All Roads Lead to AIDS: Keeping the Shutters Open

The text explores the search for a history of crip art in Québec, questioning dominant archival methodologies and the erasure of Disabled and Deaf artists. It highlights the links between queer struggles, HIV/AIDS and disability, arguing for an intersectional approach.

For this residency, I wanted to experiment with a research methodology that would allow me to meet possible companions. My hypothesis was that they might guide me to an accessible opening in the history of crip art in Québec. The term “crip” originates in the negatively connoted word “cripple,” which used to refer to a disabled person. It became an insult. Then, some disabled, mad,1 1 - Like “queer,” for the 2SIALGBTQ+, and “crip,” for the disabled, the term “mad” is used with the aim of reappropriating a negatively connoted word, changing its meaning, and re-politicizing the category of “mentally ill person.” neurodivergent, sick, and Deaf communities reappropriated “crip” in a positive way to challenge the use of normalizing, “politically correct” terms. Crip is thus an umbrella term for the varied communities of disabled people and for their intersectionalities, including queer ones.2 2 - Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (New York: New York University Press, 2006).

I began this investigation with filmmaker, curator, and professor Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, as I wished to unlearn the archives and to establish a practice based on “finding precedents … at least assuming that precedents could be found.”3 3 - Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London and New York: Verso, 2019), 17.

When Azoulay tells us to find such potential pre-colonized worlds, to bring them forth, and to inhabit them here and now, I ask myself the following questions. How can this apply in the context of research into the potential history of crip art in Québec? How do I situate myself, find my crip family history, without using the dominant archival methodologies? What is the crip community outside the purview of an imperialist categorization? What did the disabled, the mad, the sick, the neurodivergent, and the Deaf do in generations before, during, and after the forced institutionalizations in Québec? Art? Nothing? Where were they? In hospice, at home, dead, in residential schools, or in other marginalized, queer, or art communities?

To the question “Where were we, the Deaf and disabled artists?” I can answer only that, in Québec, we were not in the conversations surrounding the various social movements (Quiet Revolution, struggle for human rights) or the artistic ones (Le Refus global, the emergence of artist-run centres). Indeed, at the time (and still today, in fact), the disabled and the Deaf endured forced institutionalization in Canada, which included being forced to enter institutes for the Deaf (1850–1980), residential schools for the infirm (1900–60), the Duplessis orphanages (1944–60), and, more recently, long-term-care facilities. Even after their deinstitutionalization, which began in the 1960s, most disabled individuals were left stranded and without means and wound up in other types of institutions, such as prisons, shelters, and psychiatric hospitals. Like other marginalized people, we were out of the loop when artists began creating possibilities for self-determination. Of course, art-therapy workshops and arts-and-crafts training were offered. However, as pointed out by Suzanne Commend, researcher at the Institute of Feminist and Gender Studies at the University of Ottawa and specialist in the history of physical disability in Québec, the purpose of such activity was to produce useful citizens rather than artists.4 4 - Susanne Commend, “‘Au secours des petits infirmes’: les enfants handicapés physiques au Québec entre charité et exclusion, 1920-1990,” PhD dissertation, Arts and Science Department, Université de Montréal, 2018, 184.

Unfortunately, too little importance was given to the work of these craftspeople, compared to that of the signatories of Le Refus global, born in the same period, and so there is no documentation on either their art production or their identity. Faced with this, I had to consult Azoulay. I imagined her telling me, “Instead of bemoaning the inaccessibility of this lost knowledge, engage in a project that attains this knowledge differently, with other affected people.” So I turned to the history of the AIDS crisis.

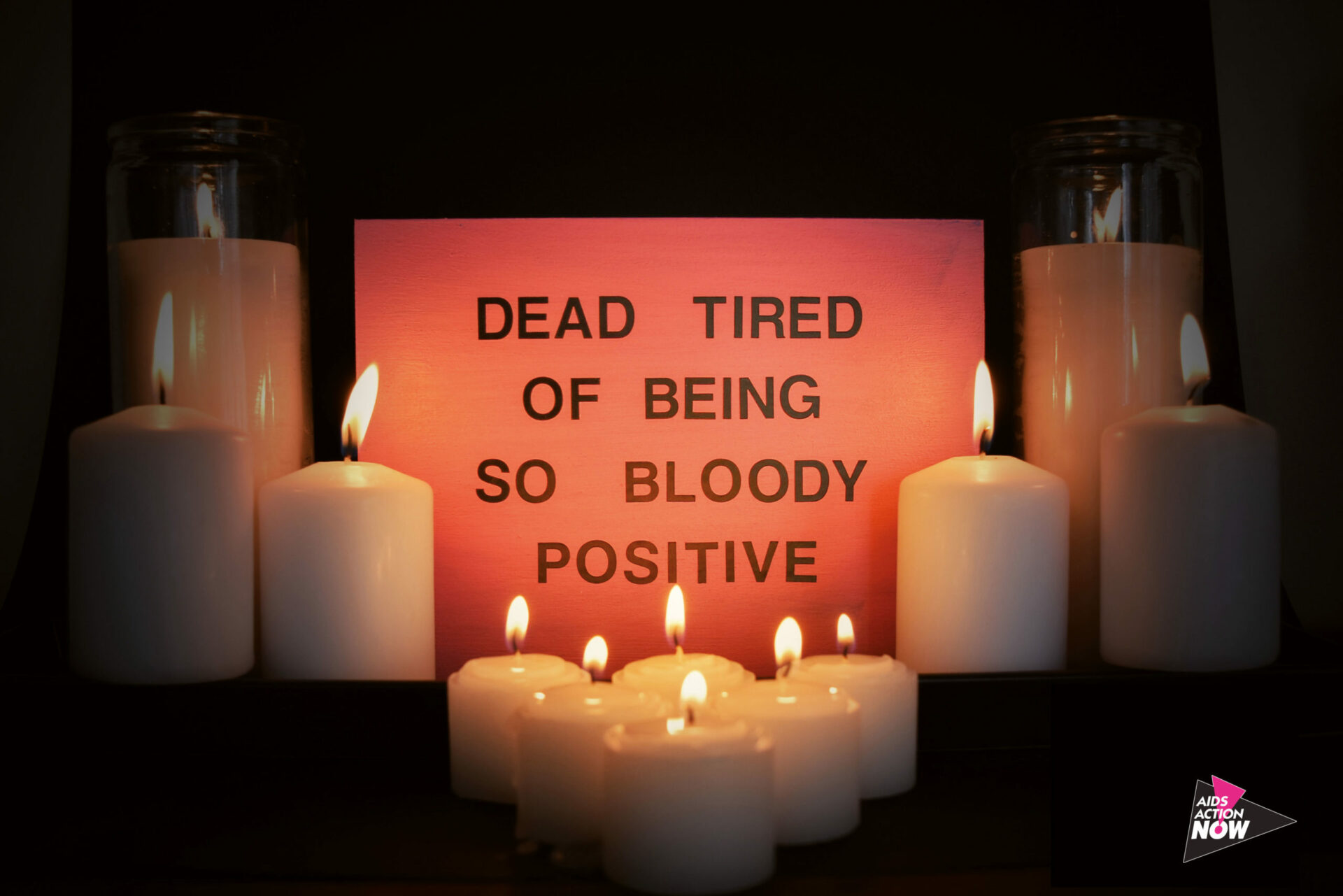

In an article published in Esse magazine in 2017, “PosterVirus: Views from the Street,” Adam Barbu discusses the PosterVirus project and its posters on the topic of HIV/AIDS, which were mounted in public spaces throughout Canada.

He reminds us that “our society is anything but post-AIDS.”5 5 - Adam Barbu, “PosterVirus: Views from the Street,” Esse, no. 91 (Fall 2017): 32 As he points out, we have collectively convinced ourselves that AIDS is a thing of the past, partly because of a few medical advances since the 1990s, research that we only rarely question. Barbu goes further still by observing the tendency, in periods of crisis, to want to return to normality—that is, to the situation before the sickness—and to believe in it. It inevitably recalls the COVID-19 pandemic, which arose shortly after the publication of his article and during which the same phenomenon occurred. The “fantasy” of returning to the time before COVID, of erasing all the harm done, which persists, particularly among those living with long COVID—and with grief—isn’t very different from what Barbu lays out regarding HIV-positive individuals.

Alex Noël, in his article titled “Les boîtes noires,” published in the magazine Liberté,6 6 - Alex Noël, “Les boîtes noires,” Liberté, no. 341 (Winter 2024), accessible online. is specifically concerned with the silence surrounding AIDS in Montreal, including with respect to the artists who succumbed to the disease before receiving any recognition from the cultural milieu. Noël sadly observes the blotting out of that pandemic, as much by governments as by universities, from both the historical and artistic perspectives. Like Deaf and disabled artists, artists living with HIV have very few elements to lean on in view of a potential crip history—a necessity for initiating an eventual reconciliation with art history, but especially to gain self-recognition and attain the privilege (which shouldn’t be one) of finally cherishing and celebrating oneself.

In his presentation of the “AIDS Generations” theme for Spirale magazine,7 7 - Daoud Najm, “Présentation: générations sida,” Spirale, no. 248 (Spring 2014), accessible online. Daoud Najm delineates AIDS not simply as a crisis of the past but as a subject no longer “in vogue,” including in the art scene. Yet it was at the heart of the cultural scene that activism against the disease took shape, a movement that changed a broad range of practices: in design (particularly with the creation by Gran Fury8 8 - An artist collective born of ACT-UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), an activist organization fighting against the AIDS pandemic in the 1980s. and General Idea of posters and garments that fused art with activism and education, and the design of a logo representing a particular struggle, the pink triangle, which became a topic of study in marketing for its singularity and effectiveness); in film (creating its own cinematic trend to offset the prevailing (non-)representations in the media); in literature (with the emergence of a return to the body as a literary subject); and in visual and media arts (the practice of self-representation as testimony or documentary on the disease, medical environment, and grief). In this issue, Najm strives to counteract the current lack of interest, for not only is the generation having undergone the crisis still alive, with new infections continuing to occur (in 2023, the World Health Organization counted over 1.3 million seroconversions),9 9 - “HIV and AIDS,” World Health Organization, updated July 22, 2024, accessible online. but, as Barbu reminds us, “we are still without a cure, and moreover … our society continues to partake in forms of violence against those living with HIV.”10 10 - Barbu, “PosterVirus,” 32.

The dominant archival methodologies comprise a practice of separation, compartmentalization, isolation, and extraction.11 11 - Azoulay, Potential History, 229. Indeed, both in the collective imagination and in how it is treated in creative and research settings, HIV/AIDS is often broached as a category in itself, either isolated or at most linked to the “queer” category but not or very tenuously to the category of “disability.”

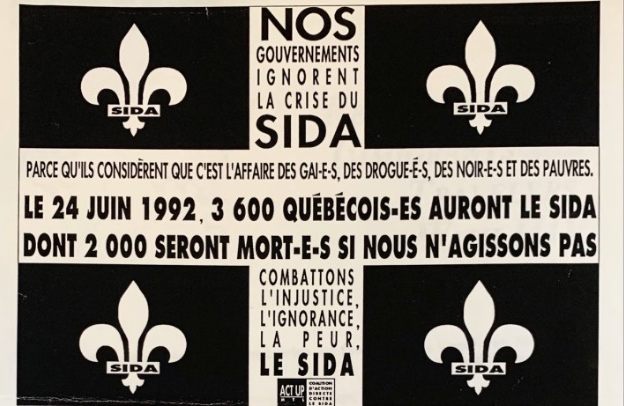

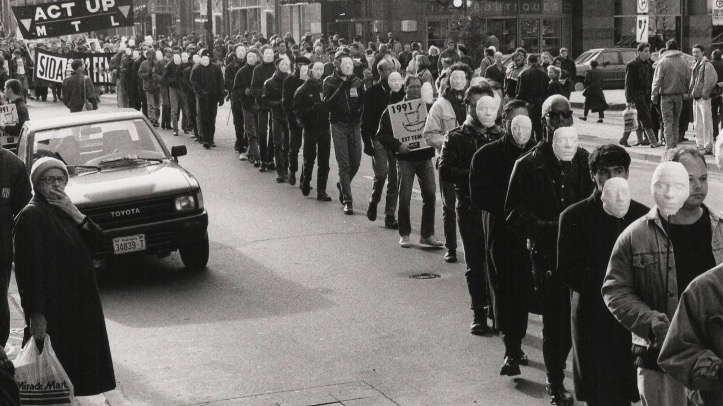

Yet, not only are the struggles of the disabled, Deaf, mad, and neurodivergent akin to those of the sick but activists during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s were artists living with HIV. They had an undeniable impact on our abled and alternatively abled lives. For instance, during the Fifth International Conference on AIDS, held in Montréal in 1989, open exclusively to politicians and scientists, activists living with HIV and their allies (ACT UP New York, AIDS ACTION NOW!, and Réaction Sida) managed to infiltrate the opening of the conference and to proclaim the 1989 Montréal Manifesto. Among other things, this manifesto demanded the establishment of laws protecting the rights of HIV-positive individuals; recognition of inequalities in access to treatment, particularly outside the West and for women; and the “conversion of military spending worldwide to medical health and basic social services.”12 12 - AIDS ACTION NOW! and ACT UP New York, Le Manifeste de Montréal: Declaration of the Universal Rights and Needs of People Living with HIV Disease, 1989, accessible online.

The health and research fields at the international level were completely transformed, as activists had successfully conveyed the importance of considering and involving the first people concerned by HIV—those who were suffering from it. This invariably recalls the slogan “Nothing about us without us”13 13 - This slogan marked the history of the struggle for justice surrounding disability in the West. used by disability rights activists around the world for decades.

In Potential History, Azoulay proposes instead to reflect on communities’ resistance and to approach archives not as “a window to the past”14 14 - “Ariella Aïsha Azoulay: Unlearning Imperial Violence,” Conversation with Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, posted December 18, 2023, by Crosstalks, YouTube, 88 min 56 sec, accessible online. but as access to these communities’ refusal to be relegated to what has been, to what is no more. By going over the archives of Montréal activists involved in the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, I practised this unlearning of the new and of the archives. I was particularly struck by the frankly intersectional posture that the images demonstrated. Obviously, the term “intersectional,” as currently understood, was not then used to refer to these activists’ stances and attitudes. The intersectional posture was manifest in the doing.

Our art history may have begun before the AIDS crisis, but that crisis was nonetheless a major element in it—a history we should (re)discover, know, and celebrate. It was already there and it continues to exist. This history “didn’t wait for critical theory to come along to understand the contours of [its] dispossessions and the urgency of resisting them.”15 15 - Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History, 17. There were precedents for current crip methodologies and for the analytical tools increasingly discussed in our institutions, such as intersectionality and multidimensionality, theorized by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw (1991) and Darren Lenard Hutchinson (2001), respectively. Yet institutions approach the issues of equity, diversity, and inclusion as if it were all new.

Photo: Quebec Guay Archives, 2022

Photo: René LeBoeuf, Quebec Guay Archives, 2022

Photo: René LeBoeuf, Quebec Guay Archives, 2022

As we can observe through the archival images presented here, a practical implementation of “inclusion and diversity” already seemed to exist within the activist movements against AIDS in the 1980s. We even notice the use of gender-neutral language on the posters, an inclusive form of writing that is still subject to debate today and that the French Academy refuses to recognize as legitimate.

For Barbu, the PosterVirus posters are an investment in what had once been, in particular in the creations of Gran Fury, a displacement of dominant curatorial methodologies and queer studies “that have the power to shape attitudes, behaviour, and responses.”16 16 - Barbu, “PosterVirus,” 32. For Noël, the alternative archives allowed him to gain access to forgotten colleagues in the small black boxes of the Quebec Gay Archives: Guy Fréchette, Luc Caron, and Kapesh Oza. A kind of “legacy, a magnificent burden, that we now transmit from one queer generation to the next.”17 17 - Noël, “Les boîtes noires,” 39 (our translation).Noël, “Les boîtes noires,” 39 (our translation). For Najm, it is from “all that could have been”—the dreams, promises, and projects of artists who have succumbed to AIDS, icons all, from Queen’s Freddie Mercury to artist friends completely unknown to the general public—that it would be possible to retrieve more than deaths from this “outmoded” era. It is a ceaselessly present conditional.18 18 - Daoud Najm, “Veilleuses: Nan Goldin de Martine Delvaux, Héliotrope, ‘Série ‘K’,’ 116 p./Diamanda Galás de Catherine Mavrikakis, Héliotrope, ‘Série ‘K’,’ 112 p.,” Spirale, no. 248 (Spring 2014), 53–55.

These authors offer avenues for using the archives to unlearn the new and to reactualize the possibilities of our histories, of our futures. For me, what matters is having found the breach that I fervently hoped for—access to a potential history of disabled art in Québec. It is that drive and profound desire to inhabit the archives of ACT UP Montréal, to join in the effort to hold back the dropping of the guillotine, and to invest in an intersectional and multidimensional solidarity, far from the archival methodologies that tear us apart. It’s a matter not of wondering how we might build a tomorrow but of how we built it yesterday,19 19 - Adapted from Azoulay, Potential History, 20: “Unlearning imperialism is asking not how it could be opposed tomorrow but rather how was it opposed yesterday.” such that the multitude of our fragments may come together and eschew the temporality of progress, in which crip artists are neither thought nor desired.

Translated from the French by Ron Ross

Map is an artist-researcher and founder of DC-Art Indisciplinaire, an artist-run center dedicated to deaf and disabled art. They holds a master’s degree with honors in research-creation (UdeM). They complete training in Québecois-French Sign Language interpretation, with a view to rethinking the functions of the art world. Their work has been presented in Tiohtiàke, Wôbanakiak, Nitassinan, Tkaronto and Szczecin. Performative in nature, their practice of creating situations transforms the state of (im)material environments through an arrangement of particular moves, where their movements are their materials as they engages them in the strangeness of their own neuroqueer processes.

Links to the articles cited: Suzanne Commend Adam Barbu Alex Noël Daoud Najm