Photo : Phillip Maisel, permission de | courtesy of the artist & Kadist Art Foundation

Where religious practices have long been forcibly repressed, they generally return with a vengeance through the dynamic described by Montesquieu, who advocated tolerance for that very reason: “The principle is that every religion which is repressed becomes repressive itself.”1 1 - Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, trans. and ed. by Anne M. Cohler, Basia Carolyn Miller, and Harold Samuel Stone (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), book 25, chapter 9. Worse still, prohibitions against specific gestures (such as Montesquieu’s example of dancing on a crucifix) may suggest the idea to those who had never thought of it. The more despotic the ban, the stronger the backlash.

The oft-forgotten case of Russia goes right to the heart of the issue. The Soviet regime had banished the Orthodox religion, deemed (rightly) to be allied with the tsars: anyone who has seen the films of Sergei Eisenstein will recall the smoky and monstrously silhouetted apparitions of the popes, enveloping the people in a fog with their censers, followed by the people’s destruction of tsarist and religious symbols. Today the Church is making a comeback, and, with the state’s restitution of assets to various religious institutions in 2010,2 2 - On the role of the Orthodox Church in shaping a post-Soviet national identity, see Alexandre Verkhovski, “Religion et ‘idée nationale’ dans la Russie de Poutine,” Les cahiers Russie (Paris: CERI-Sciences-Po, 2006). On the restitution of assets to the Orthodox Church and its consequences, see Denis Babitchenko, “Quand l’État lâche ses joyaux: La Sainte Russie privatisée,” Courrier international (March 11, 2010). it is set to play both an economic and a structural role in the new Russian identity.

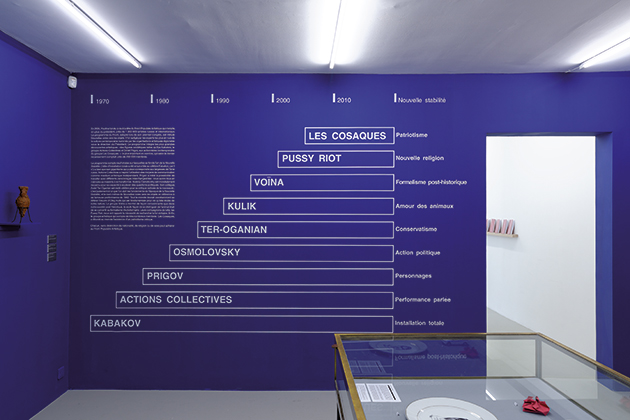

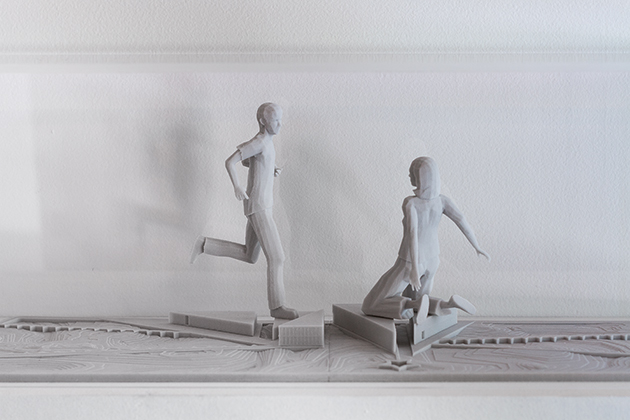

Vue d’exposition, M.I.R.: Polite guests from the future, Kadist Art Foundation, San Francisco, 2014.

Photo : Phillip Maisel, permission de l’artiste & Kadist Art Foundation

“In Germany, one sees people from the dregs of society condemned to death for having danced on the crucifix. Again, punishment creates the crime. Where the crime isn’t punished, who would dream of committing it? A girl who gets it into her head that it is an act of desperation to dance on a crucifix falls into some despair and goes home to dance on a crucifix.” – Montesquieu, a passage in the manuscript excised from the final draft of The Spirit of the Laws.3 3 - (Our translation).

In his installation titled M.I.R.: New Paths to the Objects/Polite Guests from the Future,4 4 - The exhibition’s first subtitle, New Paths to the Objects, was used for the version presented at the Kadist Art Foundation in Paris, January 18 to March 30, 2014; the second, Polite Guests from the Future, was given to the slightly different version presented at the Kadist Art Foundation in San Francisco, July 9 to August 23, 2014. the young Muscovite artist Arseniy Zhilyaev imagines the consequences of this issue by means of a speculative fiction that sketches a sociopolitical portrait of his country in 2020. He does so by creating the galleries of a museum of the future, the M.I.R. (a Russian acronym for “Museum of Russian History”), devoted to this future’s chief artist: Vladimir Putin. The leader has now become a performance artist embracing the artistic heritage of Oleg Kulik and Pussy Riot and, above all, is a follower of a new religion coalescing all the aspirations of the Russian people. The first gallery, the Red Room, as if establishing the foundation of this future society, is wholly devoted to this religion, which arose from a meteorite strike in Chelyabinsk (in the Urals) to become the official religion. As a metaphor for the power of the Orthodox Church, along with what the artist calls “the phenomenon of pop religiosity” — religious practices as they are formed in the media and on the ]Web5 5 - From an email exchange between the author and the artist, August 2014. — it embodies and intermingles conformism and the quest for salvation, naiveté and hope, kitsch and truth.

The sacred body of the angel of Prehistory, 4 500 00 Av. J.-C., exhibition detail, M.I.R.: Polite Guests From The Future, Kadist Art Foundation, San Francisco, 2014.

Photo : Phillip Maisel, courtesy of the artist & Kadist Art Foundation

A SCI-FI RELIGION

Produced on two occasions — for the exhibition the Kadist Art Foundation hosted in Paris and the one presented by the organization in San Francisco — the Red Room is in each case “an epigraph and a key to the whole exhibition.”6 6 - Ibid. It is the point of entry for the fiction the artist has invented, the bifurcation between the real and the imaginary. Its subtitle is, in fact, “The Pillars of the State System: The Formation of Russia in the Prehistoric Period,”7 7 - Silvia Franceschini, Boris Groys, and Arseniy Zhilyaev, Arseniy Zhilyaev. M.I.R.: New Paths to the Objects, exhibition catalogue (Paris: Kadist Art Foundation, 2014), 8. as if, for the artist, religion was the most powerful factor in Russia’s evolution, its founding principle, which it was incumbent on us to examine. The Red Room is the gateway into the exhibition space.

The room is painted red (inevitably recalling the communist legacy) and on its walls are sparingly presented a few pieces created by the artist from real documents. For everything in the exhibition plays on the tenuous ambiguity of truth and falsehood. At the centre, a pillar, also painted red, serves as a support for showcasing a small object that turns out to be a meteorite. As we further explore Zhilyaev’s project, we learn that the object, a real meteorite (though found in Chile, not Russia), forms the basis of a new and quite real religion from which Zhilyaev has extrapolated his own. Rather fantastical in its own right, this actual religion becomes a means to invent a delirious future — and a nearly plausible one at that.

M.I.R .: Contemporary Art and national culture, exhibition view, M.I.R.: New paths to the objects, Kadist Art Foundation, Paris, 2014.

Photo : Aurélien Mole, courtesy of the artist & Kadist Art Foundation

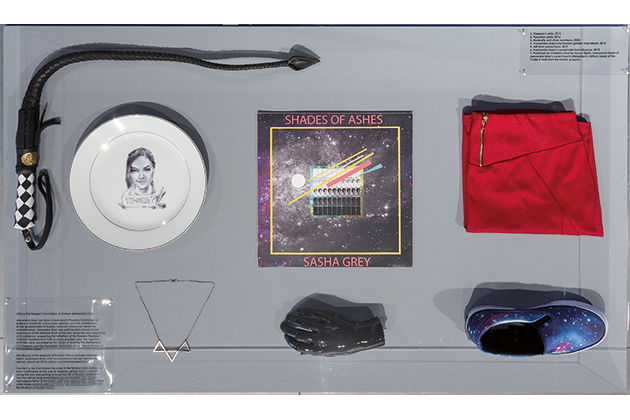

Gifts to the people’s commissar of culture, Aleksandra Grey, 2013-2020, exhibition detail, M.I.R.: polite guests from the future, Kadist Art Foundation, San Francisco, 2014.

Photo : Phillip Maisel, courtesy of the artist & Kadist Art Foundation

This near future is presented in the next two galleries. The Blue Room is devoted to the new activities of the Russian president, who became an artist after his conversion to the new religion. Here too, fiction is grounded in reality. In 2009, Putin made a painting for a charity sale (which was a great success, the painting having sold for 37 million roubles, or almost US$1 million). “He really applied himself, painting it on his own in less than half an hour. He must have been deeply moved, though he didn’t show it,”8 8 - Quoted in Courrier international (January 22, 2009), www.courrierinternational.com/article/2009/01/22/vladimir-poutine-1952-artiste-peintre (our translation). said the gallery sales rep. A copy of the painting is in fact on display in the exhibition. As for other works of Putin the artist, these consist of performances and photographs, official or taken from Russian magazines and re-captioned by Zhilyaev. One, for instance, showing Putin on a tiger hunt, is presented in the Blue Room as a wildlife-preservation action.

The third and last gallery of the Paris exhibition, the White Room, is articulated around the reorganization of the public space consecrating this new Russian society. Its style, however, harks back to Soviet realism, including a gigantic sculpture representing the “defenders of Russian independence,” rendered both in the form of a scale model and as a performance periodically presented in the exhibition space by a couple playing giant biorobots — in other words, “living sculptures.” This particularity connects the room with the science fiction narrative, as it refers quite specifically to a sci-fi novel by the title of Les statues vivantes (“the living statues” — included in a wall display along with city-planning documents).9 9 - Max André Rayjean, Les statues vivantes (Paris: Éditions Fleuve noir, 1972). In short, the new religion is the starting point for a science-fiction story.

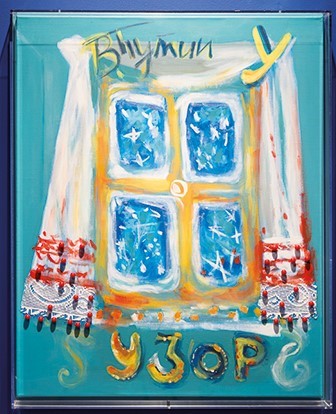

Pattern on the frozen window, 2009, exhibition detail, M.I.R.: New paths to the objects, Kadist Art Foundation, 2014.

Photo : Aurélien Mole, courtesy of the artist & Kadist Art Foundation

“Becoming a Meteorite”10 10 - Max André Rayjean, Les statues vivantes (Paris: Éditions Fleuve noir, 1972).

Presiding over the middle of the Red Room, then, is a real meteorite (from Chile), representing a small fragment of the one that fell in a lake in the Urals near the town of Chelyabinsk, on February 15, 2013. Initially weighing around 10,000 tons, the Chelyabinsk meteorite was one of the largest objects to drop from the sky, triggering shock waves worthy of a nuclear blast and thus producing considerable damage. So extraordinary was the event that it instigated a cult-like following, “the Church of Chelyabinsk Meteorite,” whose members declared, after the fact, that they had predicted the date and place of impact.

Indeed, according to the followers of this religion, the meteorite struck not by accident but in order to bring messages to humans, as its surface is covered with writings that reveal fundamental truths, such as the meaning of existence and new tablets of laws to update those of Moses. All this is explained in a video titled Birth of a Star, projected on the wall facing the meteorite; dated 2020, it is actually excerpted directly from a show on Russian public TV, in which we see the new religion’s guru, Andrey Breyva (real name, Andrey Breivichko), expound its gospel. Breyva appears on the lakeshore accompanied by his acolytes, as they pray for the meteorite’s safety during the salvaging operation. They say that without their presence, the meteorite would sustain irreparable harm. Also presented are projects for building a futurist cathedral to house and venerate the meteorite once it is extracted from the lake.

Photo : Aurélien Mole, courtesy of the artist & Kadist Art Foundation

Fascinated by the video document’s ambiguity, Zhilyaev chose to display it unaltered but for the addition of English and French subtitles, while emphasizing — without denigrating — the outrageous interpretation of reality proposed by the religion’s followers. In his view, this kind of reporting is in line with the history of Russian culture: a desire to instil hope through a denial of reality; state propaganda of the Soviet era being merely a particular instance in an ongoing tradition. In the video, the guru states that “no esoteric school has the slightest doubt that the spiritual renaissance will occur in Russia.” Inviting himself to usurp the main role in this great enterprise, he nonetheless points out the Russian people’s abiding need for “spiritual renaissance,” manifest throughout the media today. This is where Zhilyaev explains his concept of “pop religiosity,” a phenomenon that he notices everywhere around him: “I’m interested in the phenomenon of pop religiosity/spirituality that fills the Internet and everyday life, especially in Russia. It is a very naive, but also a very honest, desire for the truth.”11 11 - Email exchange with the artist, August 2014. This is why his artistic stance is both critical and compassionate: all one can do is decry the fantasies of the meteorite religion while also recognizing that it reflects a real and sincere hope for a better life. As a truth-bearing lie, it embodies a state of mind governed by the marriage of truth and falsehood, an issue the artist explores throughout his installation.

New Religion and Orthodoxy

In Zhilyaev’s proposed fiction, the new religion contaminates both the Russian state, by way of its president, a fervent convert, and the Orthodox Church, which it supplants. In reality, the Orthodox Church plays a predominant role, as it is the most widely practised religion in Russia. Its leaders aligned themselves with Putin during the last elections; as the Moscow correspondent for Le Monde wrote in 2012, “Just before the presidential elections in March, Patriarch Kirill spoke of Vladimir Putin as a ‘divine miracle,’ while declaring his support for the Popular Front, a new pro-Putin party, and urging parishioners to vote for the ‘national [NOTe count=12]leader.’”[/NOTE] 12 - Marie Jégo, “La fusion est totale entre le Kremlin et le Patriarcat,” Le Monde (August 21, 2012) (our translation). The Orthodox Church is staunchly opposed to the new religion, as evinced by the popes interviewed in the aforementioned video, who vehemently decry it as a fraud.

And yet, the Orthodox Church plays a similar role for Russian citizens, who are disoriented after the fall of the Soviet regime, which brought centuries of geopolitical domination to an end. As Alexandre Verkhovski explains in his study of the subject, “After the dismantling of the USSR, Russia had not developed a clear vision of its new identity. President Putin admitted as much himself. Citizens still have difficulty integrating the idea that Russia is a state rather than an empire… This lack of clarity regarding ‘national identity’ allows groups outskirts of power — especially religious organizations — to advance their own proposals.”12 13 - Verkhovski, “Religion,” 3 That is why Zhilyaev brings together the Orthodox Church and the new meteorite religion and places them on an equal footing in some of his works, particularly the three pieces added to the version of the exhibition presented in San Francisco. This version, slightly different from the one in Paris, emphasized the “Russian Cosmic Federation,” the Russian government’s new name, chosen to affirm its role in the conquest of space, both past and to come.

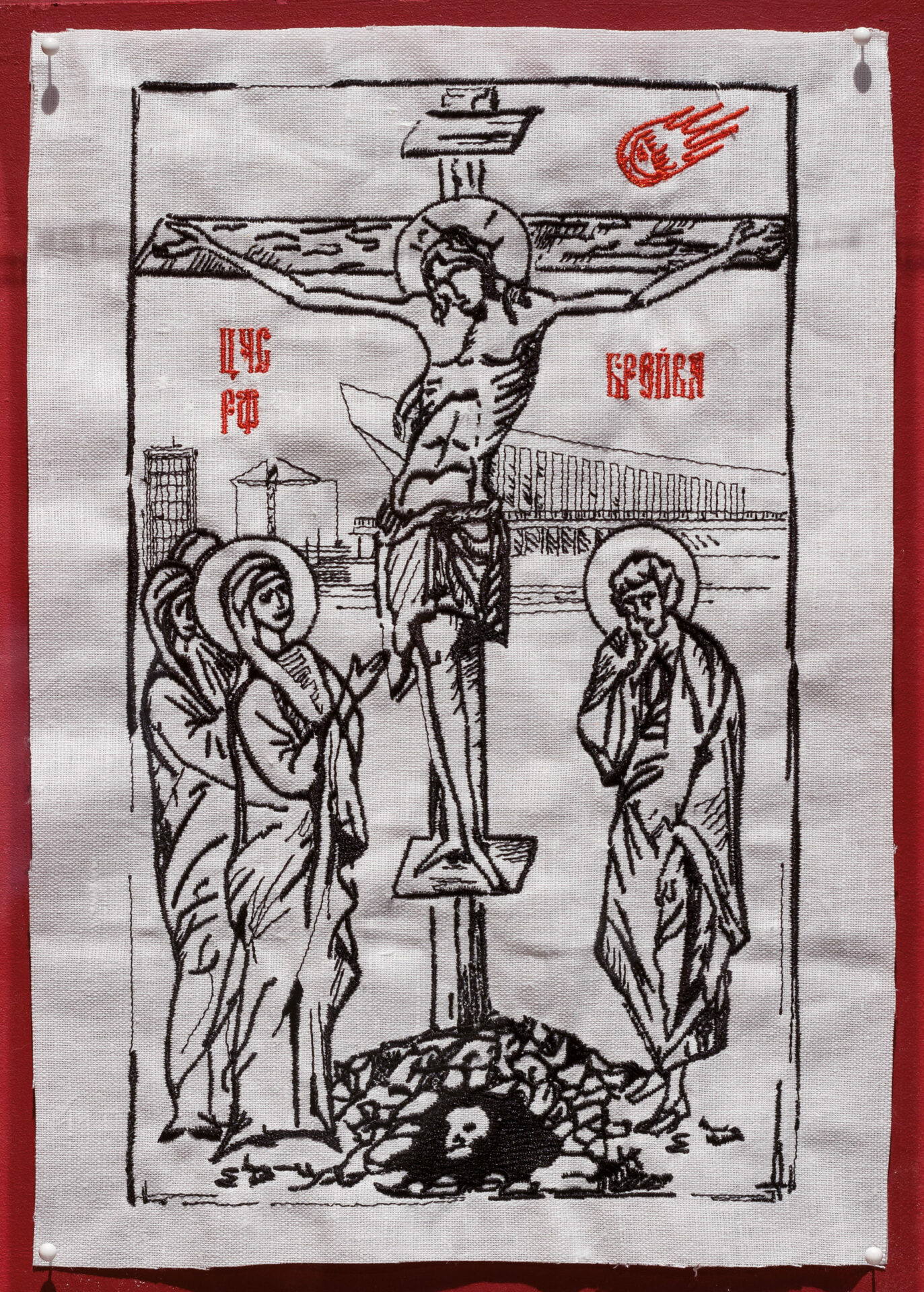

Jesus Chelyabinsky, 2014, Détail de l’exposition | Detail of the exhibition, M.I.R.: Polite Guests from the Future, Kadist art foundation, san francisco, 2014.

Photo : Phillip Maisel, permission de | courtesy of the artist & Kadist Art Foundation

A flag raised outside the exhibition sets the tone from the very beginning. On a graduated blue background meant to imitate the sky, a falling star suggests the meteorite’s arrival on Earth, while in the upper left is a symbol composed of a six-pointed star, a moon, and a Christ figure; Zhilyaev “borrowed” the symbol from the meteorite religion, which used it on its webpage on a Russian social network.13 14 - That page is in fact a great example of pop religiosity: https://vk.com/club55010077 (in Russian). Russia’s official religions meet the new meteorite religion. And then, in the Red Room, Zhilyaev presents an embroidered icon of Christ, which he purchased in an Orthodox shop. The artist added a red orb, initially a rising sun, that he transformed following his inspiration from the February 15 meteorite. In the background is a modernist building inspired by the Chelyabinsk sports complex. Lastly, the same sign has been embroidered on an Orthodox wedding veil. The artist thus effects a syncretism that metaphorically stands for the current spiritual situation in Russia. By combining the Orthodox and Meteorite Churches, he shows the extent to which religion is ubiquitous in Russia. After nearly a century’s prohibition, it resurfaces everywhere and in the most unexpected forms.

With the Red Room, the first room in his museum of the future, which he devotes to religion, Zhilyaev used metaphor and gentle irony to broach a hyper-sensitive topic that touches as much on a residual nationalism as on personal aspiration. He confronts the real by presenting it as science fiction, just as Montesquieu chose fiction and exoticism in his Persian Letters to come to grips with religion in his own time.

Translated from the French by Ron Ross