to Alberti’s great paradigms: perspective, and the notion of painting as a window open onto the world. The scenography of the miniature object, therefore, cleaves to a photographic account of art history.

photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

The small objects in the photographs are positioned — for the most part — in a non-space, one free of historical and geographical reference points, or other forms of identification. There are few indications of scale and the apprehension of the subject is largely arrived at by contrast. In The flower grows, an old man dies, the different light intensities produce a range of silver grey tones, creating an emerald-toned light. The image achieves its pictoriality not only due to variations of light and darkness, but also through the circulation of volumes marked by a proffered hand, open in an ambiguous gesture: offering or asking something of us. These object portraits recall the pictorial techniques of Venetian portraits from the first half of the sixteenth century. One recognizes the deployment of formless, sombre backgrounds from works by Titian, Antonello da Messina and Giorgione. The practice foregrounds an aesthetic of purity and heightens formal ambiguities. One can speak therefore of a deliberate mystification of the image and of its power to choose the way it will be perceived as a function of its construction. Nonetheless, these object portraits also seem to favour the ideal of the Mannerist artists, with which Laframboise is well acquainted by virtue of his years teaching art history. Through a taste for metaphor, rhetorical trope and scholarly citation, the staging of art history in the photographic arrangement of miniature objects positions itself as part of a search for an istoria a minima, the supreme model of painting according to Alberti. The istoria, a composition of figures engaged in an activity, here finds itself diverted towards the vegetable and mineral kingdoms. The scene set is a story of stone figures whose miniaturization blurs the boundaries between materials: thus, the photographed body offers an ideal passage between living model and still life. In Sweet, sweet, sweet, sweet… love… a stone foetus plays with this sort of indetermination. In a similar way the viewer questions the material in My eyes adored you… — is it a wax effigy, a mineral face, a death mask? Or is it implicitly a story about petrifaction? What is the status of a being — not to say a dream — made of stone, the living transported to the mineral kingdom? The shift of kingdoms lies at the root of the art — and the eye — of both photographer and Medusa; they have the power to petrify. Here is one characteristic quality of the Mannerist artist: to work with textures and colours metaphorically, while suggesting connivance, as if it were, above all else, important to affirm an aptitude for ingenium, the art of ingenious thought expressed with grace and precision, allowing us, in this case, to liken the work of the photographer to Freud’s Witz, or word play.

A Strategy of Fascination

Wunderkammer is a term used to denote a cabinet of curiosities — collections assembled by European princes from about 1560. They brought together works of art and natural curiosities, jewels and stones, exotica, mechanical toys, bizarre items, and miniatures.2 2 - For more on the subject one may consult a work by Patricia Falguières, Le maniérisme. Une avant-garde au XVIe siècle (Paris: Gallimard, 2004), or Kris Ernst, Le Style rustique (Paris: Macula, 1922). Such marvels also evoke what lies beyond the norm: the strange, the extravagant, the monstrous. A passionate antique-hunter, Alain Laframboise gathers up objects encountered during his wanderings through flea markets and constructs photographic histories for them. An articulated doll that’s a touch battered, a one-eyed teddy bear, a torn mask, leaden toy soldiers, Manga-inspired figurines with monstrous bodies, these fragments of childhood are diverted from their normal purpose and become art-historical characters. By meticulous work with photographic technology the artist adds meaning to them through a kind of figurative metaphor. A tiny wooden sculpture — with just a twist — becomes the Trojan Horse abandoned after the battle and presented to us in its condition as an object, with all sense of time abolished. The photographic image, sepa-rated from the human figure, plays with light and darkness — the whole thing becomes theatrical, almost disturbing. The staged object loses its scale and can therefore become a “supermotif” in the service of an istoria of a microhistory of art. The fragmentary hand in The flower grows, an old man die… recalls the interest given to this pictorial motif by the painters of the Cinquecento; the figure that points towards what should be seen in the image, the gesture of admonition, and the practice of self-portraiture are the hallmarks of this interest. The hand is the process that begins artistic research; it traces the multiple networks of lines. The hand also represents the formless beginning, the componimento inculto of Leonardo da Vinci. Seen in this way, the fragment has the freedom to decline itself into different states. Before being a part of the world to which it refers, it becomes a fragment of memory. The darkroom — once so familiar to photographers — is layered with a chamber of wonders, that of the figures and motifs of Renaissance art history.

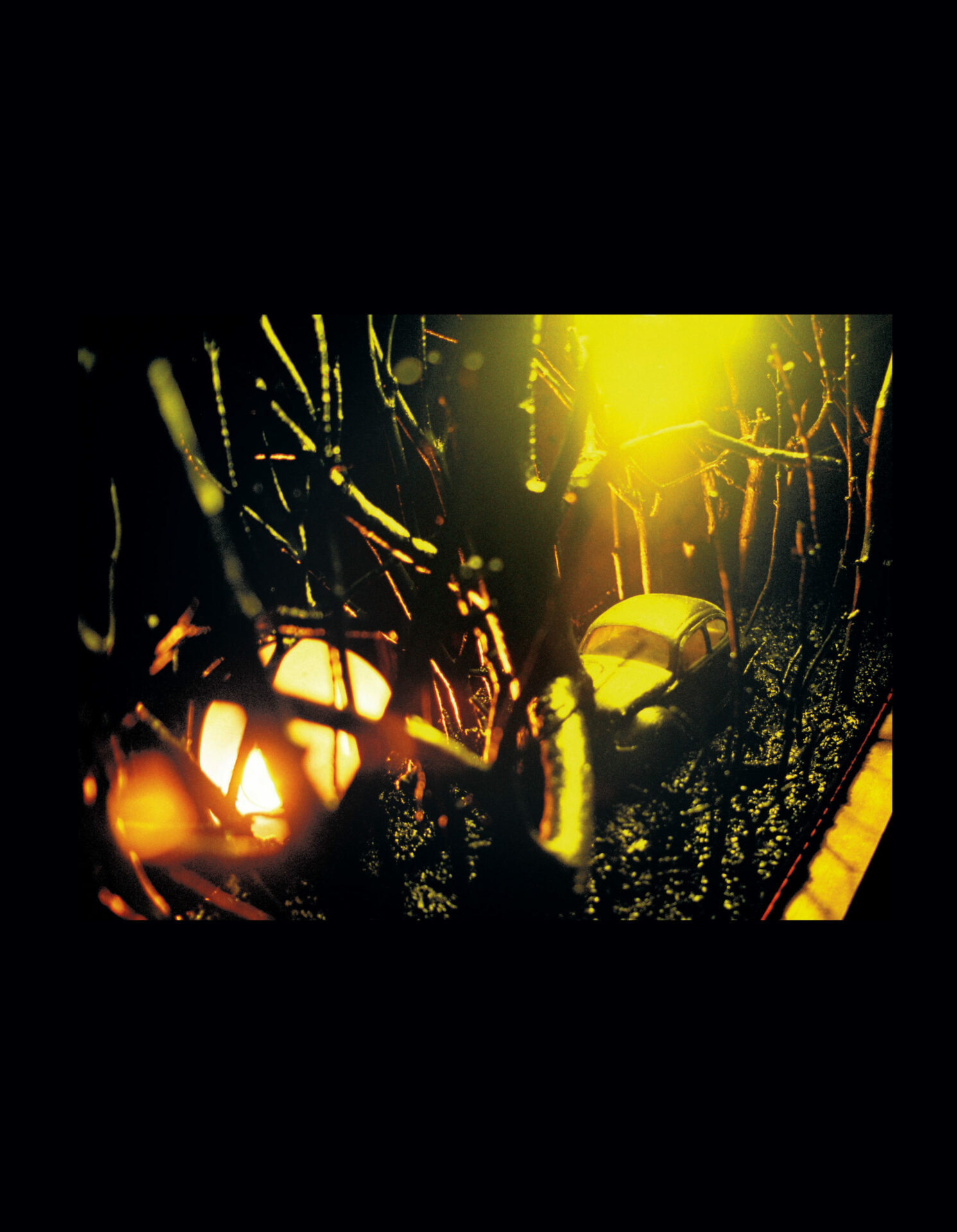

In 2008 Laframboise took up landscape photography, and this too through the use of miniature objects. The images’ scenography created visual traps that contained characters set in disturbing situations. Like the atmosphere of a detective novel, the enigma here is constructed of seemingly incomprehensible events, evoking unnerving landscapes, woven with a visual machinery of atmospheric effects. The relationship to space is made more accessible thanks to the miniature. From a theatrical composition to a perspectival space and passing through an affective landscape, these staged scenes distance themselves from reality and inevitably summon up a narration.3 3 - Nor are the titles insignificant; they make reference to old American songs (“The Four Seasons”, Diana Ross), relics of childhood that were played at Graff Gallery on the night of the opening.

photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

A Story of Scale

Alain Laframboise makes use of small objects in order to play with the hierarchy of dimensions and investigate the relationship between plane and volume. Photographic technology blurs the spatial reference points; stripped of perspective, depth seems to be missing, and in such a way that the viewer no longer knows the scale of the subject. But isn’t any question of scale in a photo a matter of pure interpretation? Scale establishes a relationship of proportion rooted in perception and in comparison to itself. Laframboise introduces a perceptual dynamic into his photos by creating an affinity between three kinds of scale: that of the final image, that of the size of the miniature, and that of the human — the real photographed object. He works with dimensional scales rather than anthropomorphic ones. The human body is not a constant in the scale, and to such an extent that the viewer no longer knows what is smaller, or larger, than he. While it might seem a truism, one notes that things perceived as smaller than one’s self are seen differently from things larger. Unobserved details appear, the variations of scale modify our view of the world. The intimacy established between viewer and object is inversely proportional to its size in relation to the viewer. Naturally, photography is tied to relationships of scale, but here we are dealing with a particularly strong case. It not only ensures the viewer’s gaze is anchored, it parodies or imitates certain visual atmospheres (as in the case of Découverte4 4 - Découverte was one of the photos exhibited at Graff Gallery in 2008. The series addressed the landscape in a detective novel ambiance. ), while modifying the point of view, detailing or providing a wider view, circumscribing the scene, interrogating the plasticity of the objects, etc. Due to the apparatus of miniature objects, the photographic frame — and what is outside of it — has a determining impact on the scenes staged; they dictate the level of fiction in the image and its legibility. Lording it, like a sovereign over a universe that belongs to him alone, the artist is free to choose what avenues of approach to the staged scenes remain open by revealing, or not, his creative process.

The photocompositions of miniature objects thus allow Laframboise to articulate an istoria of art history through his taste for Renaissance art. The micrological gaze of the photographer, in its singular care for detail, flirts with the idea that “the smallest cell of observed reality offsets the rest of the world.”5 5 - Theodor Adorno, Prisms (London: Spearman, 1967), 236. For Theodor Adorno, this arises from a philosophical posture shaped by a rejection of the primacy of the universal. The micrological gaze supposes that the particular is, every time, read in light of the painful contradictions between it and the universal, between the system and the fragment. This modality of the gaze allows the artist to restore what one might call effects of depth in which viewers are led to yield to the visual order so they can shake off surface effects and apprehend visual mediation.

[Translated from the French by Peter Dubé]