Photo: Joe Maher, courtesy Getty Images

January 31–April 7, 2019

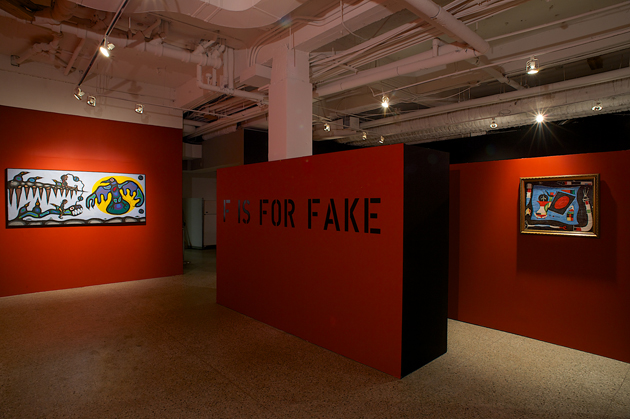

[En anglais] Inside the Curve, another curve: the wall bulges, convex, pushes us outward, squeezes our narrowing trajectory. The wall imposes upon us and alters our elliptical route. We walk along it; we walk and walk, and at various turns, things reveal themselves. In a small spotlit alcove, a black and white photo shows a sumptuously furnished domestic space. A door is open, leading to a balcony that overlooks hills that glow in the distance. Through the window, we see a small dark figure — slender: a woman? — with their back turned to us. This is the home that Daria Martin’s paternal grandmother, Susi Stiassni, was forced to flee as a teenager, to escape the Nazi invasion of Brno in 1938.

In the three-part installation Tonight the World (2019), this is where we find ourselves: with Susi, inside her childhood house, sometimes inside her mind. But where, exactly, this is, and what exactly is happening, is never entirely clear. Following the wall, further into the space, a large window is cut out of the curved expanse, through which we can see a wide grid of 265 typed papers fixed to the wall. Some of the texts are annotated, while others have rhizomatic sketches drawn alongside in the margins. Here and there, the papers are studded with brightly coloured Post-it Notes. This is an environment of esoteric, evocative signs and symbols. We can see, but we cannot touch. We can look, but we cannot read. We get closer, but we are still far away. It feels like we might be in a dream. Because we are. It’s just someone else’s.

Créez-vous un compte gratuit ou connectez-vous pour lire la rubrique complète !

Mon Compte