As I understand it, a regime is an identifiable system of discourse that controls the sharing of sensory knowledge in a society (Jacques Rancière, Michel Foucault). Art regimes, therefore, define the various normative policies regarding the teaching, production, perception, circulation, and reception of artworks. This line of thought assumes an origin that extends farther back in time than the current debate on cultural appropriation because regimes bring about continuities and ruptures over extended periods.

My personal experience has led me to the notion of the cultural imperative, which also aims to displace an enduring false interpretation: that cultural appropriation can be indiscriminately applied both to minority cultures and to cultures in positions of power. The notion of the cultural imperative allows us to identify the presence of the appropriationist regime through its effects, and the cultural appropriation debate allows us to draw nearer to two of its processes: predation and cultural consumerism.1 1 - Bernard Stiegler defines cultural consumerism as a mode of cultural over-consumption created by a marketing rationale (which, among other things, translates into a constant desire for the new). He states that “the art lover … has slowly but surely been transformed into a cultural consumer.” “Bernard Stiegler : conférence à Paris du 8 sept. 2009,” Dailymotion, video recording (Paris: Tvetoile.net, 2009), 10 min 22 s, www.dailymotion.com/video/xalb2i (our translation).

Although the cultural imperative prevents any fairness by standardizing different cultural systems in an individual’s inner depths, we will perhaps see a utopia of radical dialogue emerge, in the sense that Western regimes will no longer be the authoritative standards for art discourse.

The Cultural Imperative : a Personal Experience

Whereas the word “imperative” means giving an authoritative command to a person or group, as I see it, the French intimation also refers to the adjective “intimate,” something that “generally remains hidden beneath the surface, impervious to external observation, sometimes even to the assessment of the subject itself.”2 Therefore, the cultural imperative (in French, intimation culturelle) is the directive, whether tacit or otherwise, to conform with the cultural canons prescribed by a group in a position of authority and for the commanded subject to metabolize this directive intimately. This definition relates explicitly to my experience of receiving an imperative that remained impenetrable for a long time and that was deeply implanted in my psyche.

Like someone trying to exit an office and comically yet brutally knocking into a glass door, I encountered invisible but painful obstacles in my art history courses from high school to art school. As a descendant of French colonial slaves, I saw myself being taught day after day from a young age that one should appropriate the cultures of the world. “Eddy, it’s a big world out there! I don’t understand why you want to tell us about what’s happening on your own doorstep, right between your toes.” Yet in art history courses, the universality of art looked a lot like a white man’s toes on the sole doorstep of European history. On the one hand, the sacred Eurocentric model was held up as the universal authority, and on the other hand, I was ordered to cherry-pick forms or other symbolic inspirations from “weak cultures,” like mine, that were bereft of artistic talent. While Ingres, Caravaggio, and many others represented the artistic genius of my colonizer, the absence of Afro-Caribbean references in my education implicitly attested to my people’s incompetence in the fine arts.

My cultural imperative stems, therefore, from what decolonial theory calls the coloniality of knowledge — that is, the colonization of my senses and mind. This epistemic and sensory colonialism (based on philosophies of knowledge) forced me to use systems of thought and theoretical frameworks that had not been devised for me. Therefore, the more I foolishly absorbed the notions of my colonizer, the more my acculturation increased. The education that everyone assured me was empty of imperial ideology had forced me to accept the claim that Europe and the West in general held the highest artistic values and that my local culture had weak notions that were only locally significant. Therefore, the cultural imperative gave rise to two movements in me. First, my academic education, conceived by and for the West, led me to a self-denial. Second, the unjust knowledge-power relationship made me kick the productions of my own culture like an old sack of potatoes.

To summarize, let us say that the cultural imperative inherits the “black skin, white mask” syndrome that Frantz Fanon writes about, the “burial of … local cultural originality.”2 2 - Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (London: Pluto Press, 2008), 9. Furthermore, when I use the formal codes and symbolic content that are specific to the West, I do not commit an act of appropriation. I make a more or less successful imitation by responding to the injunctions of an exogenous model that was not intended for an artist who is a descendant of slaves, as one of my 2016 works, JG (égo + dualité),3 3 - The titles of my works are signs from my own emotional alphabet, as I try to extricate myself as much as possible from the dominant discourse illustrates. Conversely, I find it difficult to reappropriate something that comes from my own culture, because the cultural imperative also instils a self-denial. Yet, to quote Aimé Césaire and René Ménil, “We can no longer be parasites on the world. Rather, we need to save it.”4 4 - Aimé Césaire and René Ménil, Tropiques 1 (April 1941): 5. Reissued by the Parisian publisher Jean-Michel Place (1978) (our translation).

Cultural Appropriation Puts a Regime on Public Trial

Sociologists (Eric Fassin, Lawrence W. Levine) define cultural appropriation as an unfair act that consists, for the upholders of a dominant culture, in seizing (without remuneration) minoritized cultural production in order to gain some kind of profit (aesthetic, financial, moral, or other). Although culture clashes of all kinds (wars, annexations, coalitions, and so on) have encouraged countless thefts of objects and cultural appropriations from time immemorial, the current debates on cultural appropriation reveal a confrontation between two main approaches to the question: the position of predation and that of cultural consumerism.

Representing the first approach, the Innu-Algonquin filmmaker André Dudemaine posits that the concept of cultural appropriation effectively indicates “cultural cannibalism.”5 5 - André Dudemaine, “L’appropriation culturelle et les peuples autochtones : Entre protection du patrimoine et liberté de création,” conference held at the Université du Québec à Montréal, April 2018 (our translation). This devouring portrays the predation by one culture of the “cultural fodder” of another culture that doesn’t have the necessary resources to defend itself against the extraction and exploitation of its best cultural resources. Exemplifying the second approach, the African-Québécois philosophy professor Amadou Sadjo Barry believes that art proceeds from an inalienable appropriationist system. During a radio discussion on Robert Lepage’s Kanata,6 6 - Radio-Canada, “Kanata : la question de l’appropriation culturelle est-elle sans issue ?” Pas tous en même temps (April 21, 2019), https://bit.ly/2RGaogL (our translation).he claimed that “without appropriation, we sign the death warrant of art” and that “legitimate appropriations” therefore exist. Although the first approach fits within the sociological definition provided above, the second needs adjusting in order to be reconciled with it. Despite being necessary, doesn’t this second approach also ask me to link appropriation to cultural consumerism? In my particular experience of great cultural injustice, the very root of the transitive verb “appropriate” makes one wonder. In French, the reflexive pronoun added to the verb — “s’approprier” (to appropriate for one’s own use) — expresses the desire and greed for a cultural object that will become personal or collective property. It is therefore possible that the role played by desire in reconciling the question of cultural appropriation gets downplayed. By setting up uneven power relationships, desire pushes very hard to take the best of what the weakest have to offer. As I mentioned earlier in relation to the cultural imperative, my imitation stands in extreme opposition to this desire, between the master culture and the minoritized culture. In a recent article published in Minorit’Art,7 7 - Norman Ajari, “Du désir négrophilique : Arthur Jafa contre l’érotique coloniale de la masculinité,” Minorit’Art 3 (April 2019): 134–143, http://minoritart.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Minoritart_3.3.pdf. philosopher Norman Ajari reminds us that desire and appropriation are at the heart of slavery, the prelude to capitalism.

Although the notions of predation and cultural consumerism may appear to be two major irreconcilable positions, I believe that they are part of a single appropriationist regime, and that the current debate is a kind of public trial of this regime. Such a tribunal challenges one of the normative policies that regulate perceptible exchanges between cultures, at both local and global levels. Yet, the appropriationist regime hasn’t always existed in art — much less so on a global scale.

‘ A [Recherche/Chasse], détail de l’installation | installation detail, 2016.

Photo : Guy L’Heureux, permission de | courtesy of the artist

From an Absent Appropriationist Regime to the Discourse of Formal Predation

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, at a time of “discovery” and colonial expansion, the formal productions of non-Western cultures were considered irrelevant curiosities. The cabinet of curiosities, for instance, speaks volumes about the attitude that led to collecting exotic cultural objects and placing them alongside naturalized plants, animals, and insects. The naturalizing re-semantization of cabinets contributed to making these cultural productions into the expressions of people who were still in the “infancy of art.” Professor Lionel Richard tells us that up to the very end of the nineteenth century in Europe, “no ‘expert’ existed who would dare claim that the statues, masks, and instruments sculpted by ‘exotic’ peoples were also artworks. The eccentrics who prided themselves on asserting this were not taken seriously.”8 8 - Lionel Richard, De l’exotisme aux arts lointains

(Paris: Infolio, 2017), 67 (our translation). Obviously, no Western artist or expert dreamed of making any kind of cultural appropriation whatsoever. So, what happened to cause the regime to be overturned?

In the late nineteenth-century, racialism came under attack by many anthropologists, ethnologists, and writers. Among them, ethnologist Ernst Grosse claimed that despite the “natural state” of Australian Aboriginals, every line of their drawings “betrays an artistic talent.”9 9 - Ernst Grosse, The Beginnings of Art (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1897), 175. As the idea of race gave way, an aesthetic sense began to be attributed to the productions by “primitives.”

Yet the subordinate position of so-called primitive peoples encouraged the pillage of formal riches, since these people were deemed incapable of carrying out the basic discursive processes that could allow them to correctly imagine a work of art. Philosopher Friedrich von Schiller wrote, “To appropriate the object [means] to transfer it from the domain of instinct to its own domain, that of discursive processes.”10 10 - Friedrich von Schiller, “Réflexions détachées sur diverses questions d’esthétique,” OEuvres, vol. 8, trans. A. Régnier (Paris: Librairie Hachette et Cie, 1880), 168 (our translation). He added, with respect to primitive people,11 11 - Whom he calls unsophisticated “savages.” that “in truth, their imagination is susceptible enough to try to represent the infinite sensory universe, but their reason is not independent enough to completely carry out this undertaking.”12 12 - Schiller, “Réflexions,” 169 (our translation). In short, primitive creation lacked the classical Greek system of discourse that would allow it to attain the full status of art.

Many voices therefore advocate for taking possession of the best production of primitives still stuck in the infancy of art. For example, in his 1856 work, The Grammar of Ornament, architect Owen Jones extracted a series of formal resources from the colonies and invited Western artists to do the same by looking at “admirable lesson[s] in composition.”13 13 - Owen Jones, The Grammar of Ornament (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1868), 15. Later on, Lionel Richard reminded us that the official Bulletin published for the Lyon world fair in 1894 advised artists to seize these riches in order to exploit them: “Indigenous art … is not without merit, from which even French art could borrow.”14 14 - Richard, De l’exotisme, 157–158 (our translation).

The discourse of extraction and the exploitation of formal resources is not new: it has been rooted in art since modernism. Unlike borrowings or thefts between cultures, an almost industrial system of formal foraging has been set up with regards to all other cultures. We are well aware of the consequences of this today. And even when we refuse to engage in this discursive possibility, it is impossible to remove the spirit of predation that haunts both the modern era and our own.

For an Equitable Dialogue

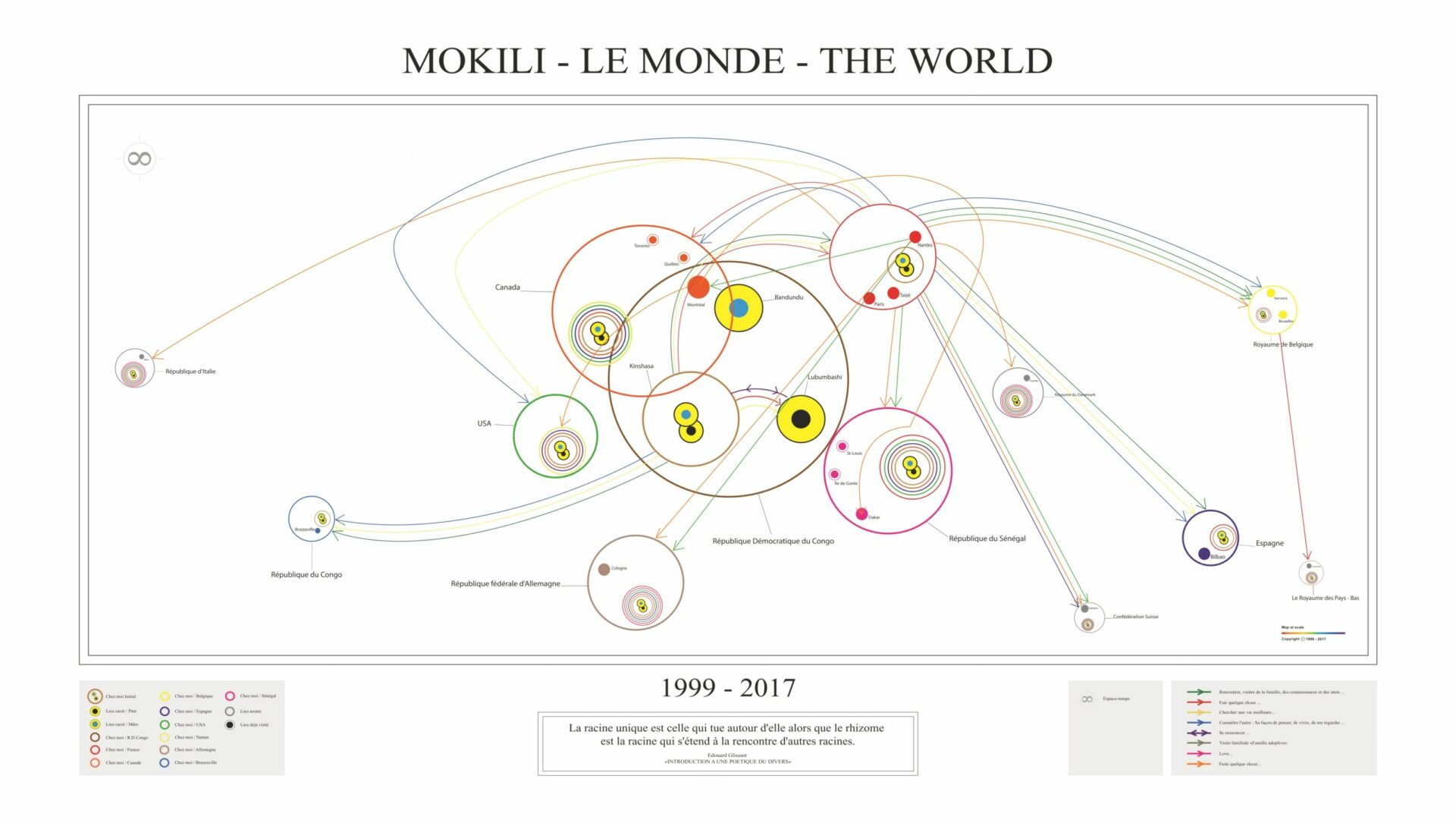

Today, artists on all sides are examining forms of neocolonialism that could be hidden in some of their formal or discursive content. For example, The Chapman Family Collection (2002) by brothers Jake and Dinos Chapman makes a strong critique of contemporary art’s cultural cannibalism in relation to global consumerism. In the Mokili — Le monde — The Map series (1999–2019), Congo-born Québec artist, Moridja Kitenge Banza examines the position of the Other and his own position in art discourse through the journeys that brought him to Québec. Without any irony, he asks whether the maps that he uses to conceptualize the geographical world and the art world are not in fact two discursive instruments that are specific to the West. These artists are indirectly asking a question that is absent from the debate: Where are the discursive regimes of other cultures, and how could we enter into dialogue with them in an equitable manner?

Althought the cultural imperative prevents any fairness by standardizing different cultural systems in an individual’s inner depths, we will perhaps see a utopia of radical dialogue emerge, in the sense that Western regimes will no longer be the authoritative standards for art discourse. I admit that I find it difficult to properly see this emergence, since, like a fish in a fishbowl, my system of thought and my work are used to navigating the current appropriationist regime.

While waiting for this utopia, I struggle to decolonize my own imaginary and re-enchant my gaze made obese by the overconsumption of formal vocabularies of all kinds.

Translated from the French by Oana Avasilichioaei