photo : courtoisie | courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery

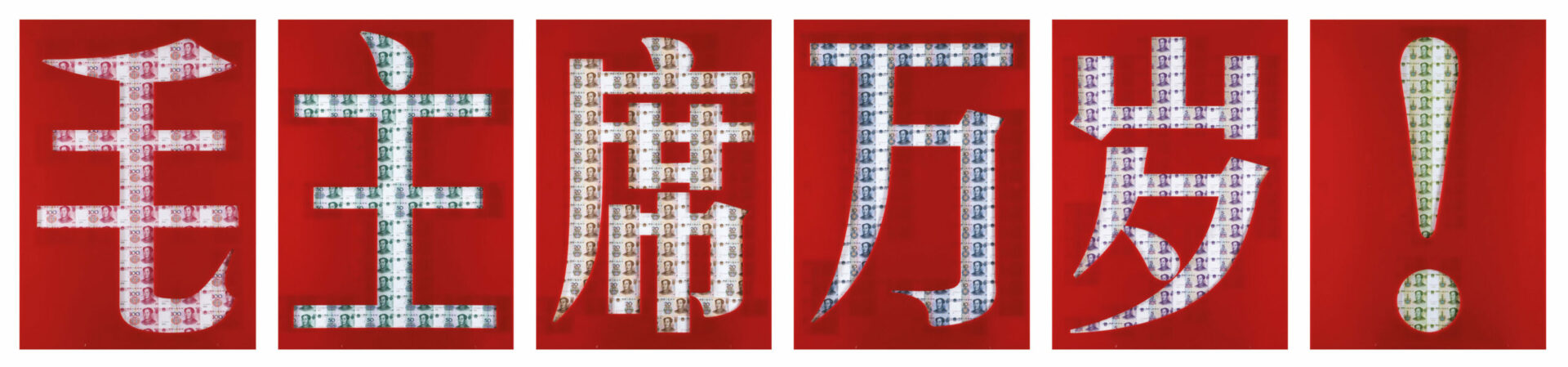

As an original founder of the avant-garde art Stars in 1979 now actively involved in the development of the 798 Art District in Beijing, Huang Rui is one of the leading figures of the Chinese contemporary art scene. He is a highly socially engaged artist who incorporates numerous and complex political and historical references into his works. Decidedly conceptual works like “Chairman Mao 10,000 RMB” or “Chai-na/China,” for instance, reflects the paradoxes posed by the ideological collision between socialism and capitalism up to the present day in contemporary China.

Huang Rui’s body of work is intrinsically tied to memory, yet manages to avoid the usual memory trap of bitterness and nostalgia. Most importantly perhaps, he also successfully keeps a sharp political stance without falling into cynicism. Irony on cultural stage was one of the most important phenomena in China of 1990s, as illustrated by the commercial success of “political pop,” “cynical realism” and the like. Although undoubtedly refreshing in a Chinese context, the post-modern game of artsy quoting to which numerous contemporary artists have committed themselves in the recent years is certainly not as subversive as one often tends to believe. In this regard, the Chinese political situation, and Huang Rui’s work in particular, offers a great opportunity to reconsider the relation between art production and the power structures in which it is involved. In the end, is irony not the cardinal virtue of existential liberalism, but the nervous tic of those too timid to hold true convictions?

From the Stars

Contemporary Chinese art is still largely identified in the West with the work of one generation of artists—those who launched the new art scene in the mid 1980s to the mid 1990s. This “political pop” is still widely considered as the defining style of contemporary Chinese art, and synonymous with the avant-garde. Huang Rui’s artistic itinerary contrasts sharply with the advent of political pop and commercial culture in China. Political pop bears witness to the death of utopianism and thus provides us with crucial insights into China’s post-Tiananmen cynical and apathetic mindset. On the contrary, Huang Rui’s artistic background is intimately related to the birth of avant-garde art in China in 1979 and the growth of the democratic movement through the 1980s. The genealogy of the avant-garde and the democratic movement thus gives us an interesting look from the inside at what would later culminate into the events of 1989.

Huang Rui (b.1952) worked as a farmer in Inner Mongolia from 1968 to 1975 and then in a leather factory in Beijing until 1979. In 1978 he published the most important post-Cultural Revolution magazine, Jian Tian (Today). But what really marks the entrance of Huang Rui on the avant-garde scene is his participation with the first group of “nonconformist” Chinese artists, Xing-Xing (The Stars). The group was formed by different artists who met thanks to the Beijing Spring (1979-80), a period when emerged the Democracy Movement, an elite youth group that pursued ideals of spiritual freedom and intellectual independence. “We chose the name Stars,” Wang Keping recalls, “because at that time we were the only lights shining in an endless night and also because stars, seen from afar, seem so small, yet can prove to be huge planets.” According to Ma Desheng, another member of the group, “Every artist is a star. Even great artists are stars from the cosmic point of view. We called our group ‘The Stars’ in order to emphasize our individuality. This was directed at the drab uniformity of the Cultural Revolution.” The Stars became famous in 1979 by hanging their politically “incorrect” paintings and sculptures on the railings outside the National Museum of Fine Arts in Beijing. This act of defiance, the first unauthorized exhibition of Chinese art since 1949, set the stage for an era of liberation for future artists.

The Stars continued to face harsh official criticism and in 1983, due to political pressure, the group disbanded voluntarily and the majority of members left China. Huang Rui moved to Japan in 1984, where he broadened his scope from painting to photography, installation and performance art. He will not participate in an exhibition in China until 1992.

photos : courtoisie | courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery

Chai-na/China

I discovered Huang Rui during my visit at 798 Daishanzi art district in Beijing in June 2006, right after the international exhibition “Beijing/background” (굇쑴교쒼).1 1 - For an extended overview of Huang Rui’s work, see Huang Rui (Beijing: Timezone 8 and Thinking Hands, 2006). As I entered his gallery, I was immediately struck by an impression of massive vacuity. This immense space was all white except for one very high wall, entirely painted with Communist China red. A few artworks were carefully disposed in the room, almost exclusively related to China’s communist legacy. The entire gallery appeared as a gigantic resonance chamber of the Maoist era, with an ascetic, conceptual and subtractive void as its central element.

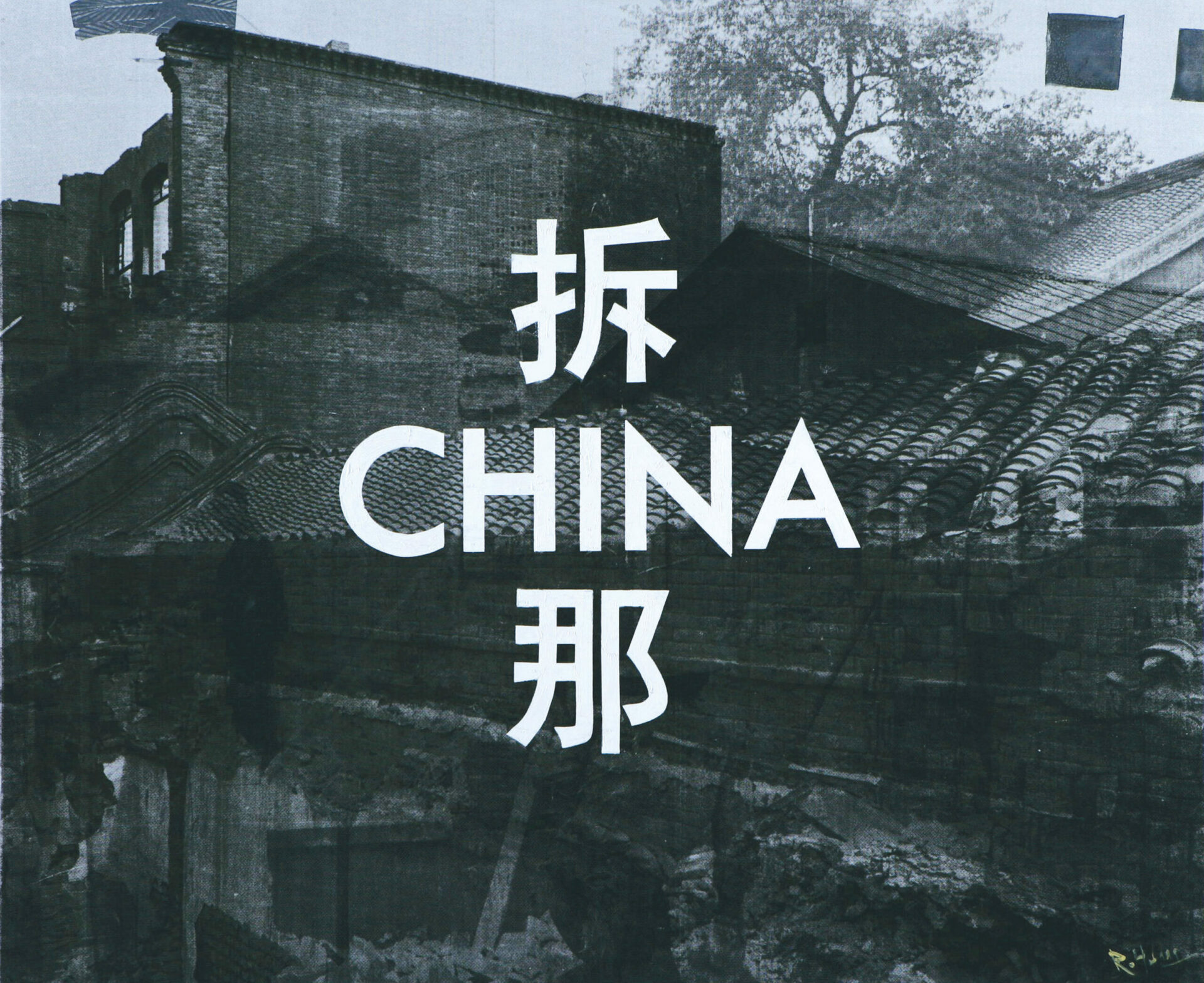

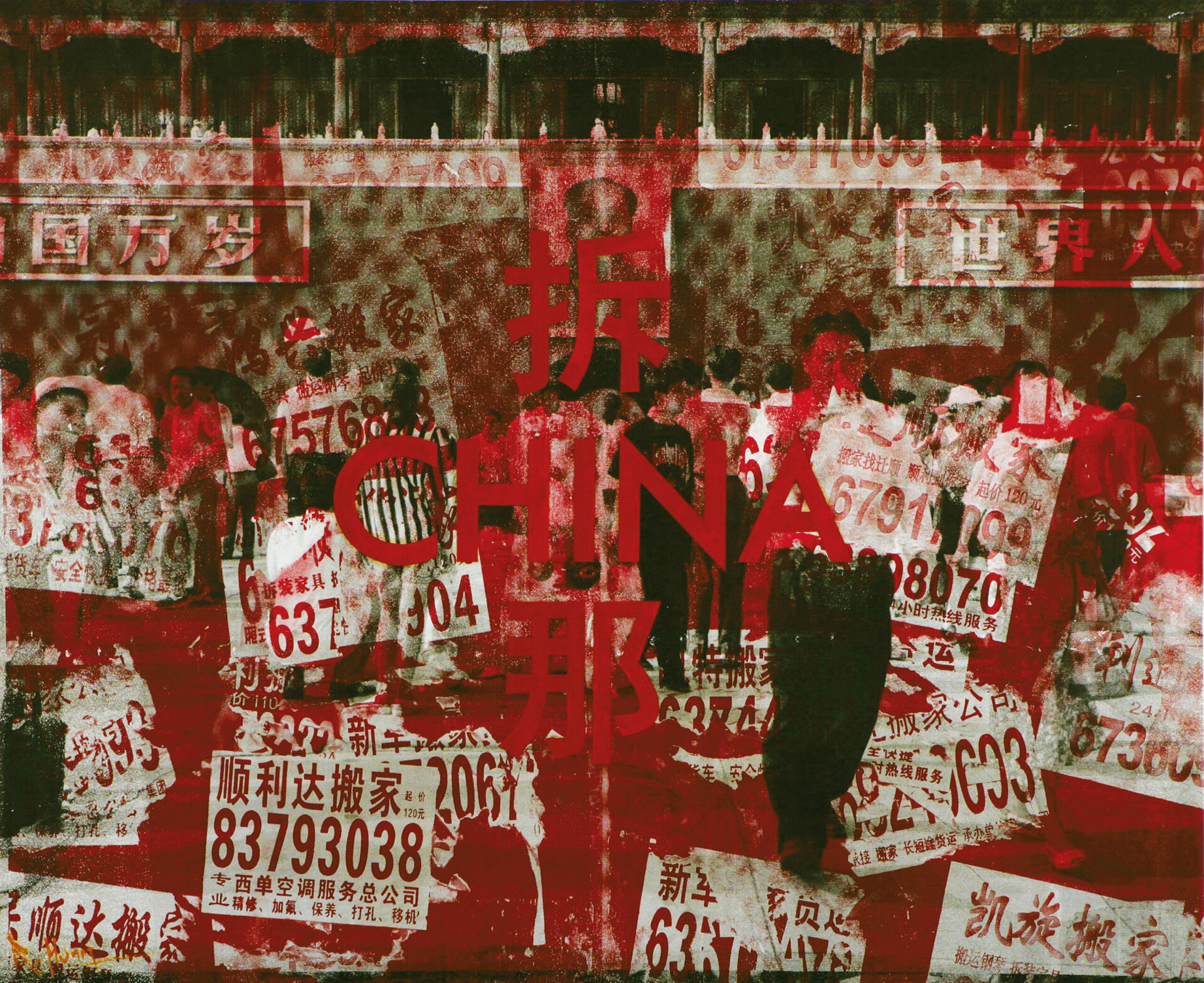

Huang Rui’s work engages in a radical fashion with China’s history, which in turn permits him to develop powerful insights into China’s current situation. In many of his works, the focus is clearly set on the destruction, not only of tradition, but of the socialist legacy as well. Chai-na/China is a series of seven triptychs, totalizing twenty-one paintings. On these large canvases, the English word “China” is juxtaposed with Chinese characters that read as “chai-na,” literally “demolish here.” In the background, are photos of Beijing that bear witness to a city in the midst of urban and social mutations. The character “Chai”” (뀔), which has been painted on countless walls around Beijing and every other Chinese city, is the dominant symbol of the destruction of the old to make way for the new as the country re-sculpts itself at hyper-speed. Wang Jingsong, another Beijing artist, also worked on this theme and created a T-shirt on which is written the following: “‘chai’—it seems like a crucial dividing line, on the left there is destruction, on the right construction, destruction of the old, construction of the new, as if the old doesn’t go, the new cannot come. ‘Chai’s’ meaning immediately emerges, but what exactly is the new, and what exactly is the old?” Wang Jingsong bears witness to the often blindly-lead rush for modernization under capitalist pressure in contemporary China, offering a valuable starting point to open debates on this complex issue.

In Huang Rui’s Chai-na/China painting series, it is interesting to notice that he is not only concerned with architectural heritage but with social justice as well. Hence the paintings figuring two migrant workers, a smiling child or stickers add for movers. Huang Rui’s critical stance about China’s often brutal urban and economical development is further developed in another work based again on a clever use of the possibilities of Chinese language. In 뷘疳랙꼿 (heng shu fa cai), a big tree is suspended in the air, horizontally. Its roots are wrapped into a golden bag, on which is written the work’s title in various directions, thus forming a square with the characters. The English title, Regardless of Wealth, doesn’t quite catch the subtle meaning conveyed by the inscription in Chinese, which would literally mean something like “laid-down tree/make fortune.” The crucial word here is the first one, 뷘, heng. Like so many words in Chinese, it possesses a particularly rich semantic field. First, “heng” suggests horizontality, something that is put transversally, east-west ward. It also refers to the idea of laying something flat. We can see thus how it applies perfectly to the position of the tree in the work. But “heng” also conveys a moral signification. Applied to a human being’s behaviour, “heng” means egoistic, mean, brutal, unfair. It is also commonly applied to the idea of making money, hence “hengcai”, 뷘꼿, ill-gotten gains, or heng facai, 뷘랙꼿, get rich by foul means. In an incredibly concise and powerful way, Huang Rui deplores the inconsiderate exploitation of natural resources, and thus takes a strong stance in regard to the current development of China’s economy and its ecological consequences.

Huang Rui’s use of the Chinese language’s poetic ambiguity reaches virtuosity level in his Deng Xiaoping Woman. Like Guillaume Appolinaire’s calligrams, Huang Rui depicts a feminine figure only using characters. The head is formed with the slogan 寧몸櫓懃,좃몸샘굶듐, literally “one center, two foundations,” but refers to the formula “one country, two systems” (寧벌좃齡). This catch-sentence was used by Deng Xiaoping in the context of the reunification with Hong Kong, as a promise that nothing would change in the relation between the two political entities for the next fifty years. There is another work by Huang Rui precisely entitled “One Country Two Systems,” which is composed of a thousand everyday consumer products placed on fifty shelves, each one bearing the label “one country, two systems, remains unchanged for fifty years.” To give an idea of the importance of this famous political statement, it is also at the origin of Wong Kar-Wai’s last movie, 2046, precisely the year when this promise will come to an end.

Huang Rui, Chai-na_China-3, 2005.

photo s : courtoisie | courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery & Huang Rui

Let’s move back to Deng Xiaoping’s Woman. The mouth of the woman is formed with the word 婁, zhua, which can mean “grab,” “take control” or “seize,” her breast with the words 좃庫, liang tou, “the two ends,” a coma stands for its bellybutton, and her vagina is drawn with 던櫓쇌, dai zhong jian, “reach the centre.” This piece is arguably the most concise expression of Deng Xiaoping’s pragmatism, echoing his famous “No matter if it is a white cat or a black cat; as long as it can catch mice, it is a good cat” (꼇밗겜챔、붚챔,덥遼일柑앎角봤챔), the catch-phrase that launched the process of economic reforms in the beginning of the 1980s. The multiplicity of meaning of each of the sentences employed in this work and their interplay is just staggering, as it involves a lexicon that is rooted in China’s antiquity and is still in use in today’s political speeches. It is a lexicon that was, according to the tradition, first formulated by Confucius when he edited the history of the State of Lu, the Spring and Autumn Annals, judiciously choosing expressions to describe political actions in moral terms. The use of terms that combine both descriptive and evaluative meanings is what Epstein calls “ideologemes.”2 2 - See Mikhail N. Epstein, After the Future: The Paradoxes of Postmodernism and Contemporary Russian Culture (Amherst: University of Massachussetts Press, 1995). This kind of cryptic and allusive formulation allows the government to “reach for the centre” and maintain its grip on power as it navigates through the tensions and contradictions it is likely to face. With this piece of art, Huang Rui brings us right into the heart of one of the most fascinating aspects of Chinese traditional thought, that is, its essentially strategic conception of power and the immanent philosophy of language that is related to it.3 3 - See Jean-François Billeter, La Chine trois fois muette (Paris:Éditions Allia, 2000), for a very interesting account of the relation between strategy and politics in China. Also, see his refutation of François Jullien’s thesis of China’s “pensée de l’immanence” in Contre François Jullien (Paris:Éditions Allia, 2006).

It is not everybody who becomes like everybody, who makes of everybody a becoming. It requires a lot of ascetism, of sobriety, of creative involution. — Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

Huang Rui’s work is certainly a challenging and demanding one. It is particularly sober and refers to precise historico-political Chinese contexts. Undoubtedly, its minimalist qualities bear influence of his prolonged stay in Japan. Its simplicity is both elegant and imperative, as it obliges us to ruminate every single meaning conveyed. In this rarefied space, it opens way for a delicate itinerary of depuration, a subtractive process that echoes the brutal and revolutionary purges of the communist past, without ever exactly coinciding with it; a deliberate sustain of a minimal difference that allows for a singularity to emerge, on the verge of both socialist heritage and the current triumph of capitalism. In many ways, Chinese collective memory is still deeply impregnated by Mao’s legacy, certainly more than the young generation tends to believe. This is particularly true when we consider the issue of today’s Chinese nationalism. Huang Rui’s work reflects this situation, as he is primarily concerned with the political and cultural forces that shape the Chinese ideoscape. Contrarily to the immense majority of artists who have revisited Mao’s icon with endless replications of his face, Huang has always focused on Mao’s ideas, slogans and the propaganda he implemented. If political pop hardly conceals its not quite assumed nationalist content, inversely, Huang Rui’s treatment of Mao’s legacy is among the few that presages singular becomings that resist the current molarization and overcoding of social life, and not only in China. In his Collected Works of Mao Zedong, arguably the most impenetrable of his work for a non-Chinese audience, Huang Rui replicates the cover of each of the four volumes of this legendary piece of literature. Huang Rui adds to this series a little known fifth volume compiled by Hua Guofeng, and his own sixth volume. For a Chinese person coming across this last piece, the effect is arresting. This very subtle addition is Huang Rui’s ingenious way of drawing a line of flight out of Mao Zedong’s legacy, a line of flight that perhaps can also challenge late capitalism’s closure of history.