Photo: Kathryn Carr, © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New york

Signalled by the rise of theories and practices of performance specifically addressing temporality and repetition, the notion of re-enactment is in the air. Scholars have developed a critical discourse pointing to the impossibility of a single act existing in plenitude (the act is always already contingent on our experience of it, and on the various modes through which we remember and historicize it), but some artists, curators, and increasingly popular culture re-enactment societies in Europe and North America promote the idea of re-enactment as a means of retrieving the truth of the past.1 1 - See Rebecca Schneider, Performing Remains in Visual Culture: Essays on Re-enactment (New York & London: Routledge, 2011).

While the term re-enactment has gained new purchase since the turn of the millennium, with new concerns about our relationship to history, it has been argued that history itself, all culture, even human experience in general, are necessarily based on a logic of re-enactment or redoing. As Adam Mendelsohn argues, “[u]nderpinning re-enactment art is the implication that the activity of making art itself, participating in cultural production, is itself a kind of historical re-enactment — an activity that preserves heritage through ritualized behavior.” Or, as Robert Blackson puts it, reflecting on the phenomenon of false memory in relation to artistic re-enactments, “memory, like history, is a creative act.”2 2 - Adam Mendelsohn, “Be Here Now,” in Art Monthly 300 (October 2006), 13 — 16; Robert Blackson, “Once More… With Feeling: Re-enactment in Contemporary Culture,” Art Journal, Vol. 66, no. 1 (Spring 2007), 31. Notably, in the 1950s, British historian R.G. Collingwood argued that history can only be retrieved by “re-enacting” it through identification; see Collingwood, The Idea of History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1956), 215.

If history and memory themselves involve a process of performative re-enactment, what about histories of art and of performance and live art themselves? Drawing on theories of performativity by twentieth-century linguists and philosophers from J.L. Austin to Jacques Derrida to Judith Butler, one could argue that the arts are all redoings of one kind or another: either repetitious restagings based on a script (as in a classical music concert, a dance event, a conventional theatre production, or even performative Fluxus artworks from the 1960s), or a process of reworking past styles and themes to move art forward in a fantasy of increasing sophistication and/or aesthetic improvement (as in modernist Euro-American models of art history). But, with its roots in theatre and visual arts production, and with its recent popularity as much in the art world as in activist and participatory contexts (a popularity that renews and reworks strategies common to radical art practices in the 1960s and 1970s), performance art has a particularly strong, if also contradictory, relationship to the idea of enunciation as “repetition” or “reiteration.”3 3 - The notion of iteration, taken from linguistic theory, is central to the theorization of the performative on the part of Jacques Derrida and later, Judith Butler. See the latter’s “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal 40, no. 4 (December 1988), reprinted in Feminism and Visual Culture Reader, ed. Amelia Jones (London: Routledge, 2003), 392 – 401. The live or performance art event, one could argue, exemplifies the iterative nature of all bodily enactment (or even of all human experience tout court) as well as evoking the yearning for authenticity and presence that continues to encourage us to privilege the “live” over the “representational.” Yet the live event, precisely because it can never be fully remembered or recorded, also makes clear the failure of the re-enactment to secure authenticity.4 4 - On this point, see my essay “‘Presence’ in absentia: Experiencing Performance as Documentation,” Art Journal (Winter 1997 – 8), 11 – 18; reprinted with a new introduction as “Temporal Anxiety/‘Presence’ in Absentia: Experiencing Performance as Documentation,” in Archaeologies of Presence: Acting, Performing, Being, ed. Nick Kaye, Gabriella Giannachi, and Michael Shanks (New York and London: Routledge, 2012), 197 – 221; and Philip Auslander, Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture, second edition (New York: Routledge, 2008).

Pil and Galia Kolletiv have noted that there is a way for this failure of authenticity to function critically: “a historical moment is never new, which means that there is no original to repeat.” They continue, drawing on Michel Foucault’s notion of history without “landmark,” to argue that a “successful re-enactment would [produce a disloyalty to the point of origin which]. . . does not amount to historical relativism, but rather activates history from within the present, allowing us to move away from the sterile attempt to cut through the infinite mediations of the spectacle.”5 5 - Pil and Galia Kollectiv, “RETRO/NECRO: From Beyond the Grave of the Politics of Re-enactment,” in ART PAPERS, [accessed April 15, 2013,] www.kollectiv.co.uk/Art%20Papers%20feature/reenactment/retro-necro.htm. I would add to this that re-enactments that do not acknowledge these paradoxes get caught up in the discourse of authenticity and genius, ultimately resting on an impossible (yet still intransigently common) notion of retrievable original meaning and artistic intentionality.

Histories of performance art proper (that is, the genre defined by authors such as Roselee Goldberg) have tended to devolve around a handful of iconic photographs and textual descriptions, or in some cases film or video footage — reverting to an art historical, and art-market-driven model of history that privileges individual genius over the vicissitudes of community, social history, or ontological questions about what performance can do to audiences, institutions, and marketplace structures. Until recently, this reliance on these documents and descriptions was rarely put under scrutiny — or exposed for the way in which it paradoxically reduces the celebrated “live” act to singular (and commodifiable) objects of display and exchange. One point of tension in this model is raised by the fact that works are re-enacted in order to be “known” historically: the massive resurgence of interest in legacies of performance or live art since the early 2000s has increasingly been worked through in relation to some variation on a newly developed re-enactment format — whether this means literal performance works redone by the same or a different author (such as Marina Abramović’s well-known Seven Easy Pieces project, performed at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 2005),6 6 - For an extended analysis of Abramović’s Seven Easy Pieces and her other recent works, see my “‘The Artist is Present’: Artistic Re-enactments and the Impossibility of Presence,” TDR: The Drama Review 55:1 (Spring 2011), 16 – 45. or restagings of political protests or events (the work of Jeremy Deller, or of Sharon Hayes, whose projects have involved having herself photographed with signs from historic protests at the sites of the original events).

One could argue that the mere fact of performing a historical or artistic event again encourages a critical relationship to liveness — at the very least, a questioning of the status of the event itself both within performance history and as a potentially reified object or document in museum exhibitions and art histories.7 7 - On the status of the event in visual arts discourse, see Charles Merewether and Johns Potts, eds., After the Event: New Perspectives on Art History (Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 2011). The key point made by re-enactments, whether this is the intention of the re-enactor or not, is that the past is impossible to retrieve as it existed in the past (that in fact the event is always already “over”).

While Abramović’s restagings might seem at first glance to pivot around strategies of “appropriating” works by famous performance artists linked to the appropriation strategies common in 1980s visual art, particularly in the practices of successful New York City artists from Sherrie Levine to Barbara Kruger to Richard Prince, the Seven Easy Pieces project contrasts strongly with this avant-garde gesture of “critiquing” structures of authorship (certainly Abramović’s published comments suggest otherwise, privileging the greatness of the artists, such as Joseph Beuys, whose works she chose to redo). As it was presented and received, and is (now) being historically framed, Seven Easy Pieces itself becomes constructed and viewed as a set of “original” acts, revolving around the name Abramović.8 8 - This tendency has been exacerbated in Abramović’s efforts such as her solo re-enactment of her 1980s work, with Ulay, Nightsea Crossing, in the 2010 retrospective (titled, tellingly, The Artist is Present) at the Museum of Modern Art, New York; see my essay, “‘The Artist is Present’: Artistic Re-enactments and the Impossibility of Presence.” On Seven Easy Pieces, including Abramović’s comments about the work, see Abramović, Seven Easy Pieces (Milan: Edizioni Charta, 2007), and my interview with Abramović, “The Live Artist as Archaeologist,” in Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History (Bristol: Intellect Press, 2012), 543– 66. Such re-enactments as currently presented and institutionalized in exhibitions, books, and films are thus definitively not presented as critiques of modernist structures of authorship and value, but come to be about the very way in which live acts come to mean and have value through authorial structures of ratification and commodification.

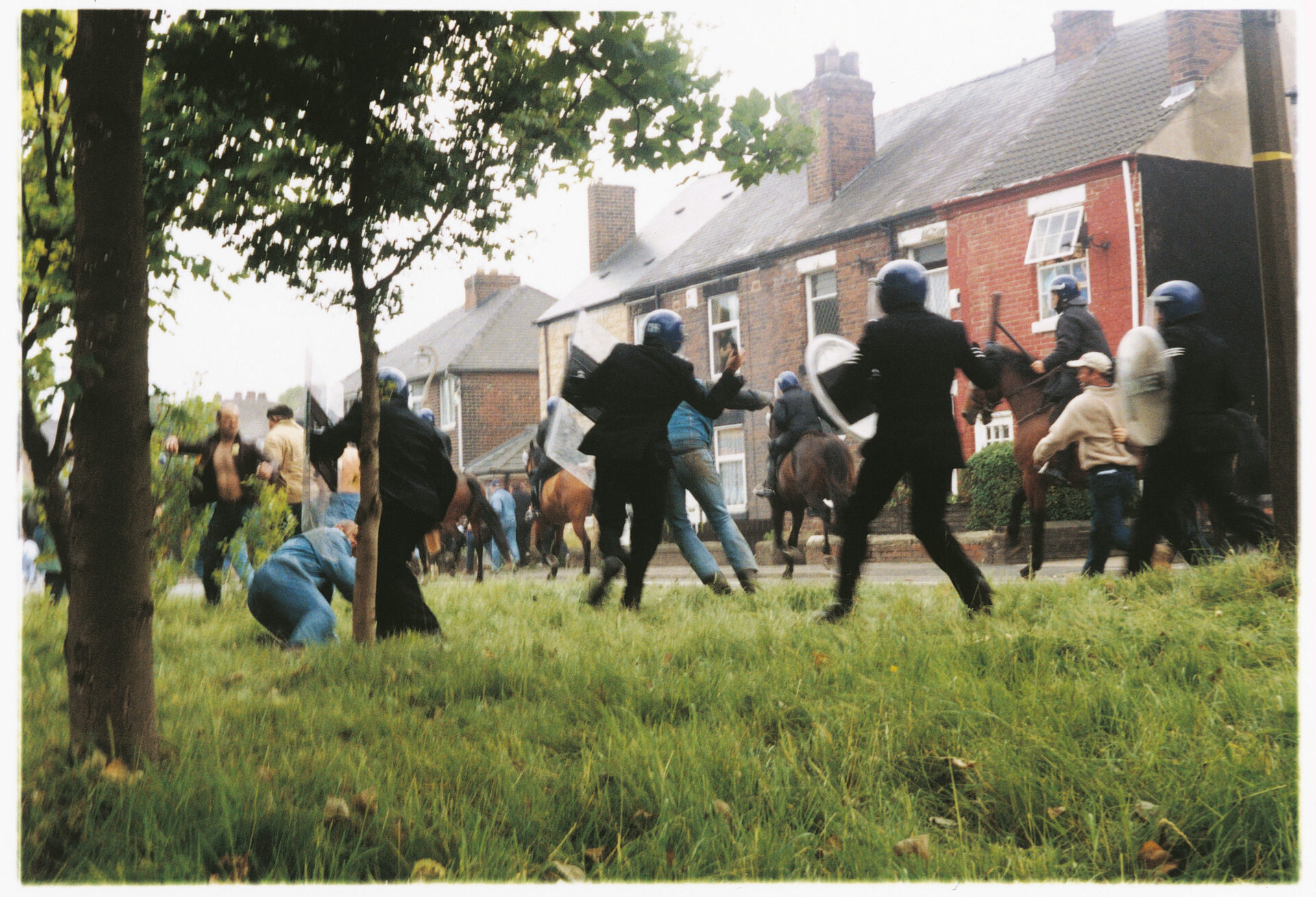

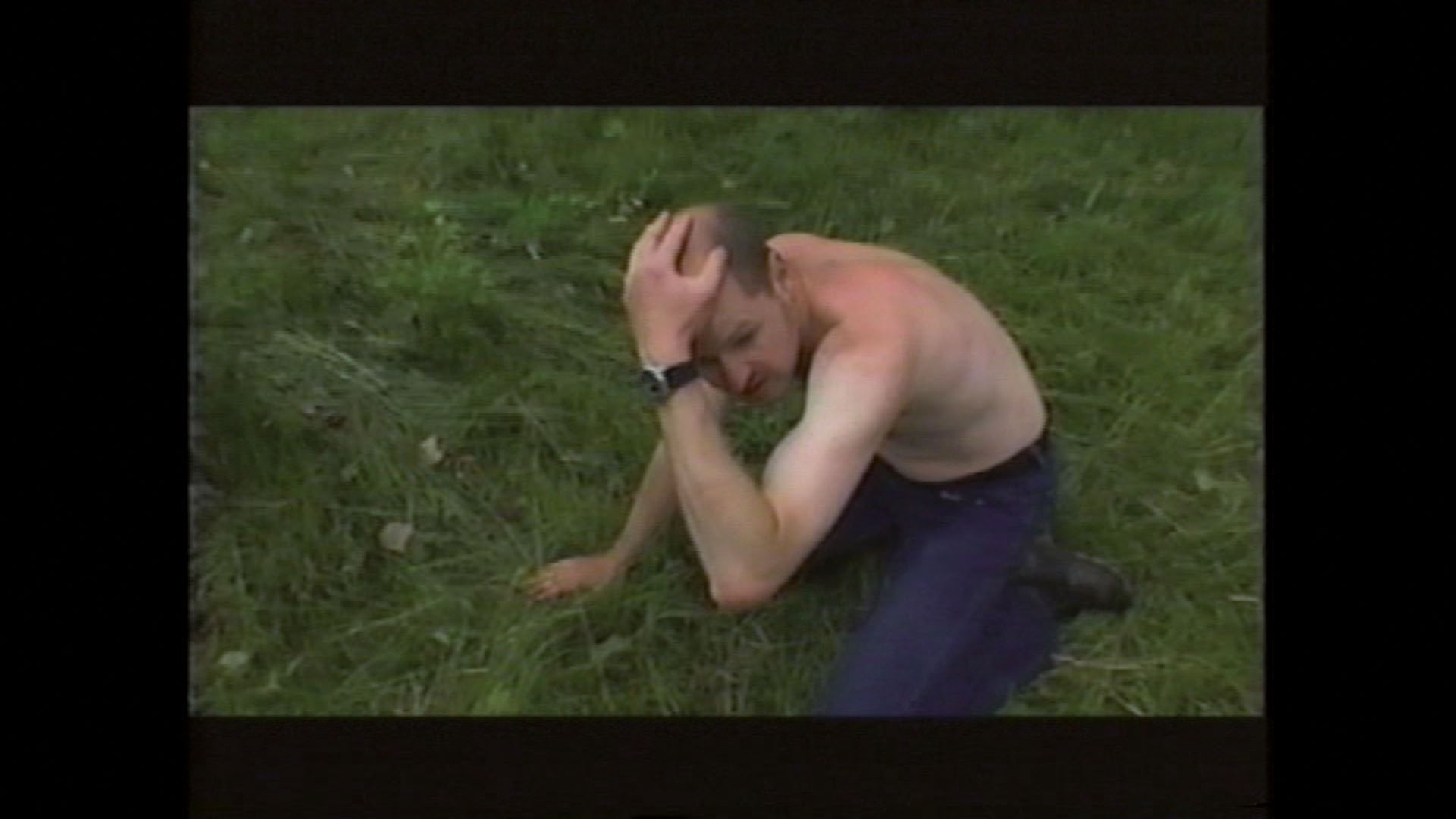

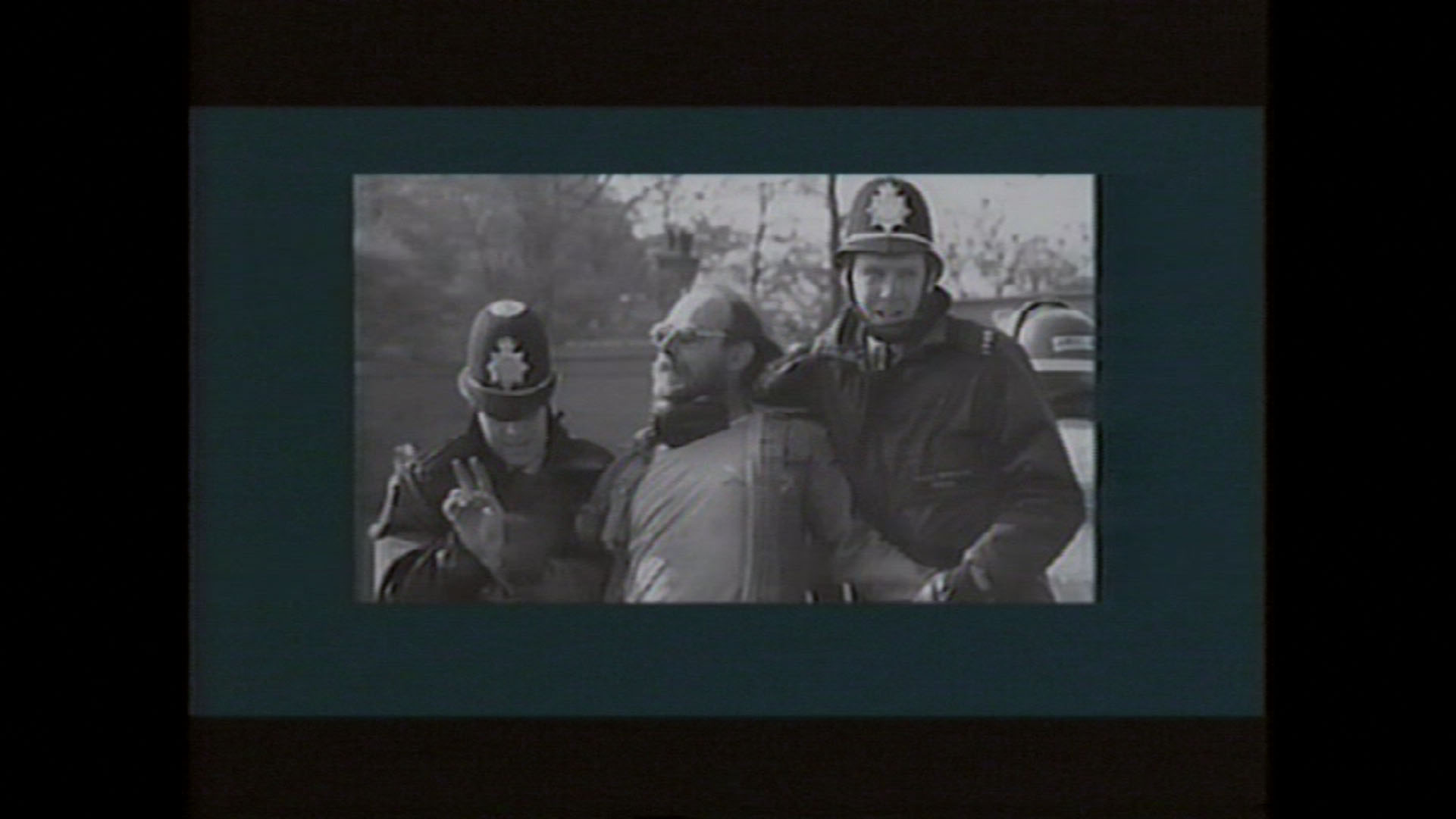

A different case again is Deller’s re-enactment of the 1984 British miners’ strike in Battle of Orgreave — a restaging of a political event that, as noted, Deller is careful to keep in process as a work, thus continually “activating history from within the present,” which, as Pil and Galia Kolletiv noted, was a key strategy in stressing a “disloyal” relationship to an impossible-to-know past. Battle of Orgreave has taken the varying form of a film of the re-enactment by Mike Figgis, screened originally on Channel 4 in the UK in 2002, and subsequent presentations of the film along with artefacts from the original strike and the redo in art galleries. Deller’s complex project stems from apparently different motivations from either the 1980s appropriationists or Abramović and reaches completely different audiences with different effects. Deller, who is a full generation younger than Levine and Abramović, does not “redo” previous works of visual or performance art. He restages a political event, conveying this process through popular cultural (TV) as well as art contexts, interrogating not just art value systems but the very structures of the art market, political power, and the modes of collective memory through which events take place and then take on meaning after the events themselves are over. Deller’s work, like that of Sharon Hayes and many other artists of his generation (born after 1960), points to the contingency of meaning and value in relation to the complexities of memory and the way in which histories are written.

The Battle of Orgreave, June 17, 2001.

Photos: courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s enterprise

Re-enactments, like the live in general, might seem to promise an escape from commodification in their ephemerality — certainly Abramović does not explicitly attempt to promote the historical performance first and foremost as a commodity. But of course, that is what her re-enactments become, particularly as they circulate out from such a major art institution as the Guggenheim, and via the carefully choreographed professional photographs, film, and books that have been produced in relation to Seven Easy Pieces. Far from romantically ensuring that the act never becomes commodified through an attenuation of its temporality by redoing it at a later time, the re-enactment often (if not always) ends up congealing in relation to structures of capital — often via its own documentary traces. As Sven Lütticken asks, “[l]ike other performances, re-enactments generate representations in the form of photos and videos. Is it the fate of the re-enactment to become an image? And are such representations just part of a spectacle that breeds passivity, or can they in some sense be performative, active?”9 9 - Sven Lütticken, “Introduction,” Life, Once More: Forms of Re-enactment in Contemporary Art, ed. Lütticken (Rotterdam: Witte de With, 2007), 5. And, in relation to the practice of Francis Alÿs, art historian Grant Kester adds to this a critical observation on the way in which such commodifications function to reinforce the authority of the artist by noting, “it is precisely in the circulation of the event-as-image before a ‘global audience,’ as Alÿs writes, that he is able to accrue the symbolic capital necessary to enhance his career as an artist. . . .”10 10 - Grant Kester, The One and the Many: Agency and Identity in Contemporary Collaborative Art (Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2011).

The re-enactment almost always circulates as images or objects to be bought and sold, whether literally (as artworks) or figuratively (as cultural capital to bolster careers); by redoing earlier works, the artist draws on the previous artist’s name to further her own career: just after Abramović’s redo of Joseph Beuys’ How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965), in her 2005 Seven Easy Pieces, if one searched “Beuys hare” in Google Images, most of the first page of images that came up were of Abramović rather than of Beuys himself performing the piece. Re-enactments can and do participate in what business theorist Jonathan Schroeder has called developing the role of artists “as brand managers, actively engaged in developing, nurturing, and promoting themselves as recognizable ‘products’ in the competitive cultural sphere.”11 11 - Schroeder, “The Artist and the Brand,” European Journal of Marketing 39, no. 11/12 (2005), 1292.

Never inherently eschewing the market (far from it), nonetheless the performative re-enactment reminds us of how such value systems function in historical terms, of how curators and historians write certain things into the present, exclude others, and continually fix and re-fix the meaning of objects as well as events in order to bring them into a continually refreshed “present” (with that “present” inevitably including the circuits of the marketplace, which itself makes and informs “histories” as we know them). Crucially, however, in the end re-enactments remind us that all present experience is only ever available through subjective perception, itself based on memory; all “events” — those we participated in as well as those that occurred before we were born — can only ever be subjectively enacted (in the first place) and subjectively retrieved later. There is no singular, authentic “original” event we can refer to in order to confirm the true meaning of an event, an act, a performance, or a body, presented in the art realm or otherwise.

Any claims of establishing authenticity through re-enactment put the lie to their own claims: the status of the live artwork or event is never “authentic,” never retrievable in singular form as truth. The event is only ever known through the continual unspooling of memory as itself a kind of creative (and never fully reliable) re-enactment of the past. As such, the mode of re-enactment points to the event as always already experiential and interpretive (as well as interpreted).