[En anglais] I can see you now that my face is falling off my own face to make room for yours so we can see eye to eye and hear the voice of our hands touching Bruxelles at night – Maryse Larivière, 2015

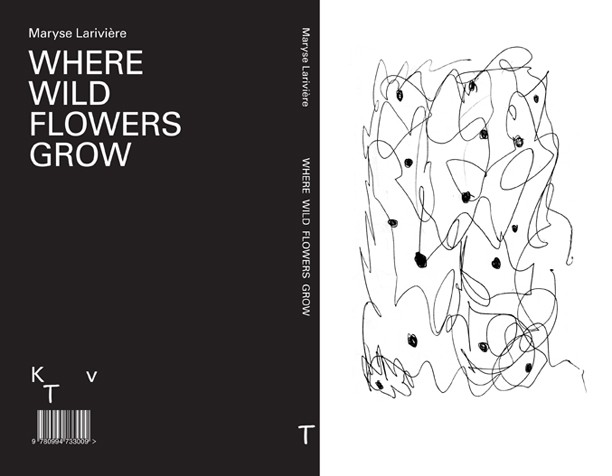

Produced in conjunction with an eponymously titled exhibition at Kunstverein Toronto (April–May 2015), Maryse Larivière’s Where Wild Flowers Grow is a decisively optimistic contemporary romantic trip. The book is a collection of poetry, prose, and discourse in which experimental, personal, and anecdotal forms of literary realism are used. Larivière’s approach to writing encourages multiple forms of reading. By treating text as both meaning maker and compositional tool, she ensures that Where Wild Flowers Grow is able to migrate back and forth between the worlds of the literary, theoretical, sculptural, and performative. The book’s twenty-five separate pieces of text are meant to be consumed more like movements in a symphony than chapters in a book. Some pieces are only three short lines long, others read like theatrical dialogue or personal anecdote, and still others are nothing more than brief statements printed near the top of an otherwise blank page. Where Wild Flowers Grow offers rare insight into the complexities of the artist’s innermost desires and provides readers with a physical sensation of reading. The book’s exterior silky matte finish is soft to the touch and there is a satisfying tactility to the weight of its heavy stock pages. Also including a series of minimalist gestural line drawings, the book is best experienced through an active letting go that allows rhythm, flow, and mood to merge with intellectual content.

Créez-vous un compte gratuit ou connectez-vous pour lire la rubrique complète !

Mon Compte