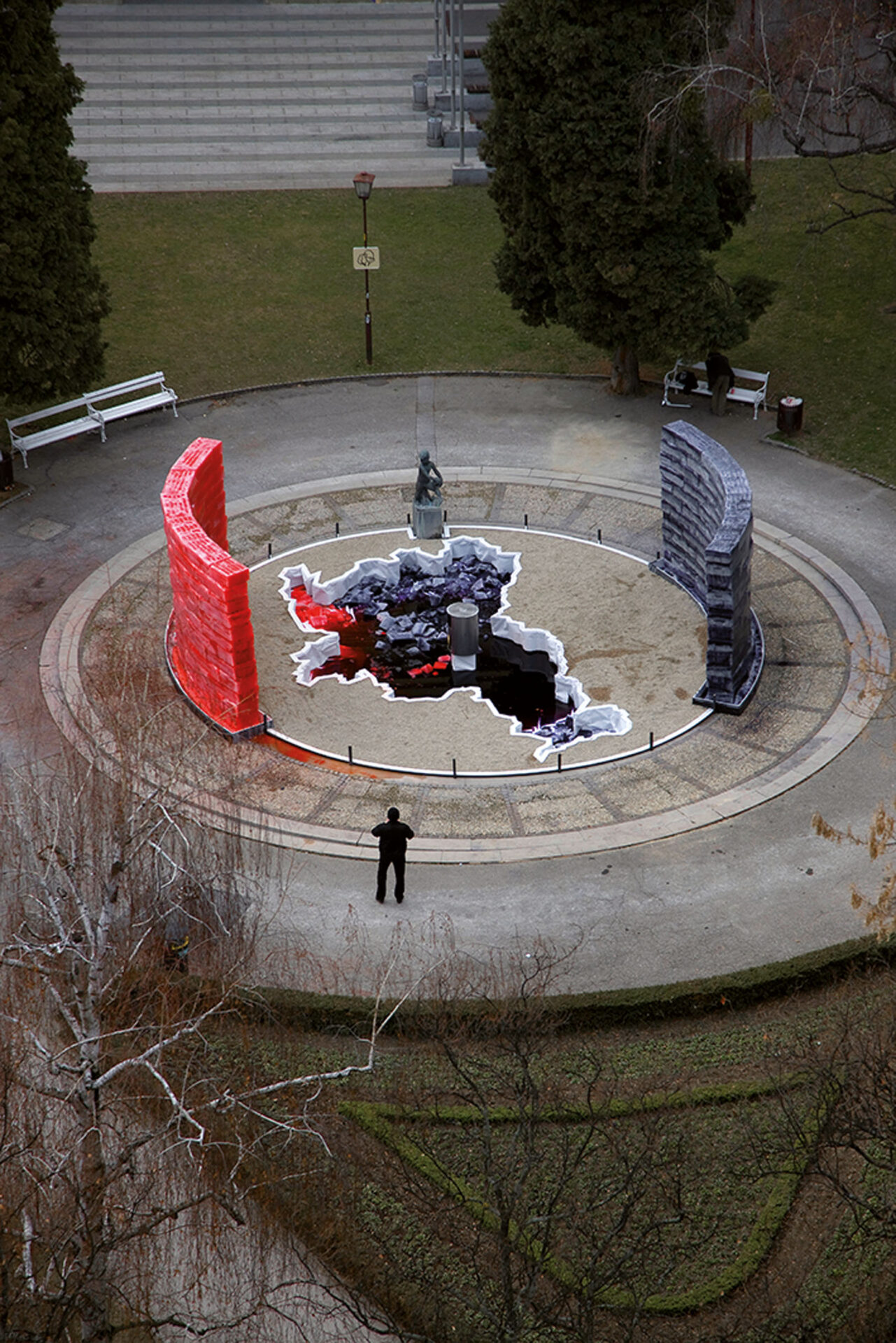

The Wailing Wall, Novo Mesto, Slovénie, 2011.

photo : Borut Peterlin, © Maska

The importance of bodily participation in performance art is an emancipatory experience for modern spectators, and paramount in the work of Allan Kaprow, the artist now recognized as the main inventor of modern happenings in the late 1950s. Kaprow’s performance The Fluids (1968) is about the perceptions of the voluntary participants (and much more, of course) while they were building the rectangular ice walls. The volunteers’ agency was certainly defined in advance, yet this does not diminish its truth value. Their decision to be personally engaged in the project was a source of their emancipation in an otherwise temporarily set artistic “community” that was not necessarily an act of one individual’s perception. Community, not individuality, was in the forefront of Kaprow’s ice projects.

Almost a half century later, one artist took the individuality of the spectators of the performances deadly seriously. Janez Janša1 1 - The artist’s original name was Emil Hrvatin. He changed his name to Janez Janša together with two other artists, Davide Grasi and Žiga Kariž, as part of the artistic project of joining the Slovenian Democratic Party. Its political leader, Janez Janša, was at that time also the economic liberal-conservative Prime Minister of the Republic of Slovenia. is a leading Slovenian author and director of interdisciplinary performance. His artwork represents one of the ways in which the performing body has been applied in Slovenian theatre in the past two decades: the theatrical spectacle in the body.

Janša’s obsession with the idea of a wall made of slowly melting ice bricks as a metaphor for the relation between perception, emotions, and memory is evident; the performative installation The Wailing Wall2 2 - The project took place as an international collaboration between Anton Podbevšek Theatre Novo Mesto, Maska Ljubljana (Slovenia), and Huis en Festival a/d Werf, Utrecht (Netherlands) on 17 March 2011 in Novo Mesto, and 25 – 28 May 2011, in Utrecht, Netherlands. is not his last such artwork. Moreover, the work is a continuation, or a kind of supplement, to his performative installation from 1998, Camillo Memo 4.0: The Cabinet of Memories — A Donating Tears Session, which was recognized as “a hybrid performance action, a tableau vivant installation, or simply a theatre play for one visitor, user, participant at a time.”3 3 - Marina Gržinić, “The Cabinet of Memories,” in Janez Janša and Maja Murnik eds. The Wailing Wall (Ljubljana, Novo Mesto: Maska – APT, 2011), 59.

Photos : Borut Peterlin, © Maska

In 2012, a similar performative installation, The Wailing Walls, was built in Maribor, another Slovenian city. Two semicircular walls, one red and the other black, made of ice blocks confronting each other, were left to slowly melt. The water from each wall was directed to the pond in the centre of the circle defined by the walls. The pond was designed in the shape of Slovenia. The walls symbolized two prevailing Slovenian political ideologies — left and right — which in the political struggle for domination slowly, but inevitably, contaminate and poison Slovenian society.

Janša’s artwork The Wailing Wall is hardly a performance in the traditional sense. There are no performers involved, and certainly people who decide to become a part of the spectacle cannot be considered spectators, not even in a manner similar to those in post-dramatic theatre. The Wailing Wall is more like a performative installation. It presupposes a rather high level of voluntary involvement by the spectators.

photos : Borut Peterlin, © Maska

The Wailing Wall consists of three separate cabinets, also called lachrymatories, constructed inside a local public library in Novo Mesto, and a wall made of large ice blocks built outside the library. The cabinets are small boxes named the Cabinet of Individual Memory, the Cabinet of Collective Memory, and the Cabinet of Physical Memory. On entering the lachrymatories, the spectator is equipped with specially designed glasses in which to collect her own tears. The spectator enters either the Cabinet of Individual Memory or the Cabinet of Collective Memory. In the former there is only a mirror on the wall, in which the spectator, while sitting on a low bench, can watch herself trying to remember something that would provoke tears in her eyes. In the latter, the spectator finds a TV set and a collection of films. The spectator can pick out a film of her choosing. Not every film in the collection is sad or tragic — even humorous sketches may bring tears to the eyes. If the spectator is neither touched by movie nor by private memories, she may enter the Cabinet of Physical Memory, where her body is exposed to certain tear-provoking substances, such as onions. Depending on which cabinet is the most simulative environment in which to shed tears, the spectator is rewarded with a gold, silver or bronze certificate.

The second part of Janša’s installation takes place behind the public library. A wall, approximately 6.5 metres long and 2.5 metres high (no record of the precise dimensions exists) and consisting of seventy-seven huge ice bricks is built in the field. A red carpet leads the spectator to the ice wall, on which, as on a screen, the instructional text is projected: “Take a slip of paper and write down a wish or a thought you would like to be fulfilled. Put the slip of paper into a hole in the wall. Then return the pencil to the table.” The spectators left all kind of messages in the wall, from profane and quotidian (I want a Mercedes-Benz. Right away!) to more humane and profound (The wall of separation that causes all tears and pain in the world is built by our own prate. Ignoring this, we hope the walls of ice will dissolve by themselves). Over several weeks the ice wall slowly melts until there is no trace of it at all.

Photos : Damjan Švarc

Janša’s inspiration for The Wailing Wall was the concept of the panoptic intimate theatre “where the terminal individual is at the same time performer and spectator,” that is, the spectActor, as posited by Giullio Camillo (1480 — 1544).4 4 - Emil Hrvatin, “Terminal SpectActor,” Janus, 2001, 62. One characteristic of Janša’s work is his contested and unique use of the principal concepts of cultural studies.5 5 - Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator, (New York: Verso, 2009), 17. Living in the world of a performative society, an individual is an isolated miniature society, to a high degree separated and alienated from other individuals, translated into the symbolic language of performance art, “every spectator is already an actor in her story; every actor, every man of action, is the spectator in the same story.”6 6 - Luk Van Den Dries, “Tearjerkers and Mindgames,” Theater Forum, 2003, 3 – 11.

Janša’s interest in the spectator’s performing body has a long history. He was one of less than a dozen spectators who had the privilege of attending Dragan Živadinov’s Biomechanics Noordung, performed in weightlessness in 1999 in an Ilyushin 76 aircraft, departing from Russian Star City near Moscow. Janša depicts his experience as a spectator as alienation from his body due to losing bodily control in weightlessness. The spectators were forced to develop a new relationship with their own bodies to be fully able to take an active part in the performance. “The true ‘drama,’” says Janša, “was the drama of the subjects’ fight for control over their bodies.”7 7 - Emil Hrvatin, “Biomechanics in Weightlessness,” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, 2002, 102 – 07.

His performative artworks represent one of the ways in which the performing body has been applied in Slovenian theatre and performances in the past two decades:“This change can be noticed at the very turn of the century . . . in which Janez Janša shifts the locus of theatre into a spectator’s body.”8 8 - Barbara Orel, “Cabinets of Tears: The Art of Memory, Configuration of Perception and Digital Technologies,” in Janez Janša and Maja Murnik eds. The Wailing Wall (Ljubljana, Novo Mesto: Maska APT, 2011), 37-47. See also Blaž Lukan, “Body in Context: Slovene Theatre at the End of Transition,” in Dennis Barnett and Arthur Skelton eds. Theatre and Performance in Eastern Europe: Changing Scene (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2008), 169 – 179. Being in the state of the body-home,9 9 - See Tomaž Krpič, “Medical Performances: The Politics of Body-Home,” PAJ — A Journal of Performance and Art, 2010, 167 — 175. spectActors of The Wailing Wall developed two different sensual relations: private and public. Though not physically weightless, they still had to fight for control over their bodies. In the cabinets, the spectActor develops a private perception triggered by private, collective, or physical memories; standing in front of the ice wall, the spectActor develops public perception as she most likely does not stand there alone. As such, The Wailing Wall is an excellent illustration of identical/auto-sensual bodily performing relations,where the spectator becomes one with the performer. The spectActor is the subject, and at the same time, the producer of her own auto-sensual practices.