Photo: Scott Massey

“A fluid territory,” “concealing the horizon,” “anchored outside the event”: the slow sequence of these phrases by artist Uriel Orlow, slide-projected in a gallery corner, gives the viewer a hint of the covert transactions and shifting boundaries of life at sea, as explored in this exhibition, the fourth in curator Cate Rimmer’s vast project of six exhibitions on the sea. The Charles H. Scott Gallery has hosted the different chapters of the series intermittently since 2011, in a way that has foregrounded Rimmer’s creative and performative method of curating. For instance, the three-year length of the series evokes the long commitments of historical sea voyages — Rimmer has cited the three-year voyage of Moby Dick as an influence — and the gallery’s location on Granville Island reminds the viewer of the influence of the sea in Vancouver’s history as a port city. Part of Rimmer’s curatorial approach has been to cull artefacts from the nearby Maritime Museum, a method which has contributed to the anthropological slant of this series, bringing archival objects to light in, at turns, scientifically exhaustive and lyrically riddled narratives. Exhibitions have thus provided contextual threads to such events as the disappearance at sea of artist Bas Jan Ader and yachtsman Donald Crowhurst, who both went missing on solo voyages in 1968.

The fourth chapter distinguishes itself from the series, however, through its examination of the sea as a crucial but forgotten space of globalization and political conflict. These questions are explored through a film essay charting the flow of global trade in port cities, a historical collection of images contextualizing the centennial of the Suez Canal, and a video installation exploring ethical conflicts in the isolation of a cargo ship.

The Forgotten Space (2010), a collaboration between Noël Burch and Allan Sekula, charts the flow of labour patterns in the shipping industry, focusing on three port cities: Hong Kong, Rotterdam, and Bilbao. The invisibility of maritime trade and the complicity of state legislation with the deregulation of its labour, are detailed in the film through a peripatetic voice-over narration, which through a series of interviews and portraits of cities, exposes the economies in which regimes of exploitation can covertly thrive. The narrator thus divulges the enormity of what is at stake: “nine-tenth of world commerce goes through the sea,” through “100,000 invisible ships and one-and-a-half million invisible seafarers.” The collection of perspectives from these workers thereby emphasizes the discrepancy between the invisibility of a maritime labour force and its prominence on the global stage, with the vulnerability of being sidelined in the wake of deregulation.

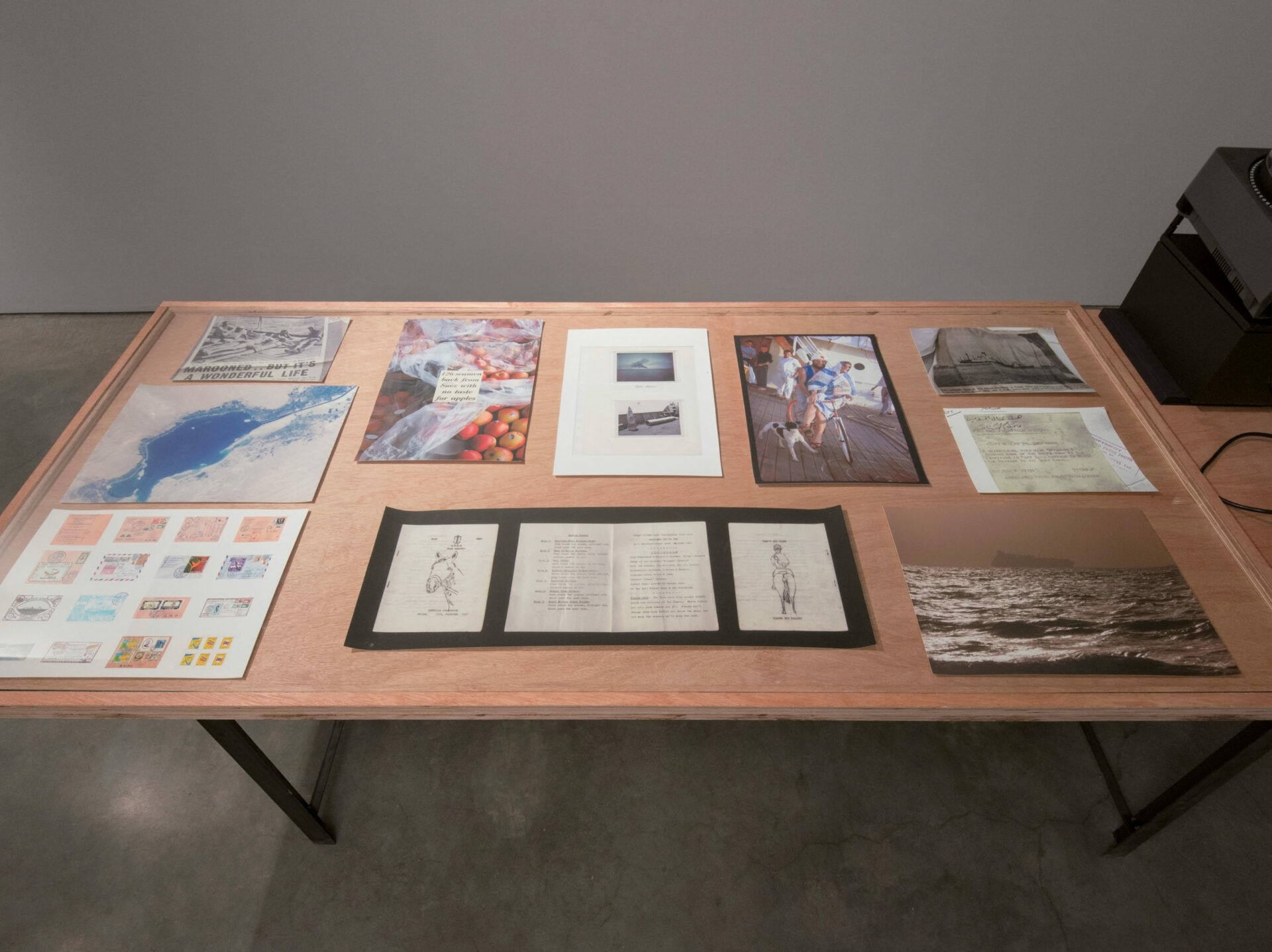

In an exhibition accompanying the film essay, Sekula presents an installation of photographs documenting his voyage aboard the Global Mariner, a ship that travelled to different ports across the world between 1998 and 2000, carrying an exhibition detailing the conditions of workers in the shipping industry. Sekula’s installation presents itself as a kind of museological display with artefacts facetiously exposing the romanticization and mythologies that can undermine a critical reading of sea trade, which is echoed formally in the balance between the photojournalistic style of the photographs and the selection of folkloric and humoristic print reproductions presented alongside them. The installation Flags of Convenience displays several small national flags blown by a tabletop fan, as if plucked from a badly ventilated souvenir shop. The selection of its handful of flags in fact refers to a phenomenon in the shipping industry, whereby nation states offer international ships the opportunity of registering in their waters to escape international labour regulations and provide subpar wages for seafaring labourers.

Ship of fools, 1999-2010.

Photo : Scott Massey

As the narrator of The Forgotten Space reminds us, the shipping container — now a ubiquitous unit for international trade — has made cargo anonymous and secretive. It is this form of maritime commerce, prone in all ways to speculation, which Stan Douglas develops in his film installation Journey into Fear (2001). The film’s narrative is largely structured around two interior scenes of dialogue between a supercargo, Möller, and the ship’s pilot, Graham, which are framed by two shorter scenes presenting outdoor views of the ship. Douglas has constructed the overall narrative as a machine, giving the impression of infinite possibilities in dialogue from a limited number of settings. The two scenes of verbal exchange between Möller and Graham have been synchronized to five parallel dialogue tracks, so that with the recurring settings only the audio changes, giving the characters a kind of dubbed speech justifying the same movements in different ways. Through the interweaving of different audio tracks within select scenes, the film can run for more than six days without repeating itself. These dialogues are framed as ethical debates while referencing historical shifts in international trade over the last decades, such as the fluctuating value of gold or oil. While Graham tries to ensure that her ship safely reaches its destination, Möller tries to delay the ship’s arrival at its port in order to reap benefits from a subsequent $75-million devaluation in the cargo company’s stock value. Möller cynically tries to convince Graham of the tangible benefits of his proposition by claiming to emblematize the boldness required of a risk economy.

The artist has built Journey Into Fear on the pillars of crucial filmic and literary sources: its screenplay has one timeline derived from two namesake thriller films (one from 1942 and one from 1975), both based on a novel by Eric Ambler, and four from The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade, a novel by Herman Melville (1857). In addressing the setting of The Confidence-Man, Douglas has observed that “the story is set in a place where people may briefly assume fictive identities . . . and in an era when relations between people could for the first time be converted into monetary relations.”1 1 - Stan Douglas, Journey Into Fear (London: Serpentine Gallery, 2002), 137. It is this interchangeability that is also evoked through Douglas’ method, reshuffling both his own material and that of his sources to explore how the discussion of economic and ethical questions can evolve in the isolation of the sea. The use of these sources also charts a course historically, from industrialization to the oil crisis of the early seventies, where patterns of regulation in international trade were themselves reinvented.

Exploring the recent history of international relations through another lens, Uriel Orlow delves into its fictionalization through a panoply of artefacts and historical allusions, from photographs to slide show displays, videos, and drawings. He specifically explores tensions between the documentary form and the romanticization of history by focusing on the sixties and seventies in the region of the Suez Canal.

For instance, in a display case he presents newspaper clippings and historical artefacts documenting the conflict of the Six-Day War between Israel, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan in June 1967. As a result of the conflict, fifteen ships were left stranded in the Yellow Sea until 1975. These ships became known as the “yellow fleet” because of the sand accumulated on their decks. Orlow also presents stamps issued from the ships, as well as various ephemera related to this period and the region for the viewer to slowly piece together a historical and geographical context. The aesthetic of the archival is echoed in video and photographic documentation, in which idle play under the sun belies the highly sensitive nature of its geo-political context.

Through an exploration of the historical shifts in international relations, the three artists of the exhibition probe into how life at sea is represented, and critically examine obscured aspects in the dynamics of international trade. These depictions of sociality at sea, at the fringes of the jurisdiction of nation states and beyond conventional moral compasses, question the familiar representations of the sea as a sublime space of risk and escape, pointing instead towards how it is inscribed in the sublime of globalization with its attendant effects of social fragmentation, misrepresentation, and invisibility.