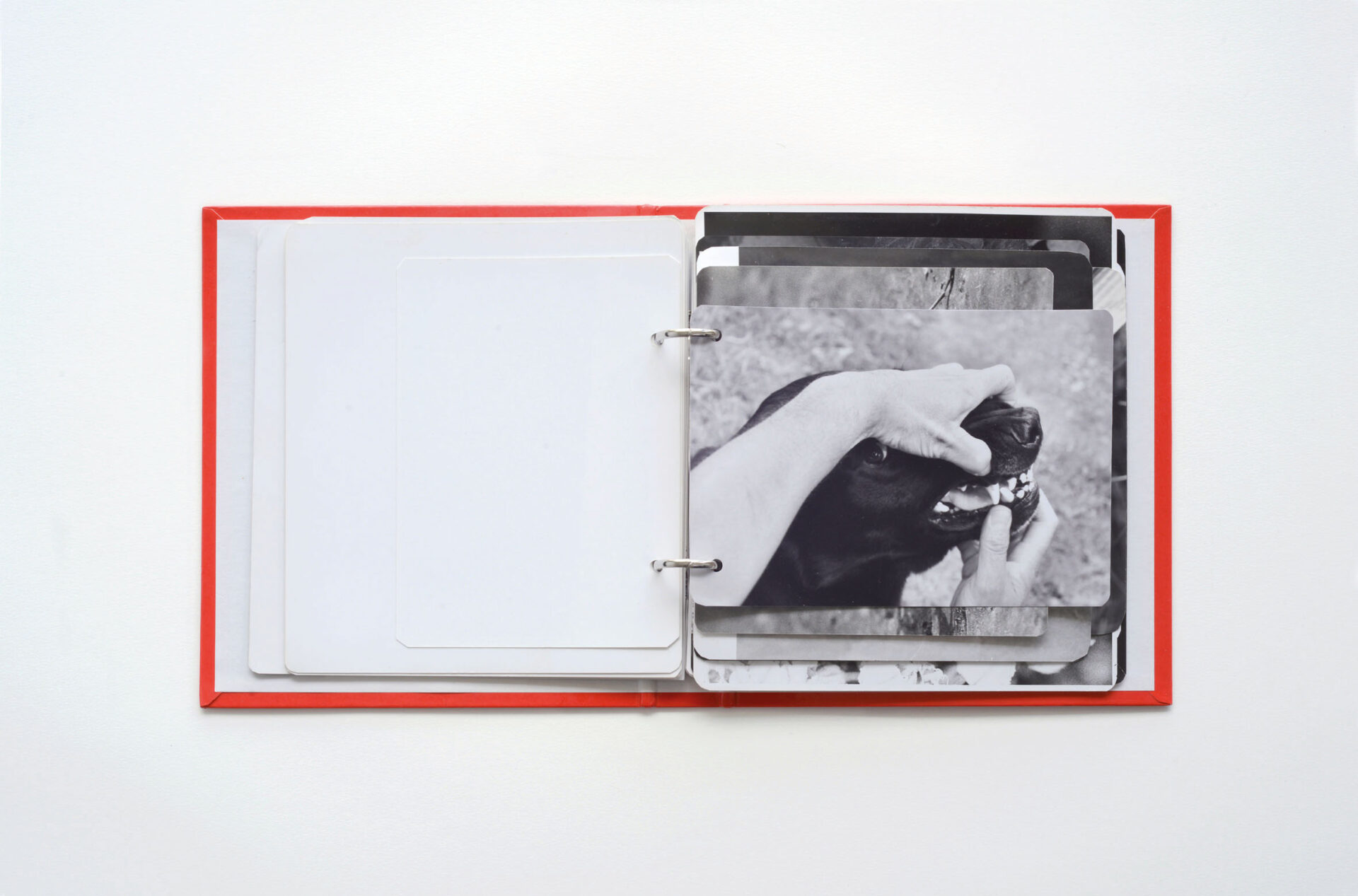

Photo: © 2018 Mike Di

Serpentine Sackler Gallery, London, U.K.,

March 6–May 20, 2018

March 6–May 20, 2018

[En anglais] The water is static. The water is in motion. The water courses neon purple, ultraviolet, with undulating waves. The water turns blue, green, grey, brown, red: murky and opaque with what appears to be blood, dirt, oil. The water covers the walls—wall-to-wall, corner-to-corner—a wash of waves in quadruplicate: four walls, a room of roiling colours and shapes, engulfing the space and its viewers entirely. Ambient noise fills the air: a serene soundtrack of echoes and faraway chimes, light melodies, or perhaps distant voices in song.

A calm before the storm? Yes, if the storm is a rising internal heat—a critical unrest that refuses to acquiesce and draws attention to that which bubbles and seethes beneath all surfaces. The word “typhoon” comes from the Greek tuphōn, whirlwind, and denotes a violent wind that has a circular motion. American artist Sondra Perry’s Typhoon coming on, her first solo show in Europe, is just that: apprehensible currents of activity in the air, ebbs and tides approaching, the atmosphere rife with disturbance—hints at the strong winds of change that are soon to descend, if you just carefully tune your eye and ear to a different frequency.

Créez-vous un compte gratuit ou connectez-vous pour lire la rubrique complète !

Mon Compte