photo : © Yam Lau, permission de | courtesy of Katzman Kamen Gallery, Toronto

A few recent exhibitions in Montréal1 1 - Chris Kline, Galerie René Blouin, Montréal, 2008. Yam Lau, Galerie B-312, Montréal, 2011. Lynne Cohen, Art 45, Montréal, 2011. Nelson Henricks, Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen, Montréal, 2010. Lani Maestro, Fonderie Darling, Montréal, 2010. suggest that many contemporary artists continue to assert ambitious and innovative art practices rather than fleeing into tradition with its “well-made objects.” These exhibitions belong to “the contemporary” on the basis of their relevance to the questions we are bringing to them here, in this case questions pertaining to technics and its relationship to tradition. If tradition is a reference in contemporary art it is to the extent that post-historical or cyclical constructions of time and temporality are embraced. Some perspective on this question of tradition can be drawn from these recent works which present making, building, and viewing from the perspective of non-knowing, paradox, emptiness, and non-purposive behaviour.

It may be objected, however, that this perspective now belongs to the past, to an avant-garde movement now completed. This is the art historical view of avant-garde but an alternative exists in the conception of avant-garde formulated in historian Matei Calinescu’s argument that “avant-garde” is not primarily the name of a stylistic movement but refers to a mode of temporality that is open to the unforeseeable, to what is fundamentally incomplete.2 2 - Matei Calinescu, Five Faces of Modernity: Modernism, Avant-Garde, Decadence, Kitsch, Postmodernism. Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 1987, p. 95-148. [Trad. libre] His proposal leads to a construction of art viewing on a performative model.

Sarat Maharaj, a Duchamp scholar equally conversant with the craft and artisanal traditions, defended the “non-knowledge” of artistic activities in the face of dominant perceptions that “nothing counts unless it has the systematic rigour of ‘science.’” His argument against modelling art practice on scientific rigour rests on what he perceives as a need for activities that “resist being wholly taken under the wing of systematic methodological explication.”3 3 - Sarat Maharaj, « Know-how and No-How : stop gap notes on ‘method’ in visual art as knowledge production », Art & Research, vol. 2 (printemps 2009), p. 1-11.

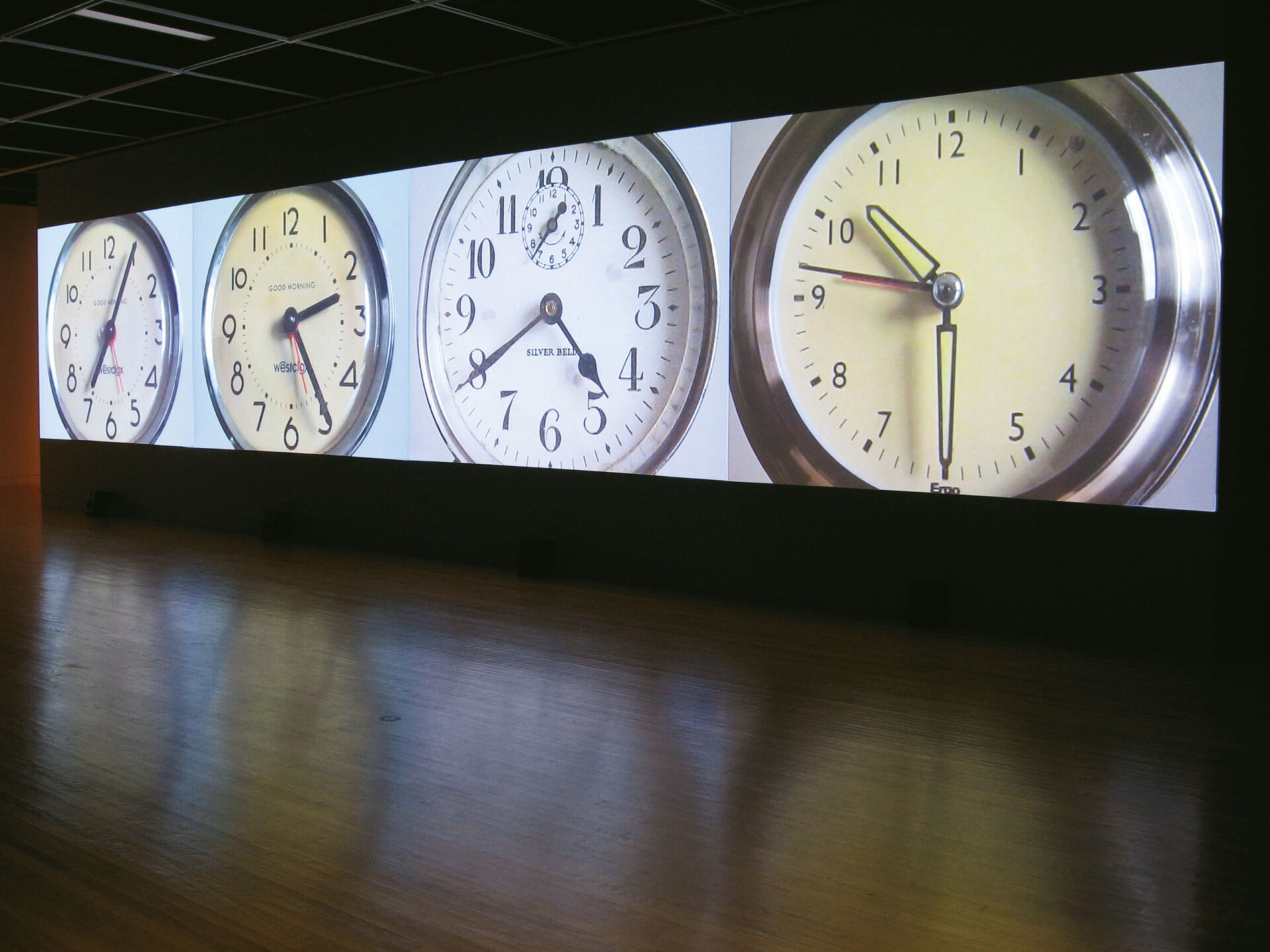

This topic of tradition and technics could be considered on the basis of almost any contemporary exhibition, however, a few seen in recent years in Montréal would be adequate. We could take a look at the simple yet sensuously resonant paintings of Chris Kline, bringing them to contrast with the computer-generated video animations of Yam Lau, who coincidentally began his art practice as a painter. These two artists make works of great refinement and are therefore susceptible to being described as “skillful.” Recent exhibitions by Montréal photographer Lynne Cohen equally emphasize enquiry into the status of building/making in the era of technical abstraction. A retrospective of video work by Nelson Henricks represented this artist’s preoccupation with issues of narrative construction and the existential conflicts between the temporality of the video medium and that of one’s own life. Finally, a glimpse at the installation by Lani Maestro at the Darling Foundry suggests further evidence of any “return to tradition” as paradoxical.

Fonderie Darling, Montréal, 2010.

photo : Guy L’Heureux, permission de | courtesy of Fonderie Darling, Montréal

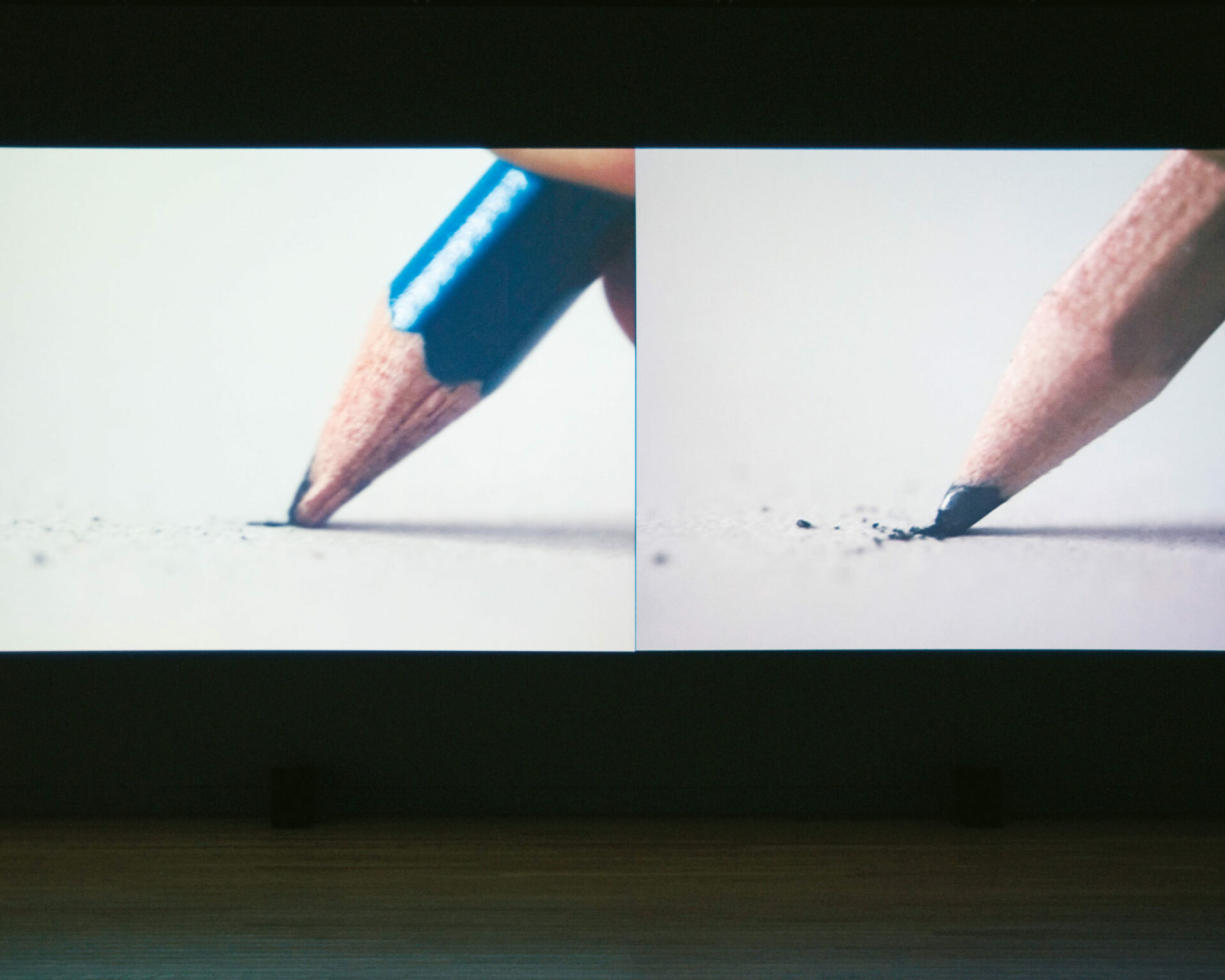

To describe a work of art as “well made” or “skilled” is usually to fall short of saying anything pertinent. Works of art “in themselves” propose not the hierarchical vocabulary of the “well made” but the anarchical “well-enough-made.” Nelson Henricks’s video retrospective held last year at the Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery at Concordia University presented a number of video works narrating, as subject matter, Henricks’s own struggle to write for video. The arbitrariness that results from immersing oneself in contingency as a source leaves the artist with the task of sorting through memory and its attachments and disconnections in the social or historical milieu. Writing as a performative task as Henricks formulates it is a kind of Proustian quicksand with which one engages in the search for artistic form. From this perspective the notion of well-made art looks absurd or at least, anomalous. As an everyday art critical concept, “well made” at least requires further and very precise contextual elaboration if it is to be meaningful. I might think of a shirt as “well made” if the stitching is tight, the fabric durable and the design to my liking but would I ever spontaneously describe an artwork as “well made” unless I were speaking ironically, or in a context in which the phrase would be understood as a casual generalization?

photos : © Paul Litherland & Nelson Henricks, © Paul Smith & Nelson Henricks; permission de | courtesy of Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen, Université Concordia, Montréal

These perceptions arise the moment we encounter Lynne Cohen’s photographs where “making” consists of documenting a play between virtual and actual space, a play revealing their reciprocal and complementary status. French critic Marie de Brugerolle has called Cohen’s path a “metaphysical investigation. . . guided by clues,” asking also, “what are we to make of the strangeness that is the subject of these images?”4 4 - Marie de Brugerolle, Lynne Cohen, (ed.) France Choinière (Montréal: Dazibao, 2011): 6. Descriptions of Cohen’s photographs often stress terminologies both spatial and temporal, with the favoured terms being “transitional,” “temporary,” “artificial,” and “alienating.” “Veneer” is a word that comes up frequently and the manufacturing process by which veneers are made is particularly relevant to our consideration. Veneer is often produced using a photographic process to replicate wood grain, substituting a superficial image for a tactile material. It also comes into play as a metaphor attached to attitudes and behaviours or even to describe contemporary practices of dwelling. Veneer implies “covering over,” and art such as Cohen’s often serves to point out that what has been covered over is the uncanny thing, the strange returning in the guise of something familiar. In relation to the topic of “making” Cohen’s photographs present insights into how our current building practices present a fullness that is virtual and that is as empty as it is full. The interior rooms that are always the subject of her photographs present not a damning sociology of current design, but rather, consist of observations toward our contemporary design practices which no longer oppose the virtual to the actual, where full may also mean empty and vice versa.

Lynne Cohen, Untitled (Windows), 2010.

photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of

the artist & Art45, Montréal

Yam Lau’s computer-animated video installation Rehearsal at Galerie B-312 last spring would seem to be a good example of a skilled use of digital visual production technology. In this video Lau begins with a schematic rendering of a view from “outside” into the “interior” of a built space. Two modes of viewing are initially proposed: we see the schematic animation, but also the integration of images of an “actual” room with a real occupant. This interior “takes place” in the ongoing imaging process which inhabits a stage-like space that rotates, and while rotating, shifts views through transparent veils of animated architectural rendering. I used the adjective “skilled” just now to refer to this work but where is the skill and what is this artist’s relationship with it? Could we not locate this skill within technics itself rather than in the artist’s use of it? What I suggest is that Lau’s process actually deconstructs “the skill dimension” of the computer video animation that is embedded in the technology. By layering multiple viewpoints and visual modes he takes apart whatever we might think of as technical sophistication, substituting for it a gentle and meditative proposal regarding our inhabitation of place.

Genuine works of art often act by incorporating non-art entities and materials into their own workings. Even if this became explicit with early Modernist works such as Degas’s Little Dancer of 14 Years or Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning, or the fragmentation of various traditional procedures such as bronze casting (fragmentations such as Medardo Rosso’s refusal to take his wax models to their final step toward permanence); the history of this notion could be pushed back beyond the days of Modernism’s inception. The artworks I am discussing embrace this tendency toward an incorporation of non-art materials and practices along with aspects and fragments of artistic and artisanal traditions in order to reflect on contemporary modes of “making.”

For example, Chris Kline’s paintings shown at Galerie René Blouin in 2008 make fragile woven cotton fabric an explicit concern, an apparently simple material pushed to an extreme, and the same may be said of the work’s facture. In this particular series Kline’s paintings have no paint on their surfaces at all, simply a single line drawn (sewn) horizontally, forming a seam that joins two subtly different fabrics. The simplicity of these elegant works reinforces the attention given to the seam, the drawing (pulling inward) that the stitching makes, and the joining together it accomplishes. In such a reduced work like this, tension is everything, and tension is not an object but an encounter with the rhythm of perception itself. Tension is now: tension is the gap about which Duchamp wrote, “it’s not what you see that is art, art is the gap.”5 5 - Marcel Duchamp as quoted by Arturo Schwarz. The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, 2nd rev. ed. (New York: Abrams, 1970), 197. In Kline’s “paintings” this tension is the felt sense of the joining, the being held together in the breathing of inside and outside, above and below. Kline’s seams look merely “well-enough” made without attempting to demonstrate virtuosity of crafting or technique. Skill is largely bound up with issues of control whereas what we see in works of art such as Kline’s, is care. Control is rigid behaviour directed by the dictates of means and ends efficiency, but care is ultimately a concern for time, not only in terms of mortality but for the dimension of futurity. From a Duchampian perspective (the relationship of art and life modelled on breathing), works of art would consist of “letting go” rather than an exercise in control.

Chris Kline, Rim, 2008. (bas | bottom)

photos : © Richard-Max Tremblay / SODRAC (2011), permission

de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist & Galerie René Blouin, Montréal

Chris Kline, Rise, 2008. (bas | bottom)

photos : © Richard-Max Tremblay / SODRAC (2011), permission

de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist & Galerie René Blouin, Montréal

In 2010 Lani Maestro, in collaboration with composer/violinist Malcolm Goldstein created the site work l’oubli de l’air, at the Darling Foundry in Montréal. This apparently simple installation covered the Foundry floor with a black sand surface punctuated at random intervals by reflective pools of water registering the passing of sky and clouds from the overhead clerestory windows. Obviously a different sort of work from that of Yam Lau or Chris Kline yet there is a similar interest in discerning building/making in terms of a play that redefines the opposition of inside and outside, or the empty/full. Such a play is remarked on by Anja Bock who wrote, “didacticism would be an imposition and a constraint on the work’s poetic logic, which opens a far more expansive, if less easy to define, territory.” She goes on to say, “its materiality and music wraps itself around us to the point of rendering us immobile, caught in the spell of its most modest monumentality. It is as if the vast hollow space of the foundry is full, so full that it does not allow time to enter.”6 6 - Anja Bock, “Lani Maestro: l’oubli de l’air,” BorderCrossings (March, April, May 2011): 80–81. However, in this installation the tradition and the practice of sculpture have not defined the work stylistically but simply exist as threads among others from which the work weaves, ultimately leaving us, as Bock has written, “with our intellectual handles and habitual ways of being (now) unanchored.”

Artworks such as those discussed here engage with our building and dwelling practices, with issues of making, of materials, and their virtuality such that the interpenetration of each with its other is reciprocal, reversible: materiality becoming virtual and the pictorial/virtual revealed as a bodily materiality. These artists and exhibitions present diverse investigations of spatial and temporal construction in which non-knowing, emptiness, and the unforeseeable are privileged modes of being and doing destined to perpetually undermine the realm of skill, know-how, technique — all the behaviours that belong to the realm of pre-determined goals and the criterion of “efficiency.”