Photo : Guy L’Heureux, courtesy of the artist

For the 56th Venice Biennale, the Global Art Affairs Foundation invited Guillaume Lachapelle and Simon Bilodeau to participate in the group exhibition Personal Structures – Crossing Borders. Fast becoming one of the most important of the Biennale’s Collateral Events program, this exhibition is the result of a project that Dutch artist Rene Rietmeyer launched in 2002 in order to encourage encounters and exchanges among artists from around the world. The project is ironically named after the emblematic exhibition Primary Structures, held at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1966, during which minimalist artists imposed their credo of an objective art free of any trace of manual labour. Rietmeyer’s initiative instead gives pride of place to artists with distinctly subjective practices and singular approaches. Since 2007, activities in Personal Structures have been articulated around the themes of time, space, and existence. Despite the four symposia devoted to the project — Time (Amsterdam, 2007), Existence (Tokyo, 2008), Space (New York, 2009), and Time – Space – Existence (Venice, 2009) — no specific editorial perspective has emerged.1 1 - Communications related to these symposia are brought together in Personal Structures: TIME – SPACE – EXISTENCE, s.l., Global Art Affairs Foundation, 2009. In 2011, after exhibitions and symposia held in Asia, Europe, and North America, the project put down roots in Venice. Among the artists participating in the event this year are Carl Andre, Bruce Barber, Daniel Buren, herman de vries, Richard Long, Robert Mangold, François Morellet, Hermann Nitsch, Yoko Ono, and Lawrence Weiner. This year, as with previous editions, the exhibition will be held at Palazzo Bembo, where Lachapelle and Bilodeau will share a space in which they intend to showcase a few of their recent productions revolving around the Personal Structures themes.

Modelling a World

For a dozen years or so, Lachapelle has been producing miniatures characterized by an attention to detail, highly precise renditions, and meticulous execution. First giving form to small figures and objects, their iconography sometimes tinged by the surreal, he then dwelled on the representation of architectural elements or the creation of truly autonomous worlds. The use of 3D printing also lends his works an impersonal and disquieting quality. He constantly strives to take advantage of the exhibition set-up, often playing with light sources and various display devices.

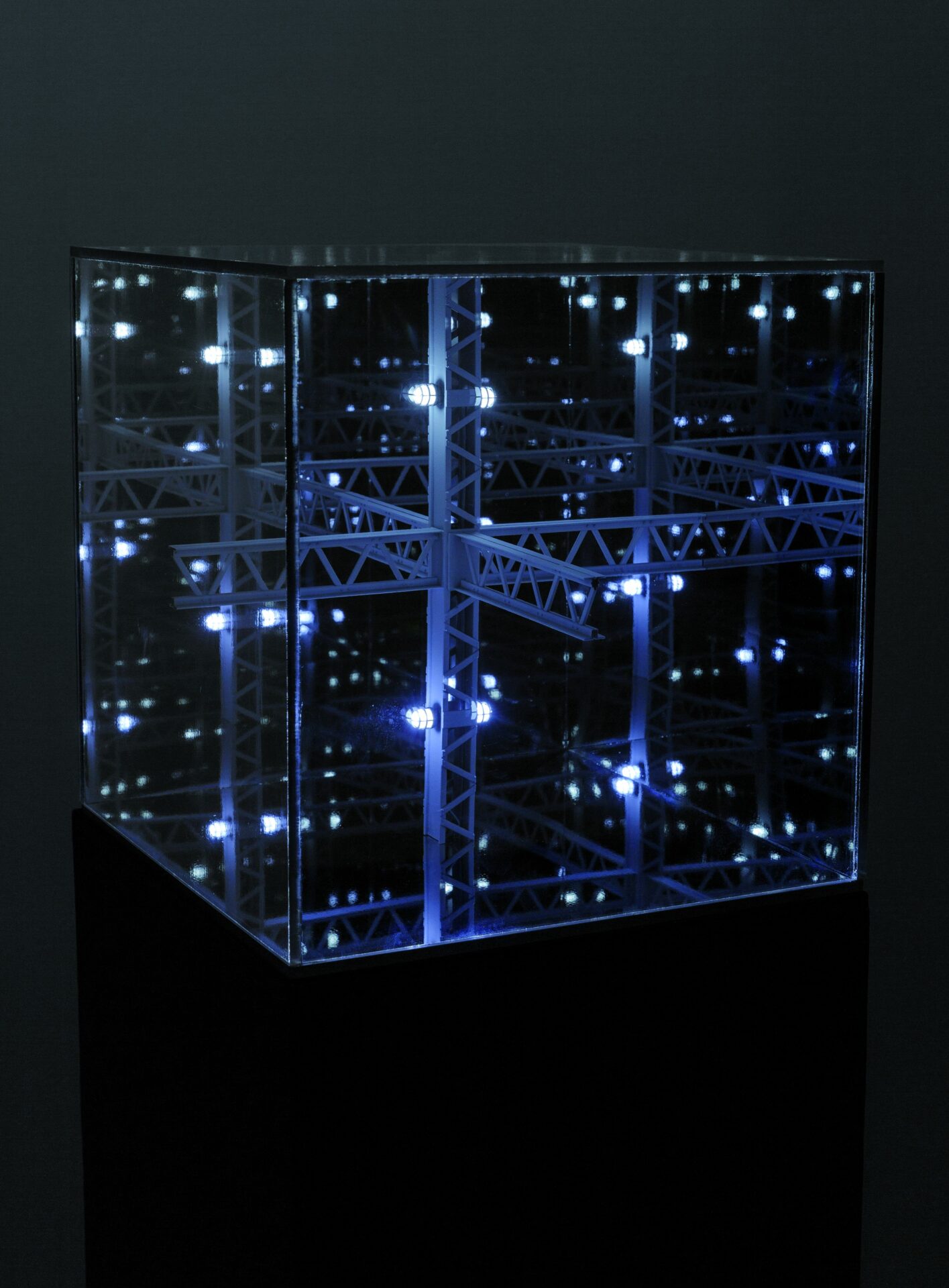

For Personal Structures, Lachapelle has chosen to present three works: Nuit étoilée (2012), The Cell (2013), and Dernier étage (2014), which he arranges in a darkened space, to some extent echoing the scenography of his recent exhibition at Art Mûr, in Montréal.2 2 - Guillaume Lachapelle, Visions, Art Mûr, Montréal, March 8 to April 26, 2014. Two of the works are presented on black pedestals, giving the impression that the models are floating in the air, and they are encased in two-way mirrors that allow us to see everything while also infinitely reflecting the elements making up the miniature universe.

The Cell, 2013.

Photo : Guy L’Heureux, courtesy of the artist

This is also the device used for Nuit étoilée. From a certain distance, the work appears to be merely an empty parking lot in which a lamppost pushes back against the darkness of the night, echoing the hackneyed cliché of a night fraught with danger. The scene, easily associated with suburban reality, would seem to convey an ironic view of urban sprawl. Yet, on taking a closer look at the glass-encased model, we are gripped with a sense of deserted space, of cosmic emptiness, as if we were inspecting part of a ghost town. By playing with the mirrors to create endless spaces, Lachapelle manages to preserve the venue’s usual appearance, with its recognizable and identifiable particularities, while also prompting the viewer to ponder the representation. Having to lean over to contemplate the model, viewers find themselves overlooking the parking space, as if flying over it. This birds-eye view is the artist’s way of inviting us to abandon ourselves to his universe, to forgo the embodiment of space for a moment, to take some distance to truly appreciate things.

The Cell, 2013.

Photo : Guy L’Heureux, courtesy of the artist

Nuit étoilée, 2014.

Photos : Guy L’Heureux, courtesy of the artist

The Cell attempts to further complicate this question of the viewer’s ideal position. While, from a distance, we see what seems to be merely a building under construction, up close, it is as if we were positioned on top of the structure. The high-angle point of view engaged in the contemplation thus induces a sense of dizziness. Due to the play of reflecting surfaces, we see only the structure stretching out nearly to infinity, whether laterally or toward the sky or the ground. This optical immersion undermines our visual bearings and, in a way, fosters an impression of disembodiment. The work is an invitation to immerse ourselves in it, to plunge and obliterate oneself in it. More than captivating our interest, it also fascinates our eye.

This mysterious fascination is also to be found in Dernier étage. Different from the other two, the presentation of this work reconnects with a mode that Lachapelle has used in some of his prior creations. First, the viewer sees a miniature emergency staircase that adjoins an architectural element of the same dimensions and which seems to sink into the wall. One has to come quite close to notice that this work, though it does not present the impossible perspectives or curved passageways that trick the gaze (as with Lachapelle’s previous productions), does contain an extraordinary dimension. Again, through a play of mirrors, office spaces are multiplied, giving the impression of an endlessly reproduced space. When we peek into the opening of this top floor, a huge space appears, like an unexpected surprise. By plunging into this opening, we apprehend the existence of another possible world, of a universe not just previously unknown but literally unimaginable from our exterior position as visitor.

Ruining the Present

This need to engage the act of seeing is also present in the work of Simon Bilodeau. Here, this concern rests on the mode of exhibiting the works through which the artist tirelessly explores the idea of a fragmentary, incomplete unveiling. He thus conveys to visitors the intuition that they must themselves induce the connections between the various elements, infer the whys and wherefores of that which lies before their eyes. Moreover, his aesthetic, which suggests disorder and gives considerable room to debris and grunge, seems an invitation to the preparation of ruins, as one might “prepare leftovers.”

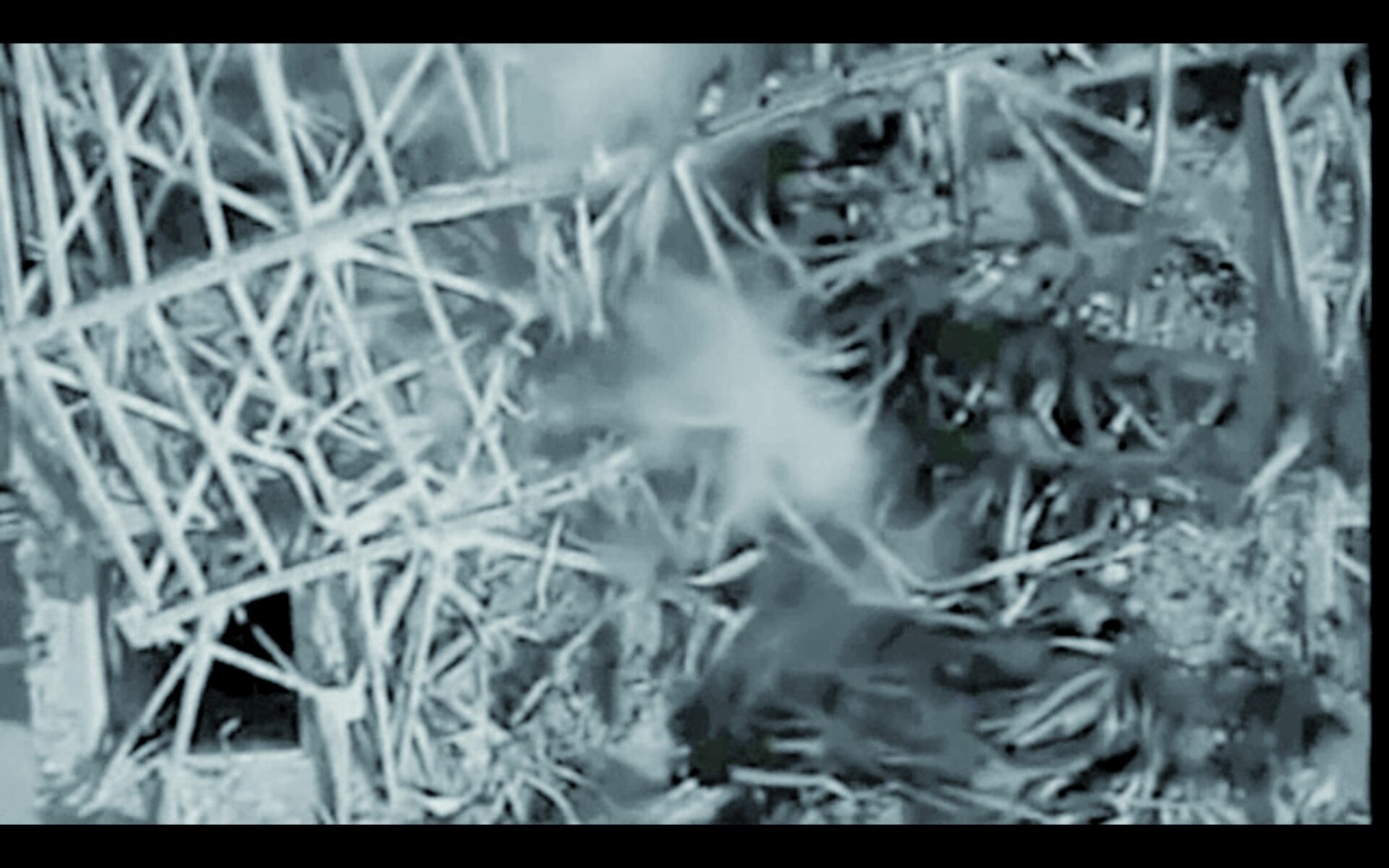

Ce qu’il reste du monde, 2013, video stills.

Photos : courtesy of the artist

It must be said that a large part of Bilodeau’s production is articulated around the idea of ruins. However, it is never a question of ruins sculpted and polished by time. Rather, viewers find themselves before remains and rubble that seem imbued with a certain violence, so strewn with splinters, fragments, and gravel are some of his settings. At other times, ashes (of the artist’s own paintings) placed under glass or in a kind of basin, recall the destructive power of fire. These presentational strategies practically oblige us to adopt an archeological vision, to seek the truly significant element out of the heap of materials, that which can invest the whole with meaning.

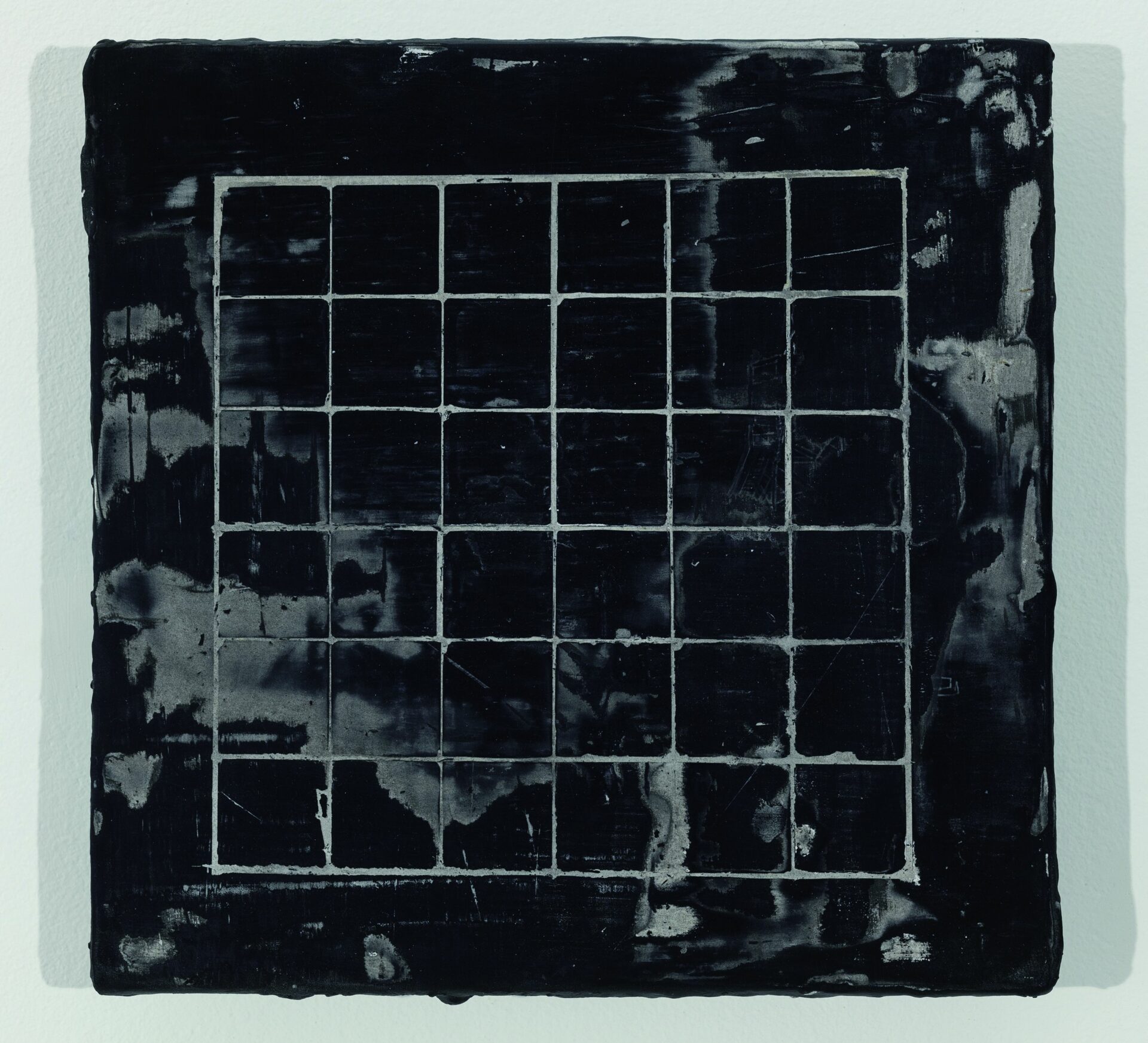

For Personal Structures, Bilodeau selected three small-scale paintings, two drawings, and a video presented as an installation. These works were previously shown in very different configurations in two of his recent exhibitions: Ce qu’il reste du monde, at the Plein sud art centre in Longueuil, from May 25 to July 6, 2013, and Ce que l’on ne voit pas qui nous touche, at Art Mûr, from November 1 to December 20, 2014.3 3 - The titles of the two exhibitions recall other well-known titles: in the first case, Ce qu’il reste de nous (2004), the film by Hugo Latulippe and François Prévost that is devoted to the Tibetan people, to whom the exiled Dalai Lama sends a message of hope by way of the film; in the second, that of the book by Georges Didi-Huberman, Ce que nous voyons, ce qui nous regarde, which deals with the question of the act of looking. I would like to think that these somewhat discreet allusions are clues, keys for reading and grasping the meaning of the body of work submitted to the visitor’s gaze. In the film, it is a question of the disappearance of a people; in the book, of a reflection on the loss associated with the fact of seeing. As it was for Lachapelle’s works, the gallery space is bathed in a subdued light. For many, the video installation likely appears to be the main piece in the artist’s proposition. However, as is often the case with Bilodeau, the function of the paintings and drawings is not to contextualize the sculptural elements, but to participate in the image constituted by the exhibition as a whole.

The drawings resemble surveys of buildings more or less in ruins. Placed under tinted glass, they emerge slowly, compelling the viewer to patiently examine the surface. This sustained gaze is also appropriate for taking in the textured universe of the artist’s paintings. His highly nuanced work, variegating shades of black, white, grey, admirably renders the idea of a kind of successive layering of material, as of sedimentary strata. The iconography of some of these pictorial works calls up visual connections with the image that we have of archeological excavation. It invariably suggests aerial shots of territory marked out by rope grids to help reconstruct the surveyed site.

Ce qu’il reste du monde # 4, # 2, # 6, 2013.

Photos : courtesy of the artist

The video work presents images of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, which had been badly damaged during the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami. The images used in the video were captured the day after the event by drones, which offered the only way to examine the structure given the high levels of radiation. The presentation is looped, lending the tragedy a sense of inevitability, of being part of an ineluctable cycle. Bilodeau dramatizes the exhibition by embedding the monitor in the wall and building a kind of derelict construction site around it. Thus, the rubble strewn on the ground suggests that the video was uncovered during demolition of one of the palazzo’s walls or during archeological excavations in the distant future. Either way, it appears as though the labourers had abandoned their work. Why? One may imagine that they had fled on discovering the video and realizing that its encasement in the wall had been a way of controlling the radiation emanating from it. The penumbral gallery’s irradiation in the light of the monitor then takes on a rather disturbing dimension, prompting visitors to reconsider their presence on the premises.

A work of art may not be “the highest and absolute mode of bringing to our mind the true interests of the spirit,” as Hegel thought,4 4 - Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Leçons d’esthétique, cited in Giorgio Agamben, L’Homme sans contenu, s.l., Circé, 1996, 72. (our translation). but it does allow the spectator to become aware of the state of the world in which he or she lives. The work with materials, so different in Lachapelle and Bilodeau, nonetheless plays a similar role — that of troubling perception, engaging it in an active reading of forms and content, inducing it to be attentive to that which it confronts. Around this concern for the gaze, neither artist is merely seeking a strategy for grabbing the visitor’s attention. On the contrary, their creations find their real effectiveness in their ability to renew the experience of vision. The time of visual contemplation that we grant them constitutes a moment in which to question our relationship with the world, how we hold and position ourselves in it. Of possible significance is the fact that Lachapelle and Bilodeau both use mirrors in their production. Whether in its untinted aspect or in the form of crystals or shards piled into pyramids, the mirror seems to indicate an opening that gives access to other possibilities, to that which is hidden behind. Beyond the invitation to cross this space, the mirror prompts us to produce our own reflections on the world around us.

Translated from the French by Ron Ross