Photo: Bettina Hoffmann, courtesy the artist & Centre Clark, Montréal

The image of the contemporary art collector is often associated with appearances and with luxury, so it’s no coincidence, then, that this cliché drives the parodic work of Marc-Antoine K. Phaneuf (MAKP). On the other hand, the interest in pulling closer the existential malaise revealed by our relationship to objects — that of always aspiring to be more — and the argument about the collector put forward by Jean Baudrillard in The System of Objects doesn’t lie in those qualities. For Baudrillard, the act of collecting and the activities inherent in it — arranging, classifying, manipulating — consist of a primary reflex developed by a child in order to master the world around it.1 1 - Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects (London: Verso, 1996), 87. From the start, collected objects play a role in managing anxiety; they give the subject who accumulates them a feeling of mastery over his or her immediate environment while reassuring them of their identity. In fact, Benjamin sees the discourse of subjectivity exemplified in such objects, since through them the subject not only projects a specific image of him or herself, with which s/he wishes to be associated (our objects act as a mirror for a desired image and not a real one),2 2 - Ibid., 89. but these objects also allow the subject to place him or herself beyond time by conjuring the fear of death. One could go so far as to suppose that it is a feeling of lack, a feeling of not being enough that drives one to collect. The activity thus produces a compensatory effect as it aims to make an individual’s desire for accomplishment — the supreme contemporary value if there ever was one — tangible by piling up the material goods associated with the idea of social success. This is the reason Baudrillard identifies the passion for private property as the engine that drives the collector’s act.

“Every object thus has two functions — to be put to use and to be possessed,”3 3 - Ibid., 86. explains Baudrillard. He adds, “the pure object, devoid of any function or completely abstracted from its use, takes on a strictly subjective status: it becomes part of a collection.”4 4 - Ibid. It is through subjective investment, then, that the object supports the individual, taking part in what he or she is. And Baudrillard stresses the fact that the object’s degree of abstraction grows through its multiplication: in a collection the abstract value of a material possession can overtake its use value, thanks to the organized way in which the objects refer to one another. This is why one imagines a collection represents, in its quintessence, the logic lending an individual’s objects and goods a role in the development of his or her personality.

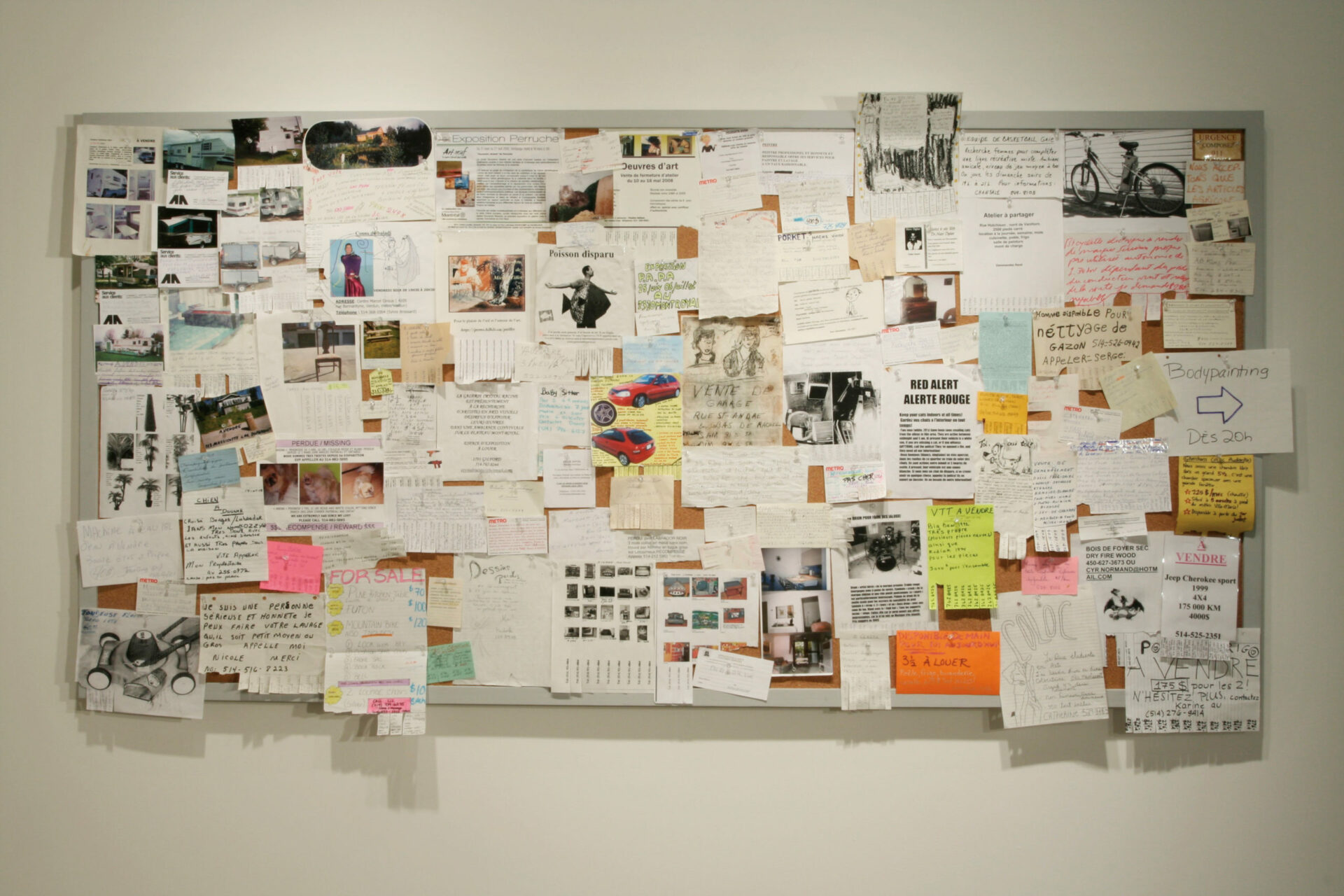

MAKP’s process also seems to rest on such stakes. His Collection de trophées (2009) exhibited last autumn at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery of Concordia University as part of the Off-Biennale de Montreal, doubly evokes the symbolic role Baudrillard has the object play: first by the very nature of the displayed products — trophies — and then by their accumulation; these trophies form a collection.

Collection de trophées, Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen, Montréal, 2009.

Photo: Guy L’Heureux

Positioning itself in the genealogy of the ready-made, the work recalls the displays of major shops and department stores — a universe familiar to the artist who, as a poet, amused himself with this image in his collection Téléthons de la grande surface (inventaire catégorique) (2008). For the exhibition, a full wall of the gallery was painted a bright cotton candy pink and covered with shelves on which sat nearly 160 trophies of every size that had been bought in lots, or found in flea markets. Only one of the trophies was actually won by the artist during a disputed hockey tournament in Saint-Hyacinthe in 1994, when he was just 13 years old. One might well imagine it is the founding element in a nonetheless heteroclite collection. Winking at contemporary art (René Payant, General Idea, Ève K. Tremblay) and at Quebec personalities, as much those we remember as those we might like to forget (Marie-Soleil Tougas, Valery Fabrikant, Vincent Lacroix, Dédé Fortin et Vincent Lecavalier), the trophies direct our attention to some banal accomplishments that are nonetheless consecrated by this object of distinction: “Donnaconna Optimist Club. Joseph Provencher,” “Strong Man Meet 2007. 19th Benjamin Ruel,” “Limoilou Nordiques. Consolation Prize,” “20 years of Service.” Of course, we surmise that some of the plaques have been modified to solicit a smile (“Child King”) or unease (“Rosemont White Sox. Best av. at bat: Marc Lépine”), but in other cases the alteration is more difficult to detect.

Like works of art, the trophy has no use value: it is defined by its symbolic value, which is concretized in its appearance — the richness of its materials, its shine. Its function is to manifest the success of its recipient. The artist Aleksandra Mir, whose works are also trophies, says this aesthetic arises from the tradition of silver chalices produced by the church in the Middle Ages.5 5 - Matthias Ulrich (interview with Aleksandra Mir), “Letting go!,” Aleksandra Mir. Triumph (Frankfurt: Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, 2009), 54. Objects connected to religion reflected the spiritual power of those wielding them. The Church is one of the institutions, along with, notably, royalty, to transform its objects into genuine incarnations of power; a power made visible by the great attention given to the ornamentation of those objects. Compared with them, the plastic trophies collected by Phaneuf with their gilding, columns of false marble and figurines posed as if shouting “Victory!” are more likely to make one laugh… a forced laugh. In fact, the artist’s substitutes — objects of pride (and power) for their previous owners — are clearly an indication of just such a quest for recognition, this desire for immediate gratification in the midst of which an existential malaise appears. Ironically, the previous holders flattered their egos with mass-produced objects. This standardization is made more than visible in the collection exhibited at Concordia; there the figurines and models are repeated. Faced with a bargain basement display, we can’t really know what to think; it throws us back, meanly, on our own desire for honour, our own need to arouse envy in others. An immense and embarrassing gap opens between the poor quality of these generic trophies and the sentiment of individual accomplishment they are supposed to represent. And what worse than that aggressive cotton candy pink to — rather than help one forget the awkwardness — make it more oppressive?

It is difficult to discern Phaneuf’s actual position in regard to his collection: to make us laugh, or to laugh at us? Since, if the trophy is clearly an object whose symbolic value comforts the one to have won it by reflecting a positive image of him, how can a collection of unmerited trophies provide the collector MAKP with a feeling of satisfaction? We can only suppose that in admiring these objects, brilliant with artificial lustre, the artist-dandy — a label that fits Phaneuf perfectly — tells himself that he is far beyond all that: that obsessive thirst for recognition that some quench in lusting after symbols of victory, and others by throwing themselves onto the dizzying ride of consumption and luxury. And still, the artist doesn’t hesitate to connect — like Baudrillard — the pleasure of collecting with the passion for private property, going as far as finding in the figure of the artist-collector that of the artist-consumer.6 6 - Interview with the artist, October 5, 2010.

The artist-collector, the artist-consumer, but also the artist-dandy having made of his daily life “a formal apparatus,” considers appearance rather than being as the one tangible reality.7 7 - Nicolas Bourriaud, Formes de vie. L’art moderne et l’invention de soi (Paris: Denoël, 2003), 37-44. Nicolas Bourriaud speaks of the dandy as one who evokes “affectation, contempt of class, the fashion plate, emptiness” and “an ascetic dimension” and “self-fashioning” equally.8 8 - Ibid., 45. These are the two levels on which MAKP seems to play. He doesn’t hesitate to construct himself, modifying even the name by which he is designated (by adding the initial “K” which is not filial), all the while scrupulously watching the effect he produces in public, wearing a suit, tie, brightly coloured shirt and mock croc shoes like a second skin. His image, the figure of “the artist” he has built, is the horizon against which his work (literary, artistic) takes on sense — a logic that inverts that of the collector, who tends to leave the function of constructing his sought-after image to his possessions. Meaning is always ambiguous with MAKP, it raises doubt in the viewer or reader. It is because the artist mixes the worlds of popular and elite culture in his work that its ideal receiver is difficult to determine. One doesn’t ever know whether or not he is making a judgment about the people and situations he references.

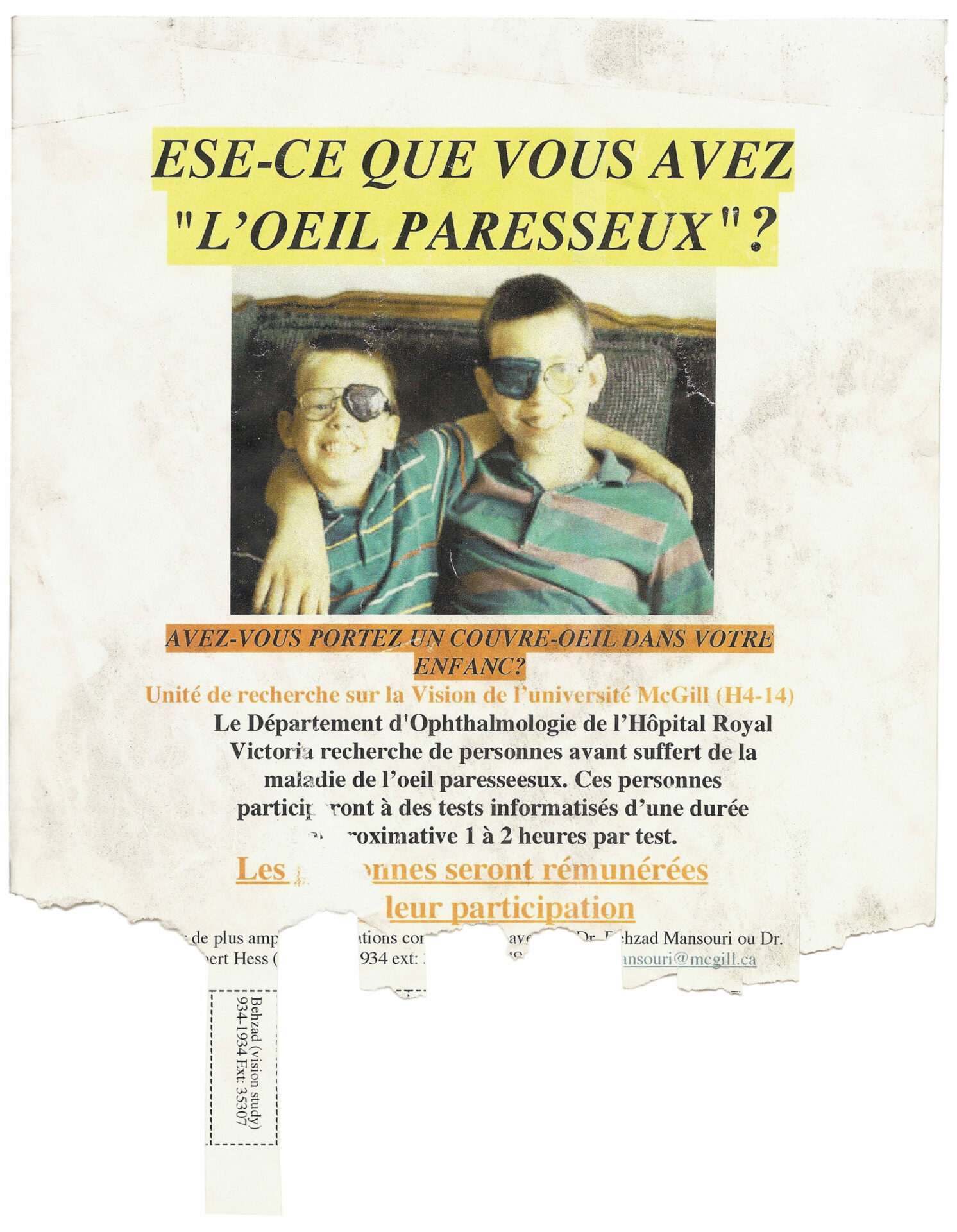

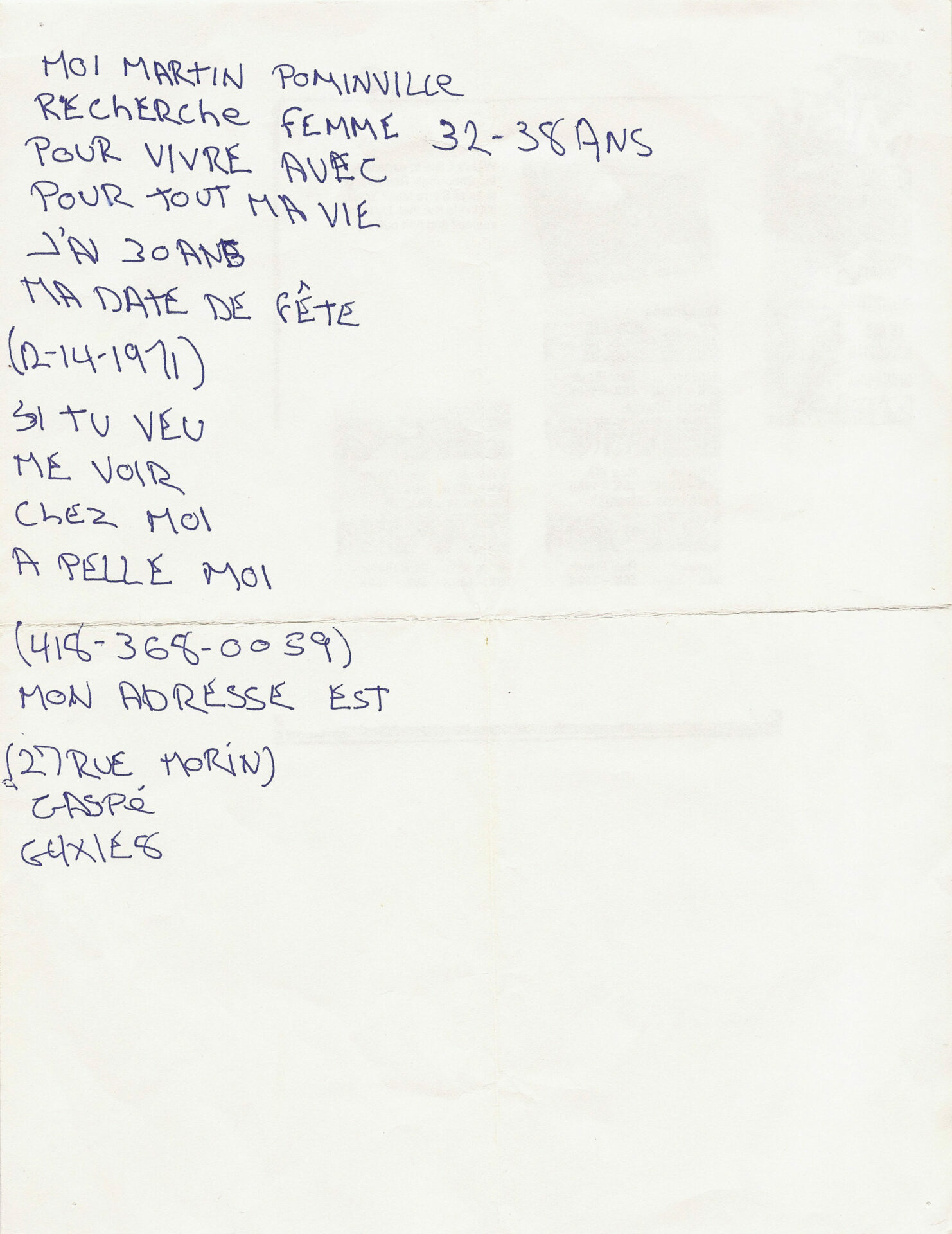

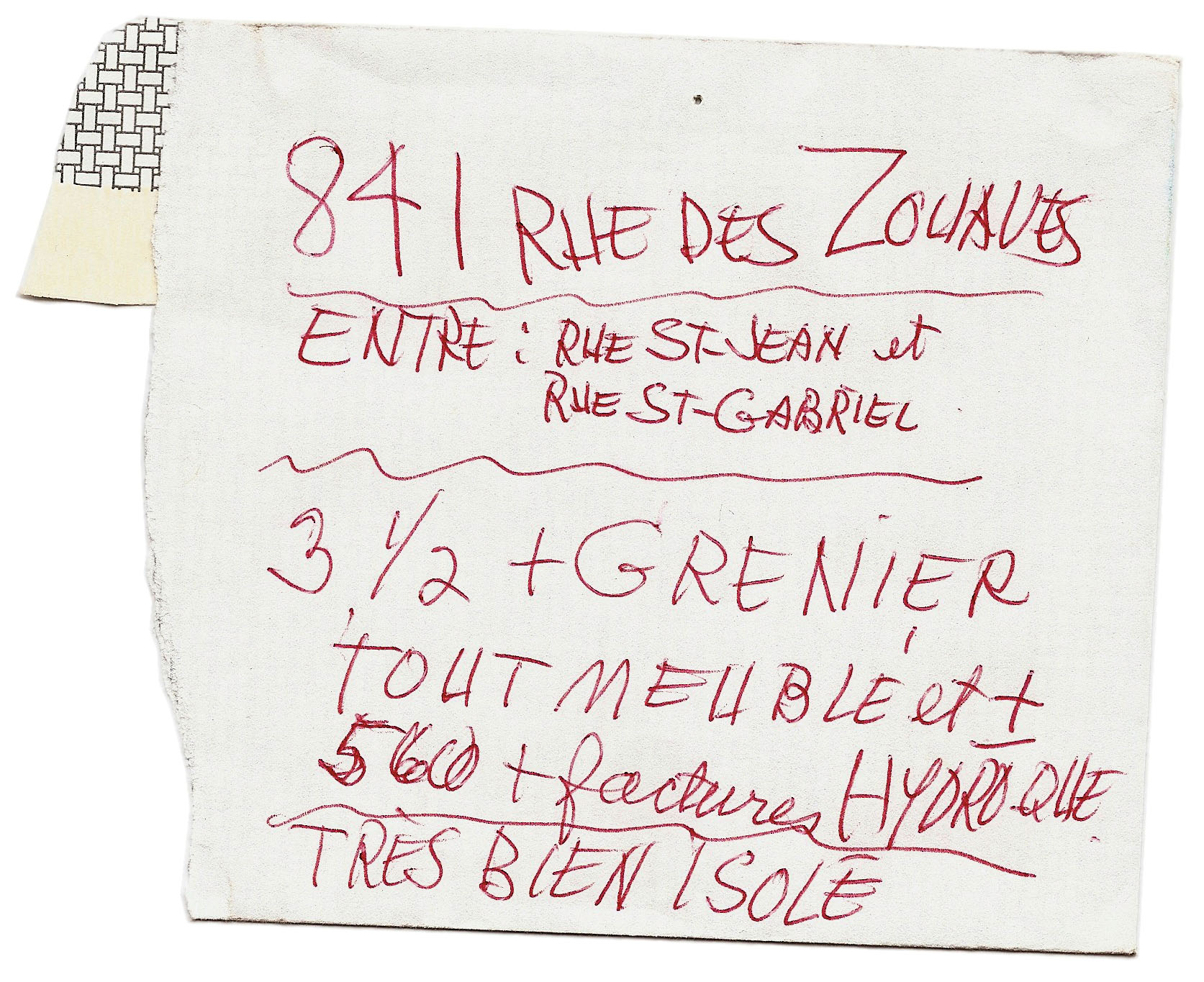

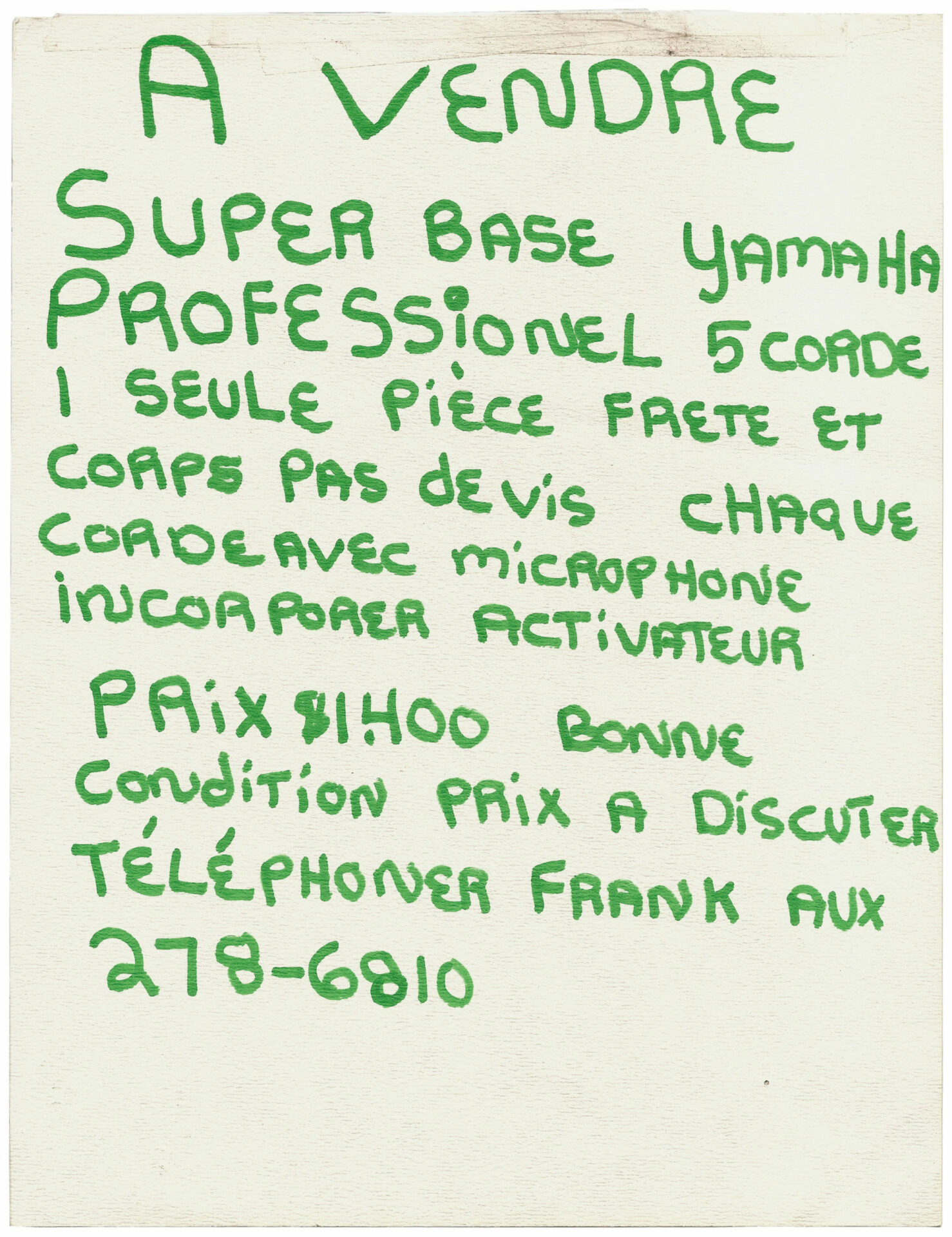

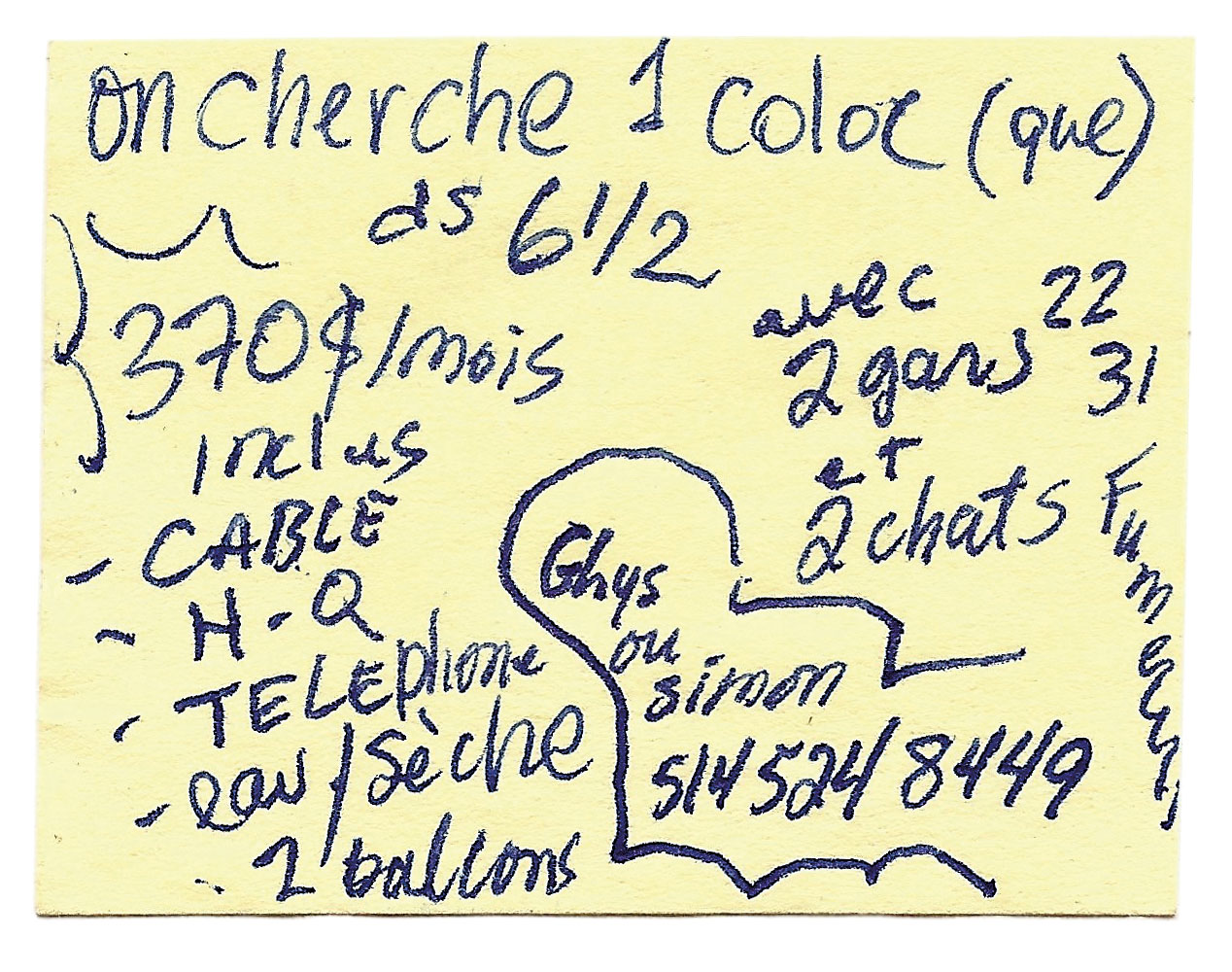

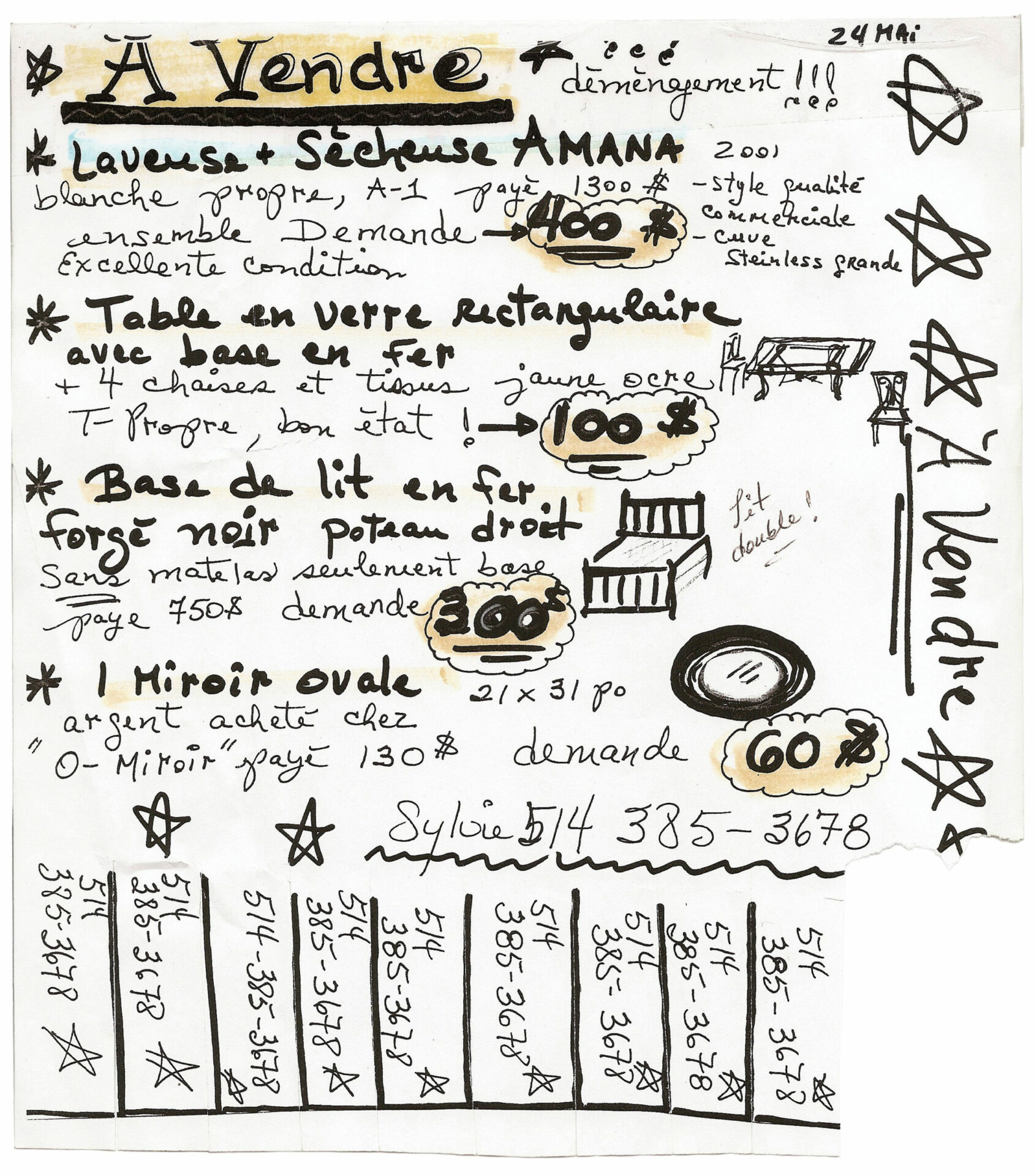

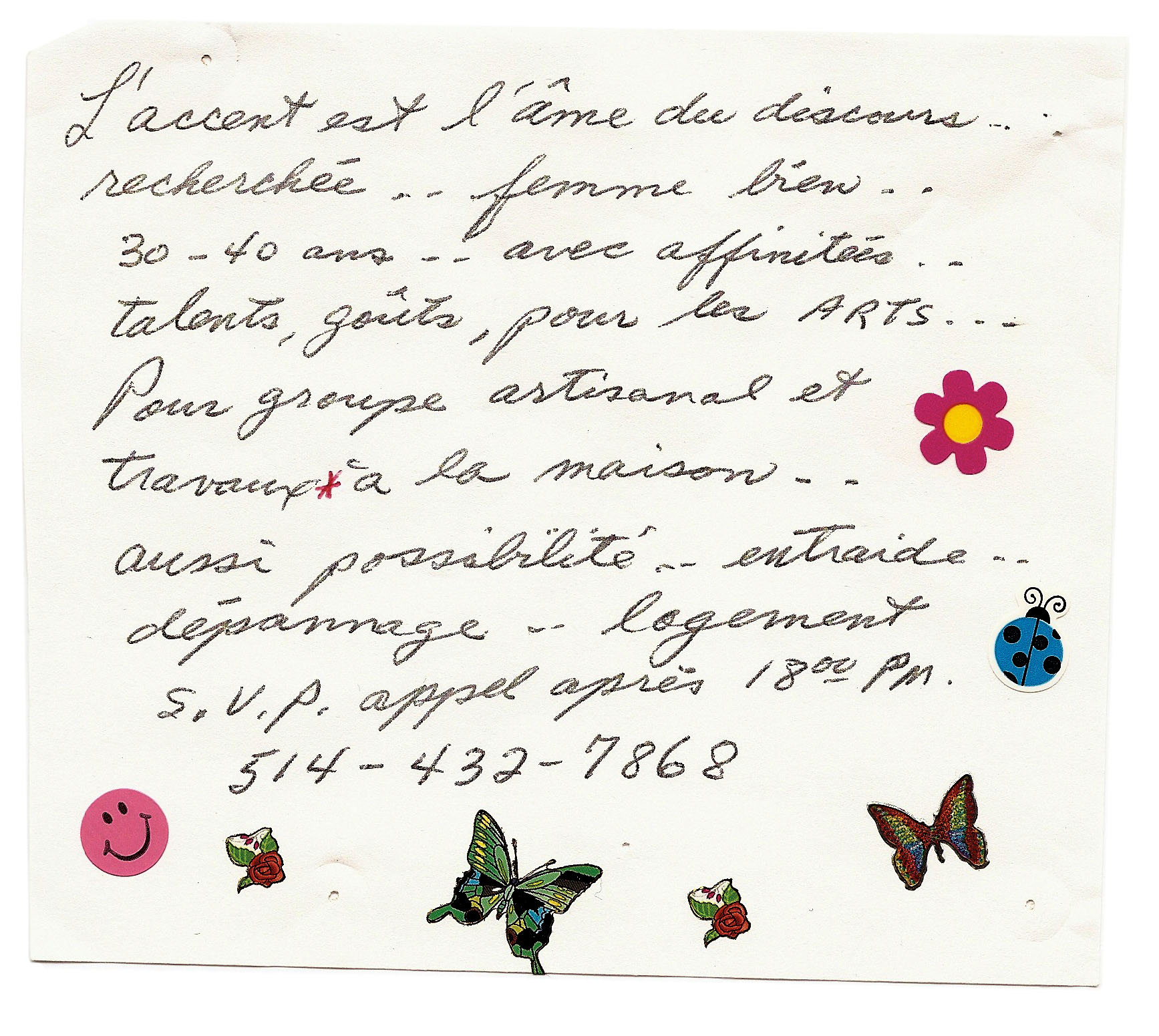

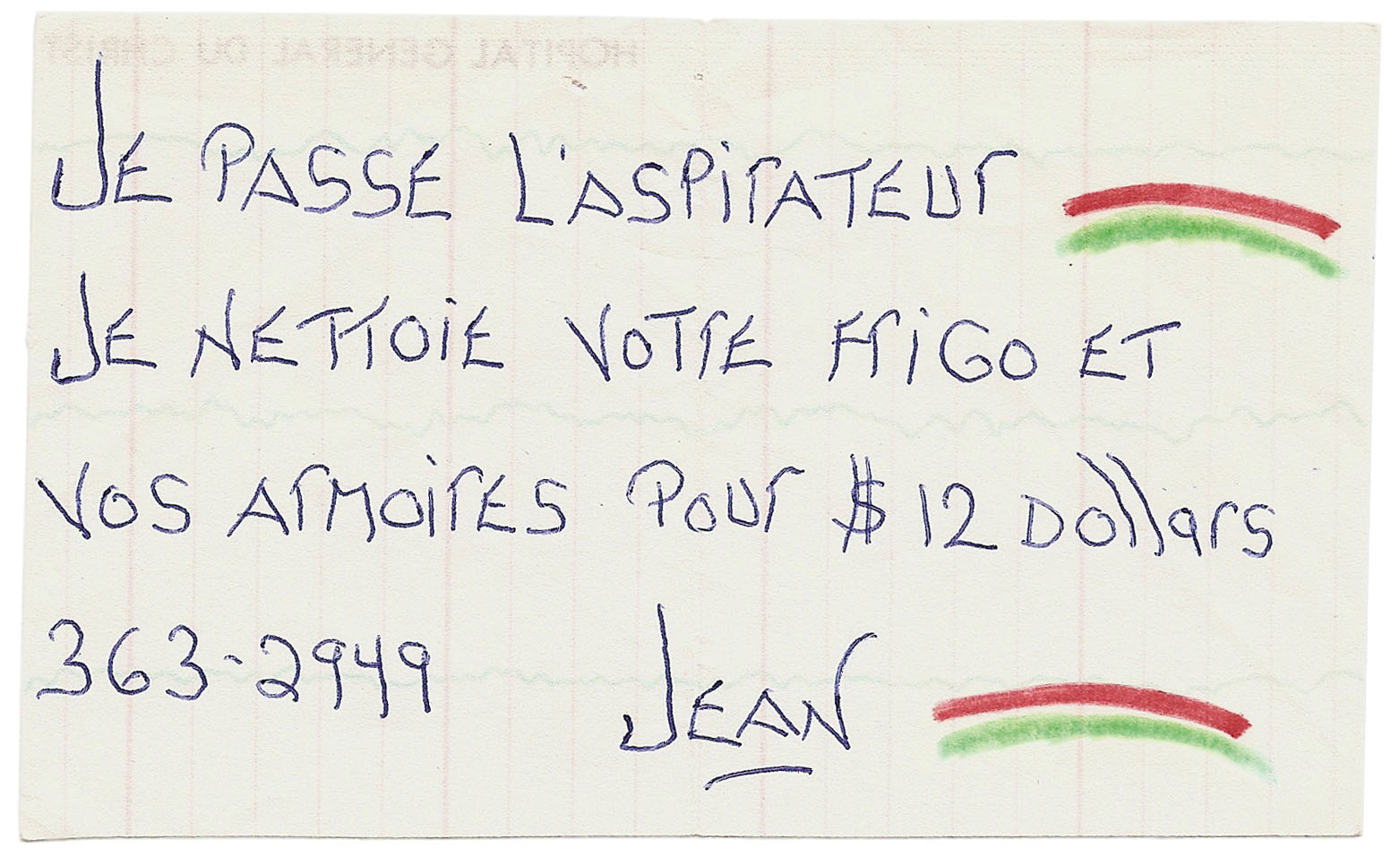

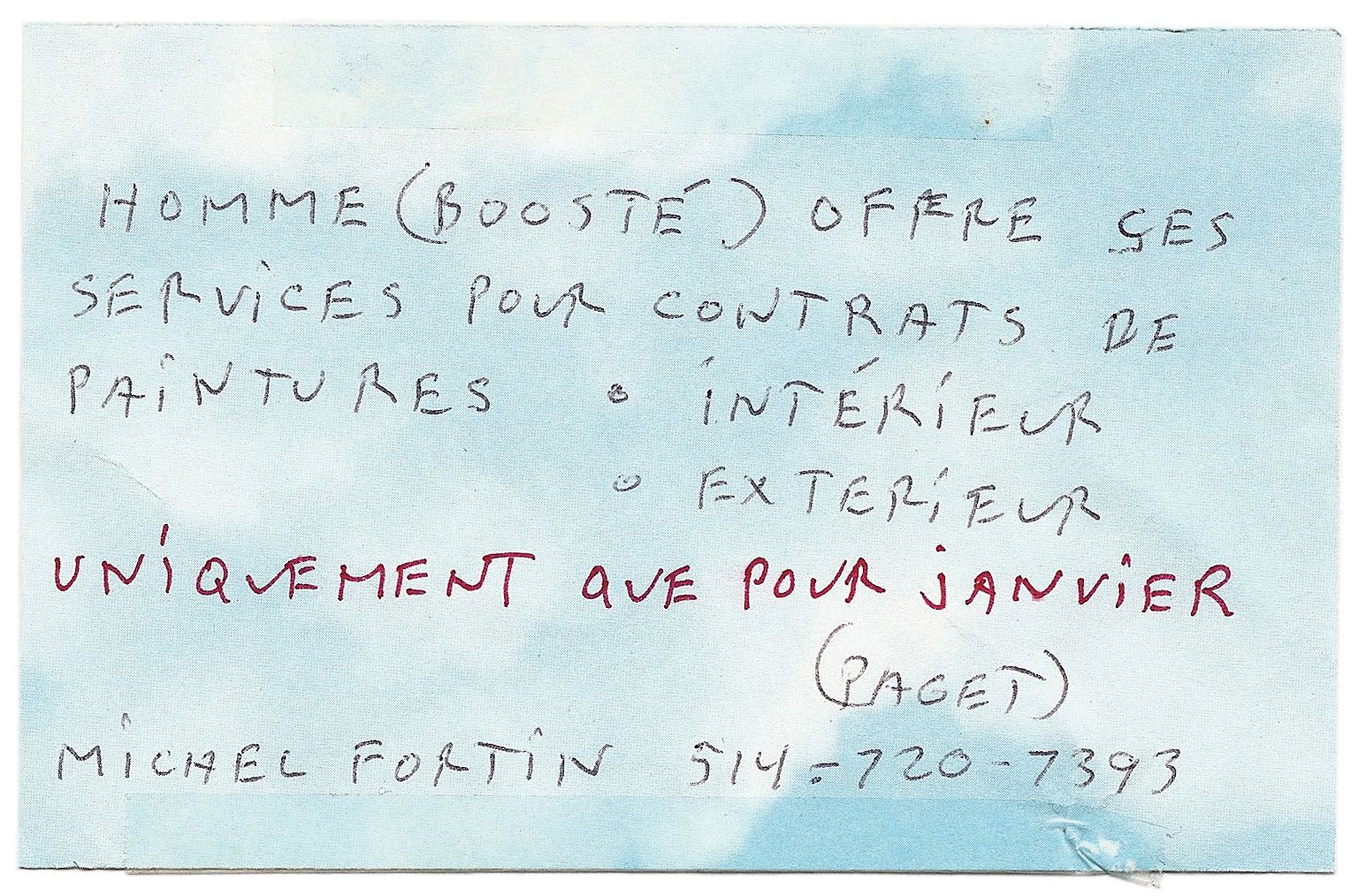

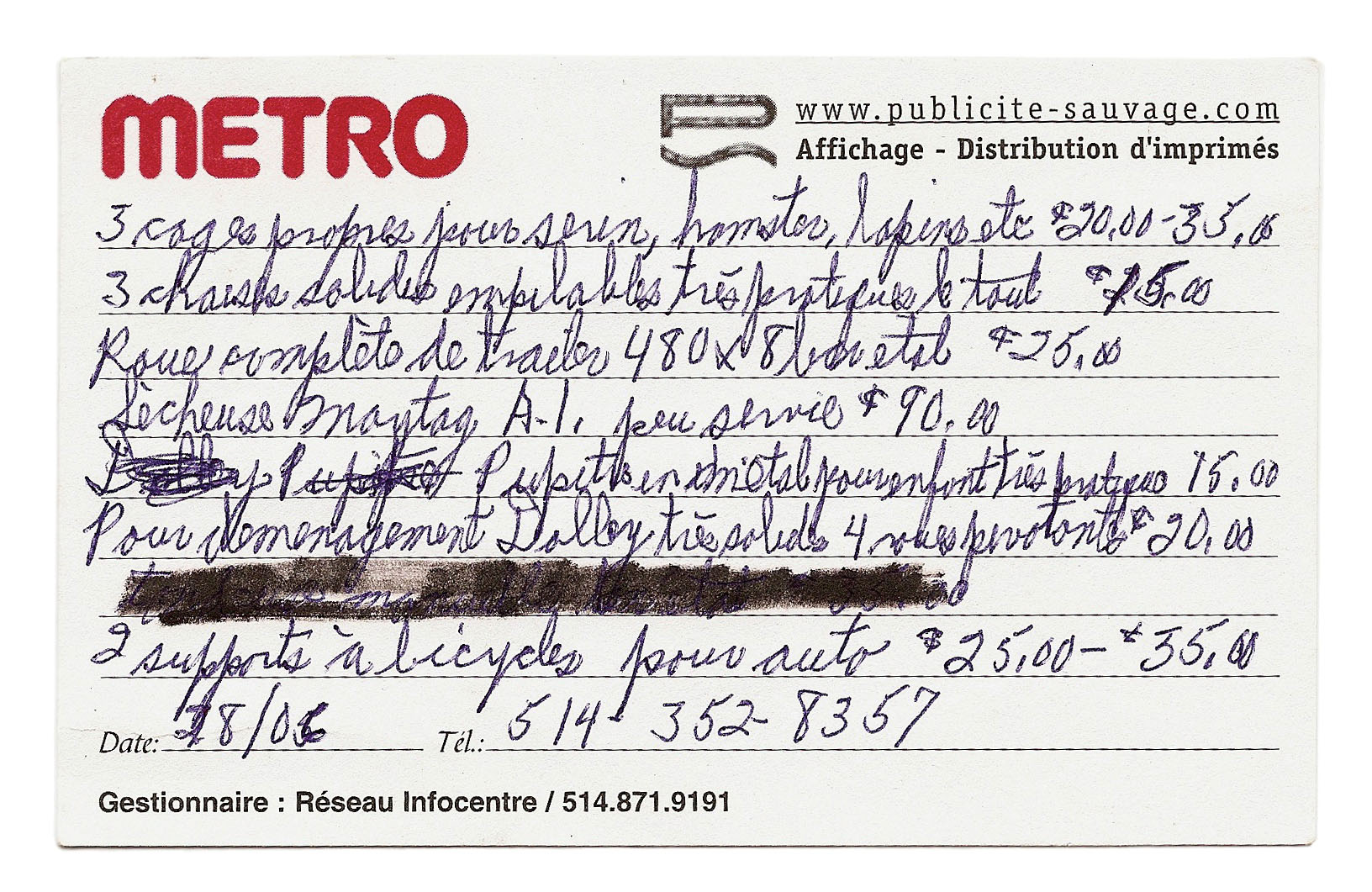

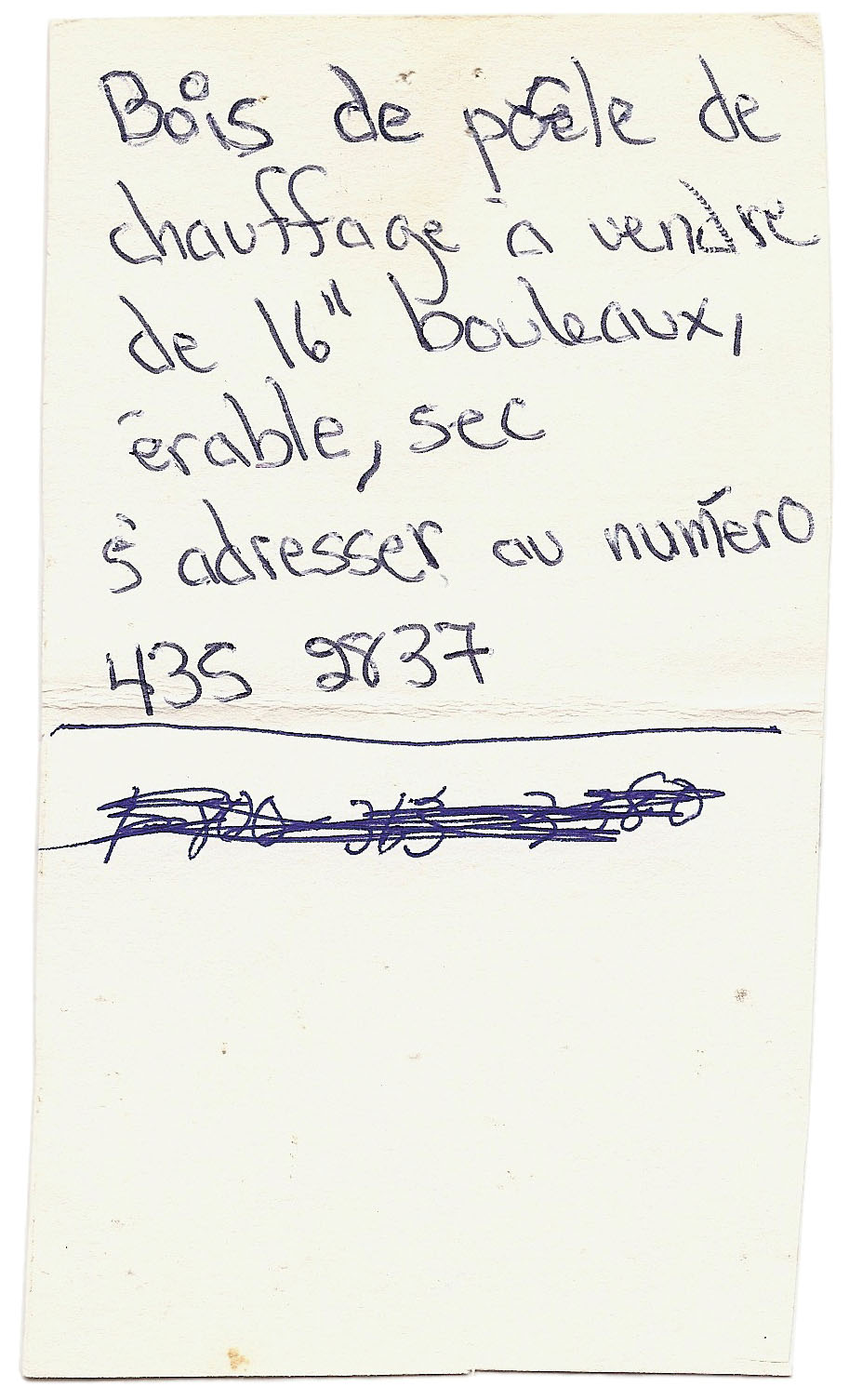

Les petites annonces – Objets poétiques et design vernaculaire, 2001-2009.

Photos: Marc-Antoine K. Phaneuf

Two other works presented as collections generate the same equivocal feeling: Les petites annonces – Objets poétiques et vernaculaires and, in the literary field, the collection Téléthons de la grande surface, both of which the artist connects to the aesthetic of the ready-made. Les petites annonces was presented for the first time at the Centre Clark in 2009. The work is made up of three bulletin boards covered with real, pinned-up ads recuperated by the artist for their “syntactical breakdowns, spelling errors or their ‘simply pathetic’ presentation.”9 9 - Exhibition text: http://www.clarkplaza.org/. Faced with each piece of paper, the viewer-reader imagines a portrait of its author: sometimes smiling, sometimes feeling pity for those reduced to expressing themselves in this way. As to the poetry collection, published in 2008 by Les éditions Le Quartanier, it is formed of numerous lists in which a subjective linking of ideas blurs popular culture, elite culture and daily life to lay out the deliquescent corners of the artist’s black humour. For MAKP, the words compiled under thematic titles — “List of Famous Couples,” “List of People Living in HoMa,” “List of Dead Sports Teams,” “List of Seminal Works of Contemporary Art,” etc. — are ready-mades. In fact, references, citations, names or titles of works are “literary objects” that already exist, the meaning of which the author alters and inserts into a new context, that of the list, forcing unexpected relationships. In these works it is the capacity of collected objects to act as creators of fictions10 10 - Interview with the artist, October 5, 2010. that fascinates the artist, a posture well outlined by Henri Cueco in Le collectionneur de collections when he wrote “the pretext for storytelling is one of the pleasures of the collector.”11 11 - Henri Cueco, Le collectionneur de collections (Paris: Seuil, 1995), 45. And if we succeed in understanding certain allusions in these literary collections, several others escape us — a characteristic that makes of the lists real collections in the sense Baudrillard understands, which is to say subjective systems definitively returning to the subject, the collector.

Thus, Marc-Antoine K. Phaneuf’s Collection de trophées, Les petites annonces and Téléthons de la grande surface clearly speak to us of the current obsession that makes appearances our main preoccupation. An obsession deriving from the process of self-fashioning, or the type of relationship we maintain with our objects (material and literary) and, especially, from the symbolic value we lend them; all are called on to play an important role. Moreover, MAKP doesn’t hesitate to deride this process, as he derides the status of the Artist, the Collector and the Dandy — those upper-case titles (myths?) that are always, definitively, illusions or mirages to feed and torment all those who dream of greatness.

[Translated from the French by Peter Dubé]