Photo: courtesy of PosterVirus

PosterVirus: Views from the Street

In turn, the signifier “AIDS” evolved as a force of stigmatization and political violence, which, as Susan Sontag argues, brought on a crisis of representation and “the struggle for rhetorical ownership of the illness.”2 2 - Susan Sontag, “AIDS and Its Metaphors,” in Illness as Metaphor: AIDS and Its Metaphors (New York: Picador, 1990), 181. According to Sontag, in order to radically alter our society’s relationship with HIV/AIDS, these knowledge structures had to be “exposed, criticized, belaboured, used up.”3 3 - Ibid., 182

It was from this perspective that artists and cultural producers began to mount direct political responses to the crisis. In particular, grassroots curatorial initiatives such as Gran Fury, the artist collective operating under ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), focused their efforts on public works that blurred the line between art and activism. Perhaps most widely known for its now-iconic poster designs SILENCE = DEATH (1987) and The Government Has Blood on Its Hands (1988), Gran Fury combatted the widespread rhetoric of fear and anxiety by producing works depicting scenes of solidarity, strength, and collective action. Its works were initially shared by means of illegal wheat-pasting and mass dissemination, and later on by strategic interventions in public advertising spaces. Notably, these public interventions contrasted with other artists’ responses to the crisis that focused on symbols of remembrance and retrieval — for example, Nicholas Nixon’s harrowing black-and-white documentary photographic series People With AIDS (1986) and the AIDS Memorial Quilt (1987), a public installation archive project composed of more than 48,000 panels dedicated to those who have died of AIDS-related illnesses. As Gran Fury writes, the popularity and cultural currency of this mode of representation, however comforting and cathartic it may be, “denotes a complicity between individual citizens, AIDS organizations and our government, where the responsibility for AIDS is consistently transferred elsewhere.”4 4 - Gran Fury, “Good Luck… Miss You,” ACT UP, 1995, < http://bit.ly/2thUvRa>. Overall, the collective rejected this type of melancholic imagery in favour of agitprop responses that explicitly targeted complicit civilians and public officials as the sources of stigma and political violence.

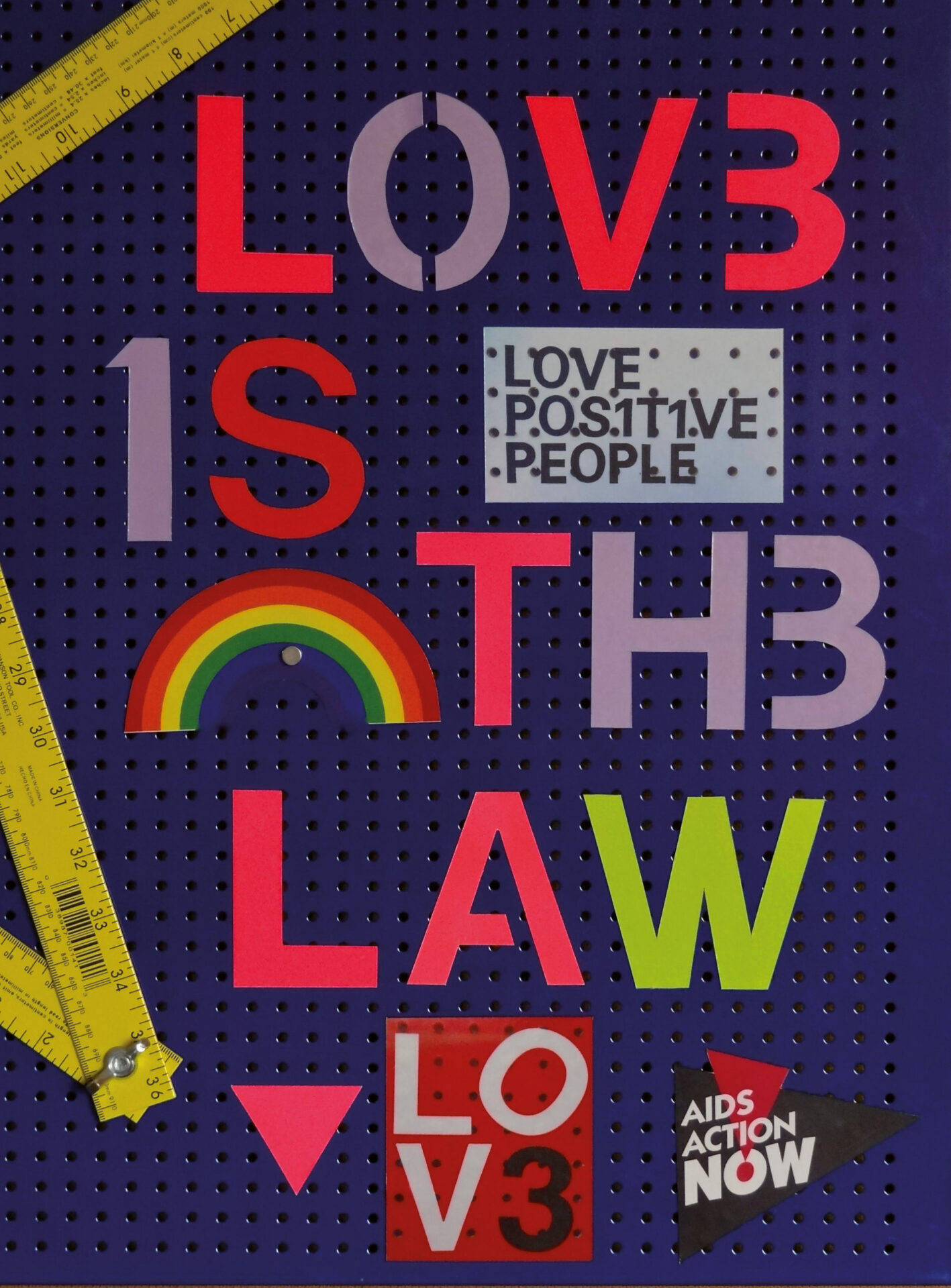

LOVE IS THE LAW, 2016.

Photo : courtesy of PosterVirus

Over the past thirty years, several curators have adopted this agitprop sensibility while addressing an evolving set of social, cultural, and political concerns. Operating in the spirit of queer curatorial projects like Gran Fury’s, PosterVirus is an interventionist curatorial initiative that operates as an affinity group of AIDS ACTION NOW!, one of Toronto’s original HIV/AIDS advocacy organizations. Each year on the occasion of the international AIDS remembrance event A Day With (Out) Art, curators Alexander McClelland and Jessica Whitbread invite various artists to create original poster works that are eventually wheat-pasted throughout the streets of various Canadian cities. Since its inception in 2011, PosterVirus has printed over ten thousand posters and collaborated with thirty-four artist participants, including Mikiki, John Greyson, Allyson Mitchell, Micah Lexier, and FASTWÜRMS. Together, the curators and artists create public installations that are both unapologetic political demonstrations and deeply personal expressions of identity and cultural memory.

She had my mom’s complexion! She was the most mild mannered in our family, shy and quiet. It would take a lot to rattle her quiet disposition and in fact, I don’t think i ever heard her complain or whine! I mostly have memories of her as my little sister, who I would be protective of all the time! And for her part, once she loved she did so unreservedly!, 2016.

Photo : courtesy of PosterVirus

PosterVirus targets the troubling fact that, in light of the medical advances achieved since the early years of the AIDS crisis, many people assume that we are living in a post-AIDS historical moment. At the same time, PosterVirus combats the fantasy that we can ever erase the damage that has been done and return to a time before AIDS. This sentiment that is aptly expressed in Vincent Chevalier’s 2013 contribution, which includes text that reads “Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me.” In an attempt to address these intersecting issues, the artist-participants challenge cultural attitudes and public health discourses that continue to marginalize, dehumanize, and erase people living with HIV. The artists also look beyond the question of social stigma by highlighting the material realities of current political issues such as the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure, the lack of widespread access to affordable treatment, and the disproportionate impact of the virus on minorities and marginalized communities.

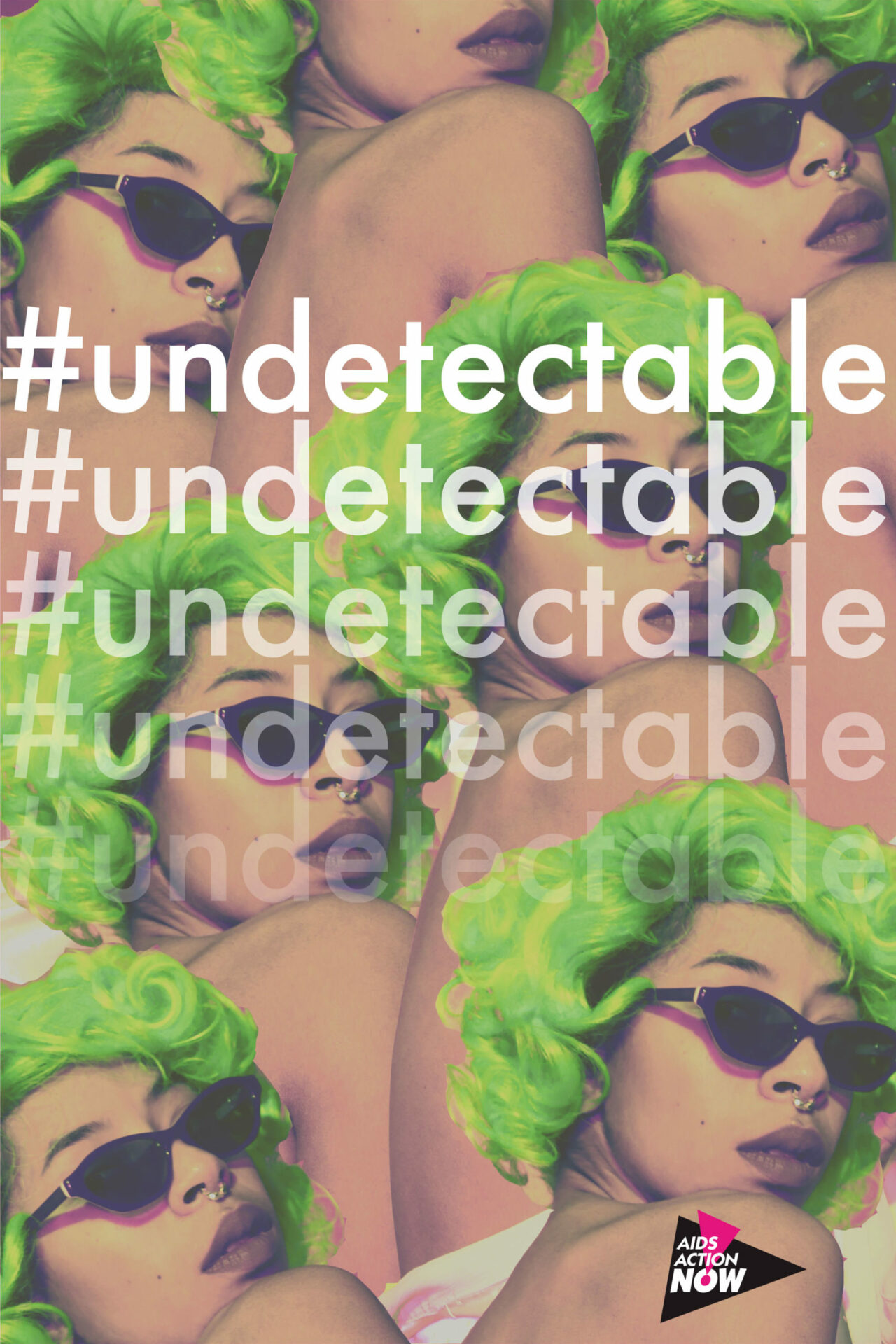

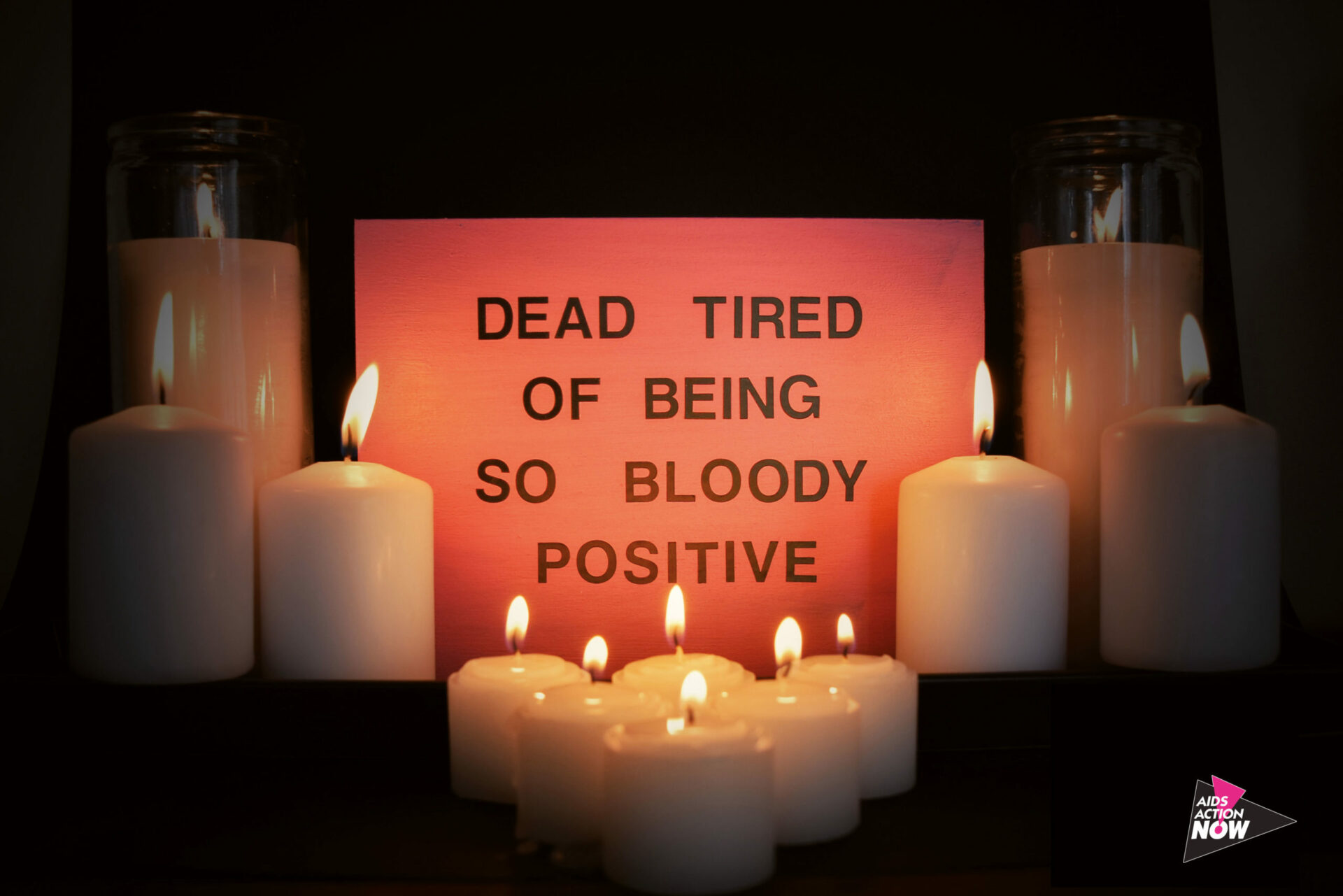

These dynamics are explored in both abstract and literal terms for the 2016 iteration of the PosterVirus project. For one of the six poster designs, Brendan Fernandes places a text banner that reads “In PrEP WE TRUST?” in front of a colourful background patterned with pills and roses. Fernandes’s strategic placement of the question highlights certain hopes and doubts that have become associated with new prevention therapy drugs such as PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) and PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis). Kia LaBeija’s #undetectable also tackles the social implications of recent advances in HIV treatment. Featuring a cluster of repeated headshots of the artist in sunglasses and Marilyn Monroe-styled green hair, this work addresses LaBeija’s own identity as an HIV-positive woman who has an “undetectable” viral load and is therefore no longer considered to be infectious. In Dead Tired of Being So Bloody Positive, Shan Kelley explores the issue of identity through an alternate lens. He stages a modest candlelit scene around a woodblock, with text that comments on the expectations placed on people living with HIV to present themselves as compliant and optimistic in public. Each of the six contributors has followed this general visual structure by creating works with bold graphics on which are superimposed thorny, strategically circular wordplay.

DEAD TIRED OF BEING SO BLOODY POSITIVE, 2016.

Photo : courtesy of PosterVirus

IN PrEP WE TRUST?, 2016.

Photo : courtesy of PosterVirus

Several major curatorial projects have emerged — most notably the travelling group survey exhibition Art AIDS America, originally presented at the Tacoma Art Museum in 2015 — that are focused on the issue HIV/AIDS and its lack of visibility in the Western art-history canon. McClelland and Whitbread take a different route, mapping out an alternative approach to queer curating, one that deliberately betrays traditional understandings of “queer” as a stable sexual identity category and “curating” as a creative practice that operates strictly within the space of the museum. This “undisciplined” approach to queer curating extends beyond the frame of gay and lesbian studies and academic art history. The curators do not merely attempt to insert works by and/or of HIV positive individuals into the space of the museum or the art history textbook. Reaching beyond insular, assimilationist historical readings of identity politics, PosterVirus embodies a significant methodological shift in curatorial practice away from the study of “queer actors” toward an interest in disruptive, unruly, and anti-normative “queer actions.”5 5 - Deborah P. Britzman, “Is There A Queer Pedagogy? Or, Stop Reading Straight,” Educational Theory 45, no. 2 (1995): 153.

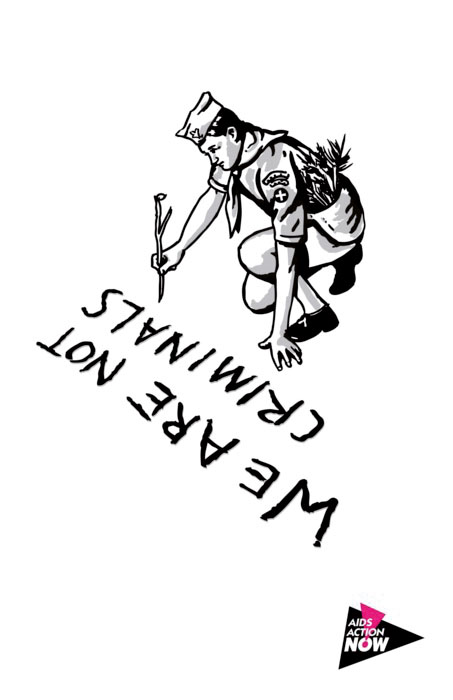

We Are Not Criminals, 2011.

Photo : courtesy of PosterVirus

Following the example of Gran Fury, PosterVirus investigates the ways in which society is founded on carefully crafted words and images that have the power to shape attitudes, behaviours, and responses.6 6 - Gran Fury, “Good Luck… Miss You.” One of the project’s central curatorial aims is therefore to disrupt the visual order of the city street by queering words and images that possess this sense of cultural authority. In the view of McClelland and Whitbread, this process of queering is based upon a rethinking of the social and spatial relational dimensions of art spectatorship. Accordingly, the poster installations can be understood as dynamic, productive sites that confront passers-by with images reflecting uncomfortable and inconvenient truths about the social politics of the virus as it stands today — in the sense of the medical reality that we are still without a cure, and moreover, in the sense that our society continues to partake in forms of violence against those living with HIV. In this state of coexistence and co-exposure, the city street is framed as an open, unsettled canvas in which queer relations are established and the public imagination is infected with the cutting message that our society is anything but post-AIDS.