photo : © Camille Henrot, permission de | courtesy of kamel mennour, Paris

What if our relationship with the world had never ceased to be archaic? Since the Enlightenment, Western culture has eschewed the irrational in favour of scientific explanations and technological advances. Yet, periodically, doubts surface as to the success of these advances, and with them the feeling that within each of us a core of primitiveness has remained intact. In the early twentieth century, Jung theorized on a common collective unconscious made up of age-old archetypes, while the Surrealists (Breton, Bataille, Leiris) sought forms of basic representation in non-European cultures. Today, Bruno Latour claims that we have never been modern1 1 - Bruno Latour, Nous n’avons jamais été modernes: essai d’anthropologie symétrique, Paris, La Découverte, 1991 [We Have Never Been Modern] and Sur le culte moderne des dieux faitiches, Paris, Les Empêcheurs de tourner en rond, 2009 [On the Modern Cult of the Factish Gods]. since progress is simply a disembodied fantasy, and facts can never be divorced from beliefs. The works of Camille Henrot concur with this line of thinking and reveal the primitivism of our relationship with the world, even in its most high-tech manifestations. In Henrot’s oeuvre, the desire to own objects, which we tend to associate with consumer society, is shown to be symptomatic of an irrepressible regressive impulse; distinctions between Western and indigenous societies are blurred, and linear time, a corollary of the notion of progress, is replaced by a cyclical concept of time. In short, all the certainties of Western culture are thrown into question.

One of the ways in which Camille Henrot thematizes the primitiveness of our relationship to the world is through the phenomenon of collecting, a pursuit generally considered to be relatively noble depending on the objects coveted — collecting paintings is deemed highly spiritual, whereas spoon or sticker collections are seen as rather childish. For Henrot, the act of collecting always stems from a complex and problematic desire. It responds to a need for accumulation that reflects a transference of emotion toward the objects around us and, in this regard, is never far from animist beliefs.

photos : © Camille Henrot, permission de | courtesy of kamel mennour, Paris

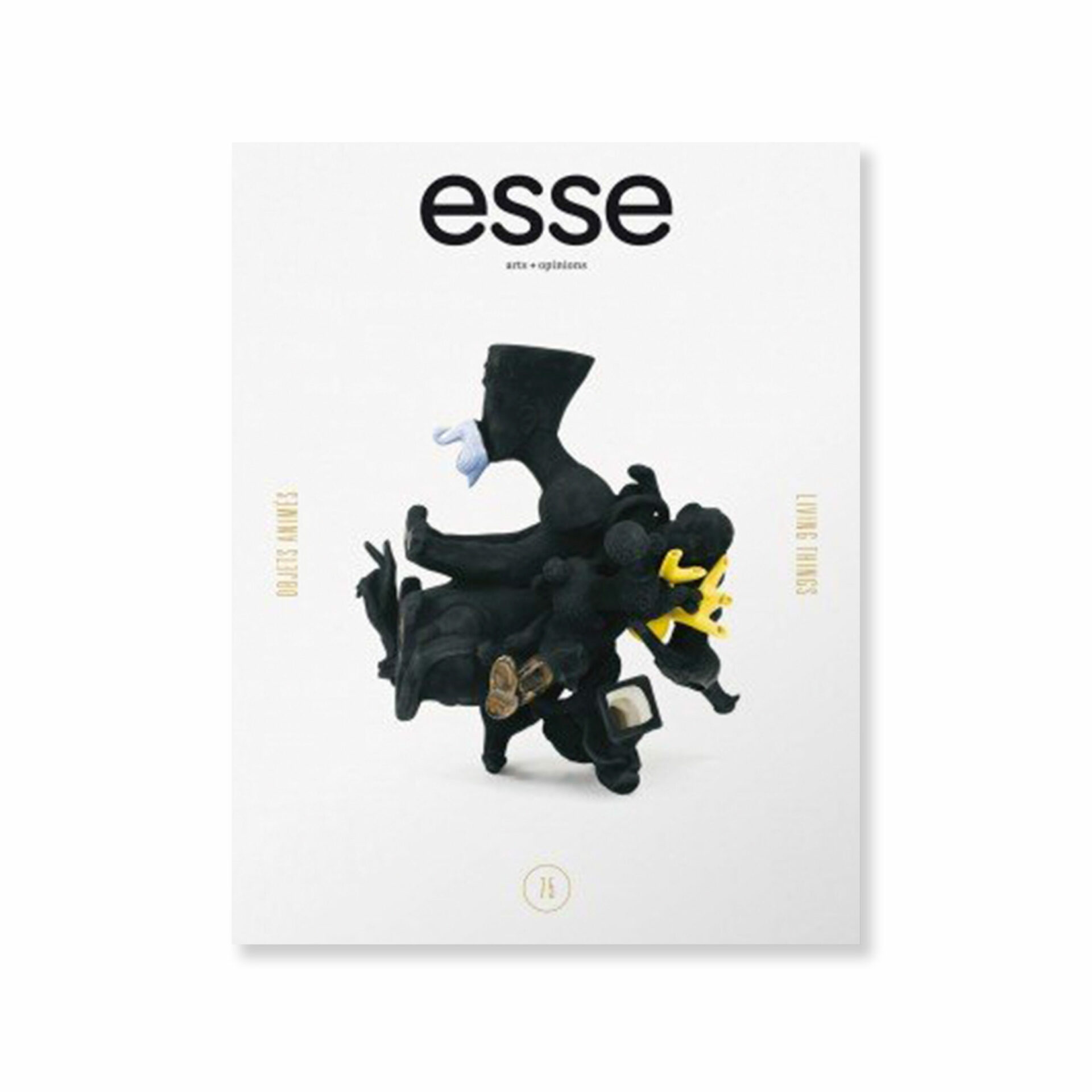

Motivated by her own desire to collect objects, in 2009 Camille Henrot completed a series of ten photographs of stalls at a Belleville flea market. The title of the series, Trésor public, echoes the market’s location opposite the revenue office of the public treasury and also suggests a revaluing of the objects on sale. The photographs show old cell phone chargers, past issues of L’Équipe magazine, last season’s shoes… Despite the meagre offerings at the market, Henrot always managed to buy something and transformed her finds into displays of proto-artistic objects — a series of 36 sculptures, titled Objets augmentés (2010), inspired by African ritual objects named boliw.

Although aesthetically pleasing, the fabric or cotton covered boliw are in fact quite unsettling for what they contain: various repugnant materials, including bones, animal blood and excrement. To reproduce this ambivalence, Henrot covered the objects she purchased at the Belleville market with earth and tar, creating a uniform surface and giving them the appearance of traditional sculptures. Just as boliw contain the secrets of African tribes, Henrot’s “augmented objects,” which at first glance appear to be precious sculptures, contain the waste of consumer society. They are the embodiment of everything we would like to keep well hidden beneath the veneer of civilization.

photo : © Camille Henrot, permission de | courtesy of kamel mennour, Paris

Henrot’s sculptures are often inspired by primitive artworks and explore the attraction the latter hold for us. It is in order to possess these objects that she reproduces them from readily available materials. The act of collecting them makes the question of possession reflexive: the object possesses us as much as we possess it. This is the case with her work Tevau (2009), in which two firehoses are assembled to form a replica of a Melanesian ritual object, traditionally made out of coils of braided red feathers (the title of the piece is a phonetic transcription of the original object’s name). In Melanesia, the tevau is sometimes offered to repair a wrong, an aspect that is retained in the replica. Through her own desire to possess the object, Henrot questions the desire of Westerners to acquire primitive artworks, a desire that carries a historical burden of guilt. In L’Afrique fantôme, Michel Leiris describes his guilt about stealing an object that appealed to him and his sense of malaise at finding himself torn between aesthetics and ethics. The piece created by Henrot echoes this type of ambivalence and proposes, not without humour, a way to end the circulation of primitive artworks: make fakes for collectors and return the original works to the people who created them. For the artist, any object can be invested with totemic power, provided one believes in what it represents.

These reflections encourage us to see that fundamentally our relationship with objects in “civilized” societies is not very different from that in “primitive” societies. Each culture creates its totems. Since the birth of social anthropology in the nineteenth century, we have become accustomed to observing primitive ritual practices at a distance, as though they were foreign to us. The installation Sanctuaire (2010) is a radical critique of this attitude. A device suited to minute observation, consisting of a camera tripod and a projector, is directed towards a suspended ear of corn — a sacred and symbolic plant throughout South America. Henrot had originally planned to display several varieties of corn from across the world to show the plant’s biological and symbolic wealth. However, strict agricultural laws prevented her from importing the plants, so she focused on the only one she could obtain — an ear of Hopi corn from New Mexico — to explore the Westerner’s gaze. Up until recently, anthropologists believed that corn revealed the “cultural integrity” of a people — a much-prized quality in their research. From the purity of a variety of corn, they deduced that the people who cultivated it had been self-sufficient and isolated, and had therefore conserved, from a Western perspective, a degree of cultural purity that made them interesting. The title of the work is an ironic critique of this interpretation, since it evokes Faulkner’s novel Sanctuary, in which a corncob is a tool of rape and a symbol of the emergence of evil.2 2 - William Faulkner, Sanctuary, novel published in 1931. Today, corn is at the heart of intense environmental debates around GMOs and biofuel. All of these meanings — from the golden burst of yellow kernels evoking the sun for Native Americans to the genetic engineering of new corn strains — are illuminated through the projector in this work.

photo : © Camille Henrot, permission de | courtesy of kamel mennour, Paris

The rationalization of our relationships with objects might lead us to believe that irrational interpretations and rituals have now completely disappeared from our societies, supplanted by technology. Yet for Henrot, technology is the object of a cult in the most archaic sense of the term. This is the meaning conveyed by a set of sculptures titled Le prix du danger (2010), consisting of airplane wings cut and perforated with decorative motifs reminiscent of primitive art and positioned like totems. The patterns draw attention to the undeniable fragility of these objects,3 3 - See Freud’s definition, in Totem and Taboo (1913), in which he cites the founder of religious anthropology, J. G. Frazer: “‘A totem,’ wrote Frazer in his first essay on the subject [Totemism, Edinburgh, 1887], ‘is a class of material objects which a savage regards with superstitious respect, believing that there exists between him and every member of the class an intimate and altogether special relation.” (Totem and Taboo: Some Points of Agreement Between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics. Trans. James Strachey. Routledge and Kegan Paul. p. 103). It is important to note, however, that Freud uses these anthropological references to resolve issues related to neuroses, which would imply that there might be a healthy state of totemism. This idea runs counter to the thesis of this essay. which at the same time (or so we tell ourselves) can withstand any degree of turbulence. Doesn’t this attitude come very close to the definition of totemism as a “superstitious respect” for a material object? Are our mixed feelings of confidence and terror vis-à-vis airplanes not the modern version of a relationship with the world that nothing can change? In a similar vein, another work by Henrot reveals a hidden archaism, this time in the guise of cars in the popular imagination. Espèces menacées (2010) is a set of sculptures made from the engine parts of car brands and models named after wild animals: Jaguar, Porsche Cayman [Caiman], Ford Mustang… By underlining this recurrent theme within the automobile industry, the artist suggests that cars are the totems at the heart of our civilization.

photo : © Camille Henrot, permission de | courtesy of kamel mennour, Paris

These reflections tend to blur the distinctions between Western and “primitive” societies. To quote the terms used by Claude Lévi-Strauss in his radio interviews with Georges Charbonnier, “hot societies,” based on change and the potential for differentiation, come closer to “cold societies,” which “tend to remain indefinitely in their original state.”4 4 - Cited in Georges Charbonnier, Entretiens avec Claude Lévi-Strauss, Paris, 10/18(1959): 38. The concept of sustainable development, for example, is a current symptom of this shift. Henrot’s sculpture titled Tableau de navigation (2011), in reality a copper radiator, evokes the possibility of such changes in temperature, depending on the degree to which societies borrow each other’s modes of functioning. It can also be interpreted as a metaphorical tool that allows each person to adjust his or her own temperature. But the artist approaches the idea with gentle irony: the object’s shape resembles that of a navigational chart from the Marshall Islands, now conserved at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The chart, long considered a shamanic object, was shown to be an extremely accurate nautical map of the Pacific in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Until then, Westerners, caught up in their own prejudices, did not believe primitive peoples capable of such scientific knowledge and firmly relegated the charts to the realm of magic. Henrot invites us to think about this presumed dichotomy, now that we recognize that in all societies, the connection between science and belief is a lot more complex than it appears.

At the heart of our own mythology, the notion of progress — the image of humanity gradually emerging from a passive, primitive state to become self-reliant and rational, following an irreversible, linear course of time — is therefore called into question. The works of Henrot, in contrast, embrace an Eastern-inspired, ahistorical notion of time. Her film Cynopolis, shot in Egypt in 2009, juxtaposes the meanderings of a pack of stray dogs on the site of the Saqqara pyramid with the visits of tourists and digs by archaeologists. The spectacle of this ill-assorted ballet leads one to question whether the activity of the dogs, despite their ignorance of the value of the ruins, is not less destructive than that of the tourists — or even the archaeologists! Instead of drawing us closer to history, our cult of the past distances us from it.

photos : © Camille Henrot, permission de | courtesy of kamel mennour, Paris

Shown in the same exhibition, at the kamel mennour gallery in 2009, the slide show Egyptomania (2009) emphasizes this distancing effect. Screenshots from eBay and photos of objects purchased by the artist on the website show the gradual erosion of an authentic interest in Egypt — from high-brow references such as a publication by the Egyptian Antiquities department of the Louvre to low-brow merchandise such as Nefertiti soap or, following an image of the Hollywood classic The Mummy, a pot of artificial maggots for Halloween… Le Songe de Poliphile, shot in India in 2011, suggests that Henrot embraces a more sinuous notion of time, filled with oscillations and entanglements, like the figure of the snake that is the subject of the work. This means that learning, discovery and improved living conditions do not follow a straight, unilateral course, but rather occur little by little, through acts of exchange. Another video, Million Dollar Point, shot the same year at a diving site off Vanuatu, suggests that those who contribute the most in the exchange are not always the ones we might assume. The video shows underwater shots of military equipment dumped by the US Army as part of Operation Magic Carpet,5 5 - A vast operation to withdraw US troops and arms throughout the world, from 1945 – 1946 an exercise to repatriate troops back to the US at the end of the Second World War. Rumour has it that the people of Vanuatu offered to purchase the equipment for a million dollars, but, fearing political independence movements, the Western powers preferred to render them useless by dumping them into the ocean.

photo : © Camille Henrot, permission de | courtesy of kamel mennour, Paris

The images of the submerged remains are shown in parallel with a highly stereotyped clip in which Polynesian women dance around a robust moustachioed man singing in French — a laughable reincarnation of Gauguin. Through its insistence on the dance of the Polynesian women, the video invites the viewer to look beyond the cross-cutting of misunderstandings, suggesting that things are intertwined in a more subtle manner. Although the Polynesian women are instrumentalized here by the desire of the dominant man, they served as a model for the liberation of Western women in the post-War period…6 6 - Interview with the author, December 2011. Similarly, in the video Coupé/Décalé (2011), we discover that a Melanesian rite of passage was the inspiration for the sport of bungee jumping, which originated in New Zealand — a sport considered high-tech by many, unaware of its traditional spiritual origins. This cultural mimicry is also reminiscent of the cargo cult. During the war, when American soldiers were stationed in the islands of the South Pacific, indigenous peoples observed that radio requests for supplies were followed by airdrops. Unaware of the logistics behind these operations, they imitated the soldiers by making calls from handcrafted radios, hoping to likewise cause foodstuffs to be dropped from the sky.7 7 - These rituals inspired the Serge Gainsbourg song “Cargo Culte,” on the Histoire de Melody Nelson album, released in March 1971. The title of this essay borrows a phrase from the song:

“And since their totem never brought down

a Boeing or even a DC-4,

they dream of hijacks and bird accidents”(Our translation) Henrot’s works show that the cargo cult is far from limited to the post-War societies of the South Pacific. All societies have their cargo cults — a combination of desire, imitation and lack of understanding.

Through objects purchased on the street or on eBay, through works imitating African sculptures and artefacts from the South Pacific, and through videos questioning cultural exchanges, Henrot leads us to examine our most basic assumptions: not only abstract values such as rationality but also, more concretely, the way we look at objects in our daily lives. For Hannah Arendt, the role of such objects was to create a stable, reassuring world (something the philosopher sensed was becoming increasingly difficult).8 8 - Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, 1958, Chapter IV, “Work.” With Henrot, in contrast, objects are unpredictable, by turns frightening and reassuring, perishable and permanent, prosaic and sacred. After seeing her works, we can never look at a firehose or an airplane wing in quite the same way again.

[Translated from the French by Vanessa Nicolai]