No government in the world in the age of digital citizenry is immune to the indignation of its citizens.1 1 - Peter Sloterdijk, Repenser l’impôt: Pour une éthique du don démocratique, translated from the German by Olivier Manoni (Paris: Libella/Maren Sell, 2012), 307 (Our translation).

The title of this essay alludes of course to Kasimir Malevitch’s famous White on White, produced in 1918, which makes manifest the end of representation in art as well as the desire for an absolute that equates with nothing, with the un-objective, the non-figuration of objects. It wasn’t alone, as the Russian artist produced a whole series of painted squares, including Black Square and his famous Red Square. For Malevitch, these suprematist paintings heralded a new beginning.2 2 - Kasimir Malevitch, Le miroir suprématiste, translated into French by Valentine and Jean-Claude Marcadé (Lausanne: L’âge d’homme, 1977). Coming about through painting, suprematist formalism was part of an aesthetic conception of the world, the symbol of a revolution at once spiritual, economic, and political in nature. And yet, artists' contributions to the development of a social conscience focused on the present remained problematic throughout the twentieth century. The questions raised by this movement seem just as relevant today: How can artists participate in the revolution through their work, specifically as cultural producers, not merely as individuals? How can artists foster aspirations for change through their work? Can the spectators of their work become actors within a community of citizens? While the avant-garde pictorial revolution of the last century was sidelined by the Marxist-Leninist political revolution, perhaps artists’ free thinking found more promising paths in theatre? In this respect, Alexis, una tragedia greca, presented at the Festival TransAmériques (FTA) in Montreal,3 3 - Sixth edition of the Festival TransAmériques, held from May 24 to June 9, 2012. provides some interesting avenues for reflection.

Alexis, una tragedia greca is the last segment of a series titled Syrma Antigónes, composed of four theatrical performances by the Italian theatre troupe Motus, which presented two works at the FTA, Too Late [Antigone] contest #2 at Espace Libre and, of course, Alexis at Cinquième Salle. The latter is based on the death of Alexandros Grigoropoulos, a 15-year-old teenager who was shot by a policeman during a demonstration in Athens on December 6, 2008. Like many young students, he had come to protest austerity measures, particularly related to education, that were part of the government’s response to the unprecedented financial crisis. His tragic death sparked the general public’s indignation. Several days of riots ensued in which students and anarchist groups confronted the police. Demonstrators were naturally reacting to police brutality, but they were also protesting the injustice caused by a financial capitalism that, in crisis, had forced the democratic State to lend it credibility.

Based on the crime committed by this police officer and on a socio-economic crisis that falls hardest on the destitute, Motus co-founders Erico Casagrande and Daniela Nicolò conceived of a play that takes place on a stage painted with an immense red square. And since the events took place in Athens, they also drew inspiration from Antigone, who remains a central character throughout the four-show series. It is mainly Bertold Brecht’s adaptation of Sophocles’ play that led Casagrande and Nicolò to make the Greek heroine a symbol of resistance against Creon’s arbitrary power. In the context of the 2008 riots, they also equate Alexandros’ death with that of Polyneices, and Antigone herself with the revolt of thousands of innocent victims of an economic system presented as an inevitability. One may certainly question the authors’ association of the three As — Alexis, Antigone, and Anarchy. One may wish for a more nuanced perspective. But in light of what has just been said, I would like to explore something different here, something, in fact, that is hinted at several times by the play’s protagonists, some of whom use a video projector to screen images of the location where the homicide took place. As in an investigation, they present us with the facts. They show the Exarchia neighbourhood, where posters and slogans with battle cries line the walls. Members of the audience can thus readily identify with the actors who have become spectators of a prior event. Faced with the recent tragedy, the spectators become actors of sorts, thus blurring the demarcation between what usually marks the stage, where the show takes place, and where the audience sits. Questions then arise concerning the artist’s role. Questions that also prompt spectators to ponder what theatre can provoke in such circumstances.

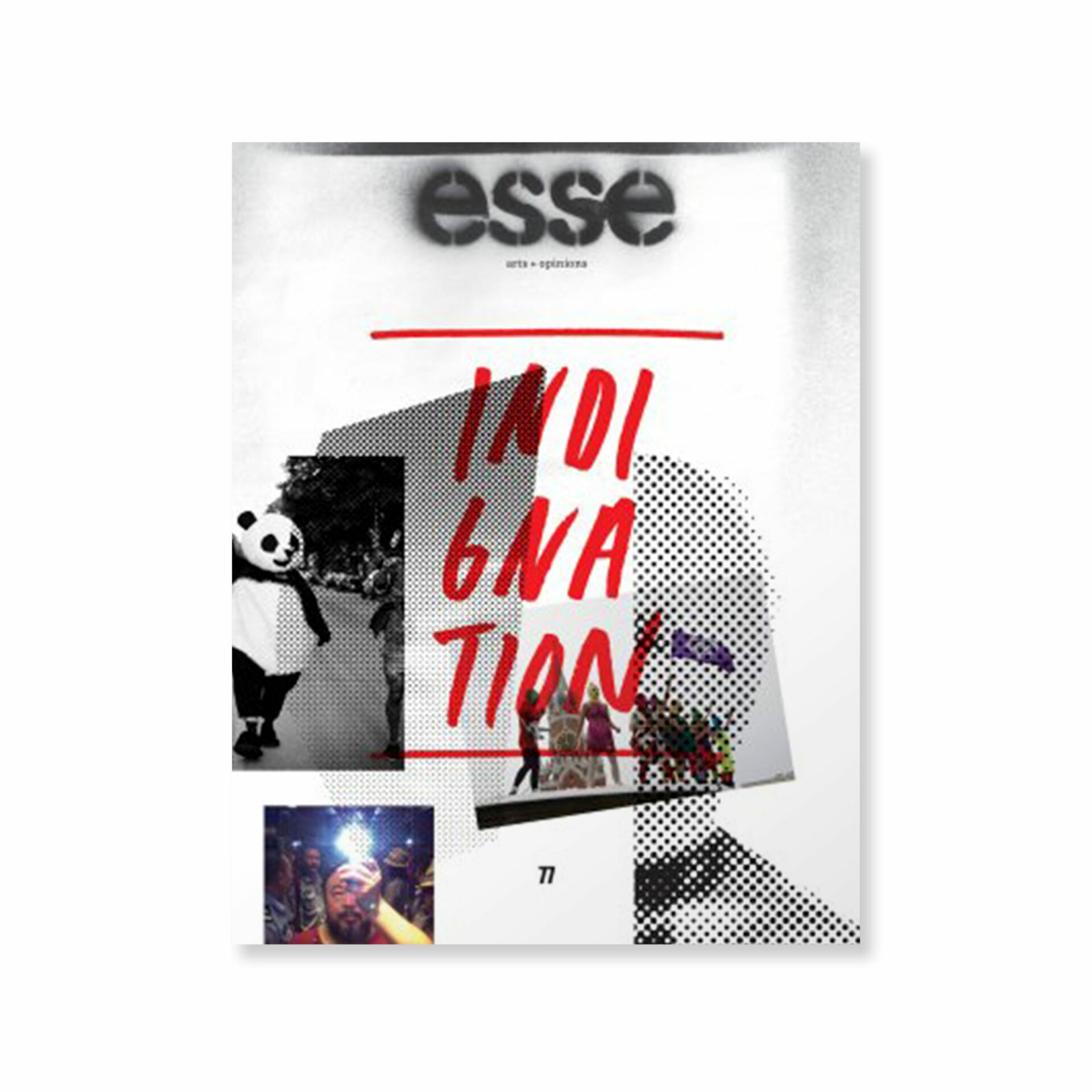

photo : © Valentina Bianchi

In the artistic sphere, modernity developed from a dichotomy between an aesthetics of reception and an aesthetics of production. That dichotomy is what gave rise to the crisis regarding art’s social function in public space. Nietzsche clearly expresses the distance between spectator and actor when he amplifies the creativity of the artist as opposed to the tastes of the common man. The opposition was further exacerbated with the emphasis of the spectator’s passive role in an entertainment-based society. Spectators are not players; they contemplate the show, which they may judge because they are outside the action. In this conventional perspective, spectators watch and their judgement of the show remains disinterested. Yet this paradigm is challenged in the visual arts, as it has long-since been in theatre as well. All of modern theatre, starting with Brecht and Artaud, has striven to break the barrier between actor and spectator. Epic theatre, in particular, questions the merely recreational aspect of a theatrical representation. It denies the separation between a spectatorial aesthetic and a creative one. It is not addressed to a passive spectator who looks on without reacting; rather, it assumes that spectators are involved. If entertainment, as Guy Debord explains, separates us from a sense of community,4 4 - Guy Debord, La société du spectacle (Paris: Éd. Gallimard, coll. Folio, 1992). theatre is not mere entertainment. It is precisely this political role of theatre that Jacques Rancière references.5 5 - Jacques Rancière, Le spectateur émancipé (Paris: La fabrique, 2008). In theatre, more than any other art form, there is a desire to connect with the “romantic idea of an aesthetic revolution.”6 6 - Jacques Rancière, op. cit., 12 (Our translation). Thus, alongside Malevitch’s suprematism, avant-garde theatre wishes to establish a stage that solicits the spectator’s intelligence. It is addressed to a spectator who is aware that theatre can also be a mirror to what is taking place on the political scene, where the real issues of life in society are being played out. Consequently, spectators — the “spectactor” as Christian Ruby puts it7 7 - Christian Ruby, L’archipel des spectateurs (Paris: Nessy, “La philosophie aux éclats,” 2012), 152. — recognize themselves as citizens, citizens who have no choice sometimes but to be outraged.

Outrage, or indignation, comes up frequently in the Syrma Antigónes series. In Alexis, though, the authors bring us face to face with the outrage of a people in the grip of a capitalist financial crisis. From this perspective, Antigone’s character is a prime figure of indignation. Thus, toward the end of the performance, the actors propose new images of recent demonstrations, above all those of outraged Spaniards, Greeks, and Americans from Occupy Wall Street. And since performances of Alexis were seen in Montreal during its “Maple Spring,” images of students demonstrating against tuition hikes were also added to the mix. Given the political necessity for solidarity, after the screenings, as if to show that public outrage cannot be left in the hands of a passive audience, one of the protagonists invited spectators to climb onto the stage. As she did so, she wondered what it would be like if we were more than two, or three, or four, and so forth. The first to come out of the shadows were her own colleagues, but then members of the general audience spontaneously answered her call. Five, ten, twenty, thirty people enthusiastically joined the others, and minutes later close to a hundred people were on stage. Among them, many wore the red square, which, for the remaining audience members, created the image of red squares on red background.

Even if the art of participation is chiefly practised in a theatrical framework, this performance seeks to question the opposition between actor and spectator. By demonstrating that real action is possible, Alexis gives us signs of hope; it instills the idea that the passive spectator can change. But for this to happen, indignation, even in its representation, must reach beyond the theatre. The moral sentiment is initially disruptive, it also instills anger. Yet, if we are to reconsider global capitalism’s hold on our democracies, indignation cannot limit itself to this anger. Antigone’s anger is of the order of an ethos, a spectacular ethos that Sophocles brilliantly transposed to theatre. As such, while indignation evolves on a backdrop of anger at injustice, it also draws strength from the hope of living humanely. Faced with injustice, indignation thus questions what is most worthy in humanity. Only in the modern era, writes Jean-François Mattéi, has indignation become the prerogative of everyone. Only in the age of the rights of man have philosophers engaged in reflections that could place value on the human beings we are.8 8 - Jean-François Mattéi, De l’indignation (Paris: La Table ronde, “Contretemps,” 2005).

The age of indignation, then, is intrinsically modern, contemporary with the advent of aesthetic modernism, precisely that which leads to the passive spectator’s aesthetics of taste — an aesthetics that can also lead to disgust (or distaste) before particular spectacles. If there is indeed a sign of hope in Alexis, if there is a desire to question the economic sense within our democracies, this hope cannot remain mere indignation. It must outgrow Antigone’s anger. And while indignation may seem to take precedence these days, it must not be transformed into resignation. It must thoughtfully transform itself into a fight for dignity. In this sense, indignation must transcend vengeance and resentment.9 9 - Peter Sloterdijk, Colère et temps: Essai politico-psychologique, translated from German into French by Olivier Manoni (Paris: Hachette, 2007). It is a lesson Albert Camus teaches us as well; at the start of L’homme révolté, he writes that the rebel is one who not only refuses but who also says yes.10 10 - Albert Camus, L’homme révolté (Paris: Gallimard, 1951), 25. In other words, the rebel is a spectator who dares become the actor in his or her own life.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]