A Taste for Critique: A Poetics of Attention

Kessie Theliar-Charles is an artist-researcher concerned with the preservation and dissemination of the heritage of Afro-descendant visual artists. As part of this residency in partnership with Art Volt, she proposes a reflection on the social role of art criticism and the importance of the archival dimension of writing.

I am not an art critic, but I can discern its forms, functions, and possibilities. I sense a writing style that can reveal itself as poetic, fluid, contradictory, sometimes simple or complex, with words unfolding in a variety of tones and rhythms. The writing can be inquisitive and considerate, but also dreaded if perceived solely as an act of judgment and assessment. We don’t grant it nearly enough of its underlying relationality.

In Montréal, where the past of artists from Haitian, Caribbean, and Black communities remains fragmented and under-documented, thinking and writing about art always takes me in their direction. My interest in the recovery, conservation, and dissemination of narratives from the margins has led me to consider art criticism in other ways. For whom do we write and to what end? My writing is conditioned by this question and leads me to examine the rarity of critical Black voices who write about art, as well as the limited production of critical texts dedicated to the art practices of Black artists.

Reflecting on and Considering Art Criticism from the Margins

I won’t linger on the structures that have caused this scarcity or on the crisis that seems to cut across art criticism in general. Nevertheless, it seems necessary to put them into the local context. We can concretely observe a lack of representation of Black artists in local galleries and art institutions up to 2018. Though late in coming, this was the year when the major exhibition Here We Are Here: Black Canadian Contemporary Art was presented at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, reshuffling the deck and allowing a fragile visibility.1 1 - Eddy Firmin, “Regard sur l’écosystème montréalais et québécois 2012-2022,” talk given at While Black, Maison de la culture Janine-Sutto, Montréal, September 2, 2022. In 2020, art institutions reacted to the social repercussions of the murder of African American George Floyd by making often insincere declarations of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement.2 2 - Paul Gessell, “The Floyd Effect,” Galleries West, June 29, 2020, accessible online. In Canada, this reappraisal produced an explosion of institutional reactions accompanied by a hasty promise to heighten the profile of Black artists in exhibitions and collections. Yet what is visibility if it doesn’t leave any traces? The production of critical writings clearly doesn’t appear to be something that this new recognition was intended to achieve. This observation is not new and is in keeping with the lacunas in the most recent documentation of Afro-Canadian art histories. Before the issue of visibility was even raised, many artists and cultural producers were concerned about the fact that their works would not receive any criticism.3 3 - Joana Joachim, “Curating, Criticism and Care, or, ‘Showing Up’ as Praxis,” C Magazine, March 15, 2020, accessible online. The issues remain the same, but here I am more interested in the spaces of possibilities that art criticism allows us to invest through its many functions. Expressing apprehensions about an art history that already marginalizes, writer and cultural critic Kelsey Adams responds that we should not confuse criticism with praise but ground it in an ethos of care.4 4 - Kelsey Adams, “A Black Curator Is Never Just a Curator,” Contemporary And, January 29, 2020, accessible online. Investing our time in experiencing each other’s cultural productions and taking interest even in those that fail is part of this considerate approach. Thinking about the margins from the margins also permits us to critically reflect on and write about Black art without limiting ourselves to questions of identity. Interpreting a work’s political aspect should overshadow neither the forms, colours, and lines constituting its aesthetics nor the uniqueness of its creator.

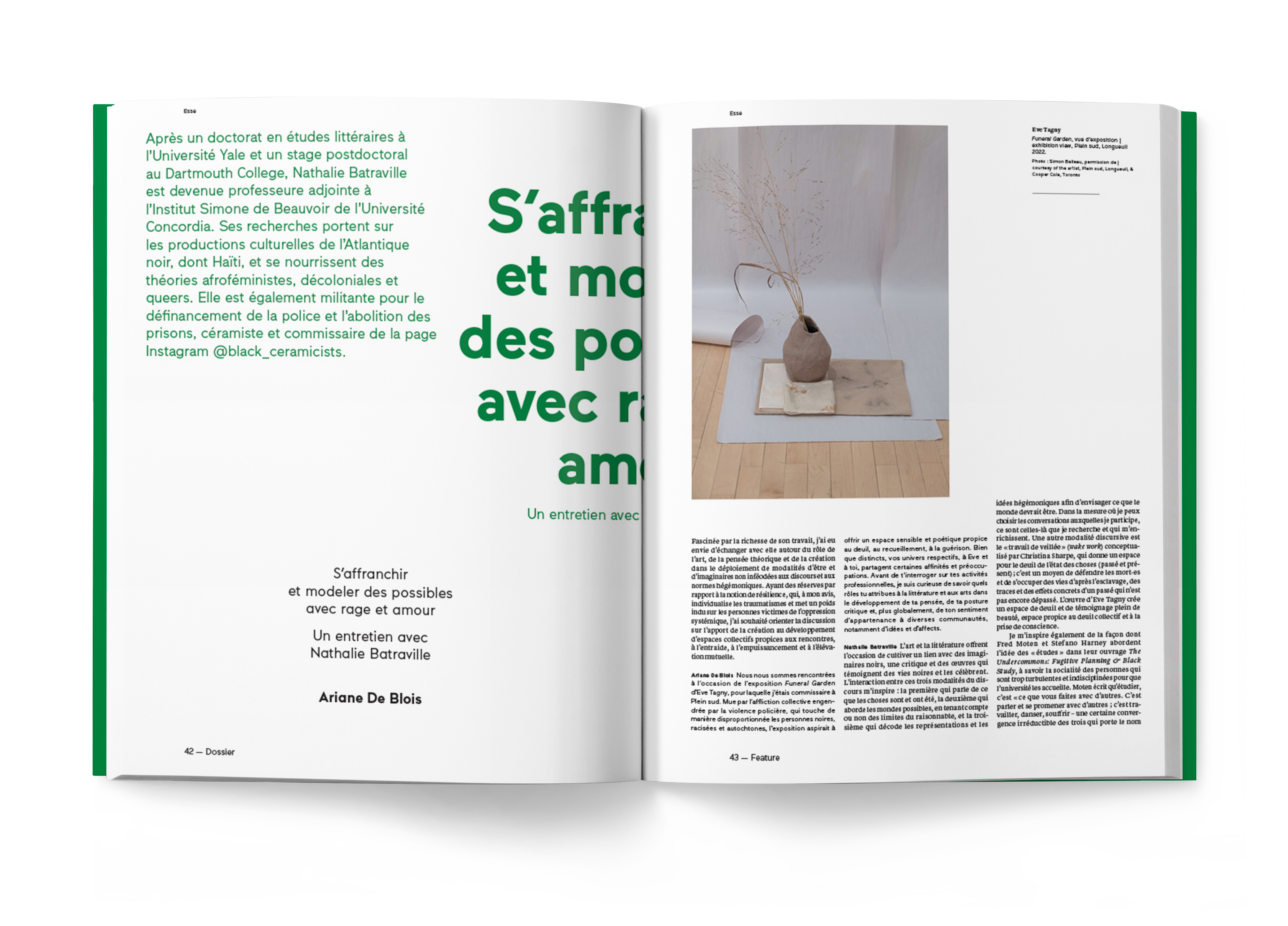

Y [Danger], detail of the installation, 2016.

Photo: Guy L’Heureux, courtesy of the artist

These considerations pave the way for a reassessment of traditional frameworks of interpretation. Eddy Firmin, an artist-researcher and coordinator of the decolonial magazine Minorit’Art, asks us to reflect on the insidious effects of coloniality on knowledge and the way in which it influences our relationship with art and culture. In the article “Cultural Imperative, Appropriationist Regime and Visual Art,” Firmin describes a personal struggle to decolonize his imaginary, free himself of Western academic models, and revitalize his gaze “made obese by the overconsumption of formal vocabularies of all kinds.”5 5 - Eddy Firmin, “Cultural Imperative, Appropriationist Regime and Visual Art,” Esse 97 (Fall 2019): 73. He exposes the dilemma of cultural reappropriation, a process made difficult by an education that was not conceived for us or by us and that sows division between self and heritage. Writing critically requires knowing, knowing oneself, and knowing the other. Art criticism all too often relies on art history for its analytical tools, contextual knowledge, and reference structures. We therefore need to make extra effort to find and disseminate what we have been taught to forget. If we engage in anticolonial thinking, our starting point must be that of a disobedient relationality that constantly challenges and refuses to submit to normative academic reasoning.6 6 - Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 45. Disobeying in order to better develop oneself is what professor Katherine McKittrick proposes in her creative critical approach within Black methodologies. Nou se nèg ak nègès mawon. We transgress, we escape.7 7 - For Martinican poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant, marronnage is a form of cultural resistance and a vital Caribbean tradition in the face of the established order. (Marronnage refers to the process by which enslaved people escaped plantations and extricated themselves from slavery; therefore, it indicates a continual process of freedom. –Trans.) This is important to remember, particularly in places of obedience such as universities. Having the legitimacy to be critical is not limited to having a successful university education: this legitimacy can stem from self-taught practices and thinking grounded in other spaces of knowledge and creation.

Art Relation Instead of Art Criticism

The question of accessibility to our history necessarily influences accessibility to art criticism. This fall, I met poet, art critic, and independent exhibition storyteller Chris Cyrille and multidisciplinary artist Kenny Cairo in a series of workshops on Caribbean critical thinking organized by the Contemporary And platform. These gatherings reoriented me toward art criticism from a Caribbean perspective. Chris led the workshops and redefined art criticism as an act of watching over art, a gesture of care, in which the main activity is listening even before writing. For him, a person who engages in this type of writing watches over and accompanies the cultural object on which the writing depends. Art criticism as art relation is a specific type of writing, a way of being with the other. Kenny doesn’t consider himself an art critic. His practice consists in collecting visual and audio documents in various fields of research, documents that he then transforms with digital tools. His use of archives to critique contemporary activities piques my curiosity. He suggests that art criticism can be an artwork in itself. For both Chris and Kenny, art criticism is not limited to writing. The subject of orality brings me to an emblematic Montréal reality, that of language choice. For Chris, writing becomes relational: “Moving between one language and another means moving between one concept and another.” In Montréal, a conversation can easily include French, English, Haitian Creole, and fragments of Spanish and Arabic, sometimes without the speaker even being aware of it. The worlds complement each other, the cultural materials combine and, above all, understand each other. Inevitably, this pluralistic reality influences our way of thinking about writing. If an artwork narrates something, what language should transmit it? Chris advocates that we need to invent a writing that both expresses our multiplicity and has the ability to bring us together.

We can find these poetics of care and relation in independent curator, writer, and art critic Eunice Bélidor’s review titled “Dans l’atelier de Thea Yabut.” There is a gentleness in her text. It begins with an encounter, an open window onto the intimacy of friendship. It’s art criticism as art relation. There is a willingness to understand the artist’s practice and not just interpret it. The primary object here is not the work as finished product but the artist—her ideas, intentions, and ecosystem. In her description of Yabut’s workspace, Bélidor indicates that “without specific plans, the studio is a place of questioning, of freedom; nothing interferes with this process.”8 8 - eunice bélidor, “Dans l’atelier de Thea Yabut,” Esse 103 (Fall 2021): 97, accessible online (our translation). Similarly, art writing could be thought of as a studio, a fluid space in which the writer explores, observes, and lets themself be transformed by what they discover.

Critique that Engages in Dialogue

Writing about our cultural manifestations allows us to contribute to raising awareness and constructing the autonomy of our history. We are witnesses; therefore, we can legitimately interpret and respond to them. Dialogic spaces at the intersection of art, culture, and community play a crucial role in this. Consider the Montréal iteration of the Canadian While Black initiative, organized by curators Dominique Fontaine and Cécilia Bracmort in fall 2022. This series of forums and participatory presentations aimed to explore the limits and possibilities of the relationship between contemporary art spaces in Montréal and Black artists, arts workers, and audiences. The need for these types of gatherings stems from the reality of Black artists and critics who must continually confront an art world so embedded in a policy of exclusion that their relationship with art and aesthetics becomes overwhelmed by the effort to challenge and change the existing structure.

Being critical therefore implies an exchange in which sharing ideas, without a clearly defined beginning or end, opens up a space where different futures can be imagined.9 9 - McKittrick, Dear Science, 25. Dialogue becomes the infrastructure that generates the production of knowledge.10 10 - Lindsay J. Twa, “Developing Diasporic Dialogues: James A. Porter, Loïs Mailou Jones Pierre-Noël and the Writing of Haitian Art History,” Gradhiva 21 (2015): 48–75. Writing critically about each other becomes a concrete act of reclamation that enables us to cultivate our uniqueness and tell our stories. In an interview with curator Ariane De Blois titled “Becoming Free and Modeling the Possible with Rage and Humour,” Afro-feminist researcher, artist, and educator Nathalie Batraville suggests envisioning art and literature as spaces that allow us to cultivate deep connections with Black imaginaries and to develop criticism and artworks that attest to the complexity of Black lives and celebrate them: “I like to think of art and text within this capacious understanding of creativity and invention.”11 11 - Ariane De Blois, “Becoming Free and Modeling the Possible with Rage and Humour: An Interview with Nathalie Batraville,” Esse 108 (Spring–Summer 2023): 49. By situating intersections between art and politics and between the intimate and the collective, Batraville shares a way of thinking that relies on these connections to build spaces in which Black narratives and voices move freely and strongly. The dialogue between creation and social experience also relates to the concept of art criticism as a poetics of attention and relation.

Art Criticism as Archival Tool

In terms of conservation and in addition to dissemination, criticism frees artworks from being frozen in time. The writing has archival possibilities in itself, endowing criticism with a dual capacity: to archive the present and to make the past contemporary. Here, it is not simply a question of texts becoming archives over time but also of using archives to write critiques. Might we be able to extend or expand cultural production by writing about a past exhibition that we didn’t see? Just like the archive, art criticism has the ability to take us to places where we didn’t anticipate going and to make us understand what has escaped our thinking.12 12 - Arlette Farge, The Allure of the Archives, trans. Thomas Scott-Railton (Princeton, NJ: Yale University Press, 2015), 65. The title of this article refers to this book. Art criticism doesn’t simply interpret: it produces and disseminates a space in which art, as well as the experience and impressions of artworks, can endure and become an archive of cultural narrative in itself.

In a panel discussion on the publication of Le désordre des choses: l’art et l’épreuve du politique, writer, painter, and researcher Stéphane Martelly raises the sense of responsibility contained in freedom: “It means creating spaces that are truly emancipatory for all subjects.”13 13 - Stéphane Martelly, “Le désordre des choses. L’art et l’épreuve du politique,” moderated by Sylvette Babin, virtual panel discussion, November 12, 2020, posted January 19, 2021, by Les éditions Esse, YouTube, 1:01:48, accessible online (our translation). This responsibility, which relates to creation, can also extend to the way in which art is shared. By considering art writing an archival tool, we are also asked to reflect on the modes of transmitting and sharing artworks. For art criticism to contribute to emancipatory spaces, it needs to be perceived creatively as a lever of change by the audiences and artists of our communities, so as to encourage the participation of new thinkers in this practice.14 14 - bell hooks, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics (New York: The New Press, 1995), 107. It is by working collectively and contributing to a cultural context in which art criticism and dialogue coexist that Afro-Canadian art will get its footing and carry on into the future. I am not an art critic but I care.

Translated from the French by Oana Avasilichioaei

Kessie Theliar-Charles is a transdisciplinary artist-researcher affiliated with CIDIHCA (Centre international de documentation et d’information haïtienne, caribéenne et afro-canadienne) and co-founder of the Black Art Histories Montreal research collective. Her approach takes shape through research-creation and collaborative research, fusing oral history and archival research to facilitate the intergenerational transmission of knowledge. With a particular interest in the Haitian diaspora, she focuses on the recovery, preservation and dissemination of the heritage of Afro-descendant visual artists who have been and continue to be active in Tiohtiá:ke/Mooniyang/Montréal.

Links to the articles cited: Eddy Firmin eunice bélidor Ariane De Blois