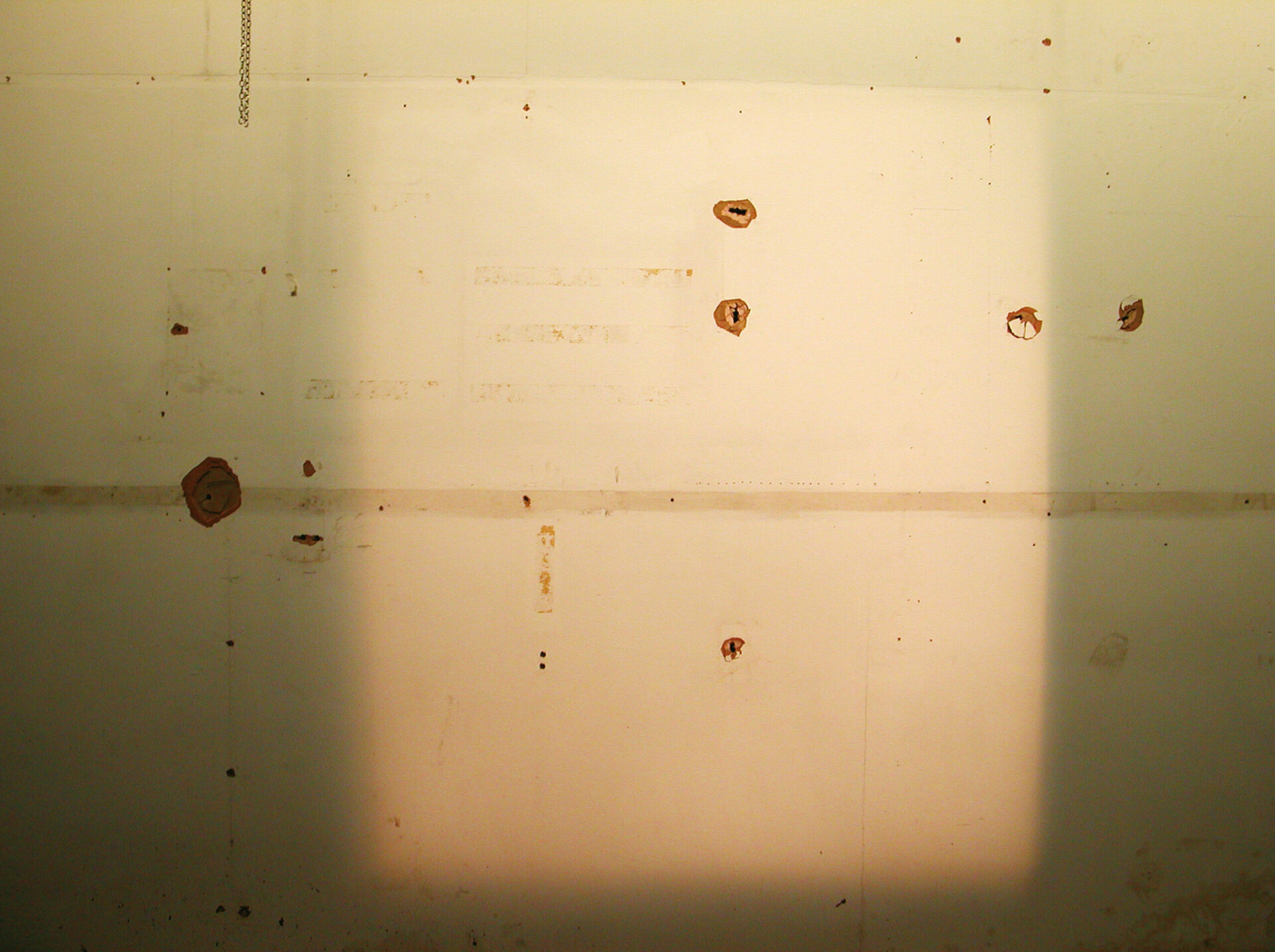

Monstrous Matter

In recent years, tales of assemblages have been the subject of numerous interdisciplinary inquiries. As scientists and humanities researchers alike question preconceived notions of “individual” species, organisms are more accurately understood as nodes in multifaceted networks — networks so intricate that it becomes impossible to distinguish where an organism begins and ends. Beings and matter aren’t whole, they are viscous porosities. The human body is not exempt from this shift in materiality. As Donna Haraway observes, “The human genomes can be found in only about 10 % of all the cells that occupy the mundane space I call my body; the other 90 % of the cells are filled with the genomes of bacteria, fungi, protists, and such… I become an adult human being in company with these tiny messmates. To be one is always to become with many2 2 - Donna J. Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 4..”