Photo: courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris

In the same way that the idea of the “performative,” borrowed from J. L. Austin’s linguistic pragmatics, entered the performing arts in order to account for certain practices while simultaneously demonstrating the limitations of the détourné use of the theory, the idea of re-enactment has acquired a preponderant place in some works of contemporary art. Its possible applications have similar limitations. These works are replays, remakes, reconstructions, reactivations, and restagings of performances or actions, whether done by the creators themselves or by some third party. Assuredly, the term re-enactment signifies re-making, re-playing or re-acting (performing an act again); and replaying Kurt Schwitters’s Ursonate or Oskar Schlemmer’s ballets is, in this sense, simply banal; one might not understand all the fuss about a mere change of label. Thus re-enactment makes a claim to something beyond re-playing or re-making what has already taken place. Of course, the difference is sometimes minimal, even indiscernible; one might not notice any change between Ursonate replayed and Ursonate re-enacted. In fact, it is a mere interpretation, an umpteenth version of the work, of the kind that has been done for ages. If to “enact” means to play, to represent on stage, to hold a role, logically re-enactment would be to reprise what has been played or represented. The main flaw in this use of re-enactment is that it obliterates the historical modification that doing so imposes on events, on perceptions and interpretations of the factual reality of art history. Restricting oneself to just a re-performance, in the philosophical sense of the term, without setting the aesthetic and artistic effects in their historical perspective, is a pretty poor showing. The presentation of a construction of Josephine Baker’s house (designed by Adolf Loos) as a re-enactment of an object (Ines Weizman/Andreas Thiele, 2008) in Mythologies of Re-enactment at the Royal Academy of Arts was a trick of language, despite its being an architectural success. The announcement read: “The process of re-enactment — the act of restaging a performance or recreating an object — is central to how the past can be interpreted. Re-enactments transmit memory, yet also inevitably lead to its alteration with the creation and propagation of mythologies.”1 1 - http://www.royalacademy.org.uk/architecture/future-memory/mythologies-of-re-enactment,1961,AR.html Yet reconstructing a building or remaking or remanufacturing an object is not a re-enactment. It is, precisely, reconstructing, remaking, or remanufacturing the object, period. What does this notion of re-enactment really add, since the very claim that its function is to transmit memory, even if modifying or interpreting it, can be made of any document, monument, or object from the past?

In the end, the term re-enactment has been made so extensible that it seems applicable to almost any work of art involving some kind of reprise; this both clarifies and further confuses the notion, since not everything involving a “re” automatically translates into re-enactment. For example, it seems difficult to think of Pierre Ménard’s project, imagined by Borges in his story “Pierre Ménard, Author of the Quixote,” as a re-enactment, since, according to the fiction, even though Ménard rewrote Cervantes’s novel down to the last comma, he is nonetheless the author of a work that is ontologically other and different, and not the same work simply rewritten, reproduced, or recopied by him. This is an important distinction — a recognition that re-enactmentimplies a reprising consequent to the same thing having already been done. In this sense, Ménard does not remake Quixote, he writes another novel.

Closer to our concerns, artistic re-enactments of more or less serious, violent, or important historical subjects often divert the idea of what they really signify, as was first suggested by English philosopher and historian Robin G. Collingwood. In all that is written or said about art, few authors refer to his book The Idea of History (1946), which contains a number of chapters2 2 - Robin G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (1926-1935), Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1994 [1946]. See, Epilegomena, 4: “History as Re-enactment of Past Experience.” dedicated to the problematic of re-enactment. In Collingwood’s view, it is not only impossible to “re-perform” facts or events, but, beyond that, a re-enactment deals with the ideas, thoughts, and concepts of history’s actors and not with the facts. We cannot have any empirical knowledge of the past; the witnesses are not reliable and the knowledge available through copies and reproductions is limited. What took place cannot, in any rigorous way, be redone — “What’s done cannot be undone,” as Lady Macbeth said. When Collingwood defends the re-enactment, it is, for him, a question of re-thinking the ideas and conceptions of the past and, above all, reading them critically, making value judgments, and bringing forward historical proofs of what we are claiming. The re-enactment is thus a historical operation that critiques, judges, and ultimately modifies the past as it is apprehended in the present; it is likely to modify the present and the future of history (and not only art history). In his re-enactments (The Battle of Orgreave, 2001), Jeremy Deller is perfectly aware of such stakes, but this is not the case for a great majority of artists who confuse “re-enactment” in Collingwood’s sense with a simple, banal “remaking.” Repeating, documenting, verifying, reinterpreting, citing works or history — these processes have been practised since art became art; we did not wait for the term re-enactment to be adopted in contemporary art circles to reperform or reconstruct works.

The Battle of Orgreave, 17 juin 2001.

Photos : permission de l’artiste et Gavin brown’s enterprise

The term re-enactment (generally translated into French as réexécution or reconstitution) is not synonymous with remake; this is explained by the presence of the word “enactment,” which is defined as acting, depiction, performance, personation, play-acting, playing, portrayal, or representation. It may be the representation of an action and, as regards re-enactment in Collingwood’s sense, the reprising of that representation of an historical event in a different context and situation, which could, nonetheless, be understood simultaneously as past events and as actualized, actualizable events. Collingwood’s conception has nothing in common with the spectacular, kitsch remakes by innumerable fantasy re-enactment associations in various countries — the London Riot Re-enactment Society and the Bosworth Battlefield Anniversary Re-enactment in the U.K.; the Re-enactment of the Battle of Stoney Creek in Canada — or the European associations staging Napoleon’s battles or those of the Legio VIII Augusta (Eighth Roman Legion). In chapter 4 of this book, titled “Epilegomena” (“Chosen Things”), Collingwood explains that the historian works on thoughts and actions more than on events, which are interior and exterior: “An action is the unity of the outside and inside of an event.” And, “For history, this object to be discovered is not the mere event, but the thought expressed in it. To discover that thought is already to understand it.”3 3 - Ibid., p. 214. The only way that the historian can understand past thoughts, in Collingwood’s view, is “by rethinking them in his own mind.”4 4 - Ibid., p. 215

Collingwood also insists that the “re-enactment of past thought is not a pre-condition of historical knowledge, but an integral element in it.”5 5 - Ibid., p. 290. To reach this conclusion, he compares the historian’s imagination to an artistic process, which is less surprising than it seems when one remembers that he wrote an aesthetic essay, Principles of Art (1937), in which he accorded enormous importance to the imagination. “As works of imagination, the historian’s work and the novelist’s do not differ,” he explains in The Idea of History. “Where they do differ is that the historian’s picture is meant to be true. The novelist has a single task only: to construct a coherent picture, one that makes sense. The historian has a double task: he has both to do this, and to construct a picture of things as they really were and of events as they really happened.”6 6 - Ibid., 246. The historian must therefore follow three “rules of method”: “First, his picture must be localized in space and time. . . . Secondly, all history must be consistent with itself. . . there is only one historical world. . . . Thirdly . . . the historian’s picture stands in a peculiar relation to something called evidence.”7 7 - Ibid. Thus a re-enactment of the past must meet several requirements and take place under certain conditions; notably, it must distinguish fictional claims from historical truth.

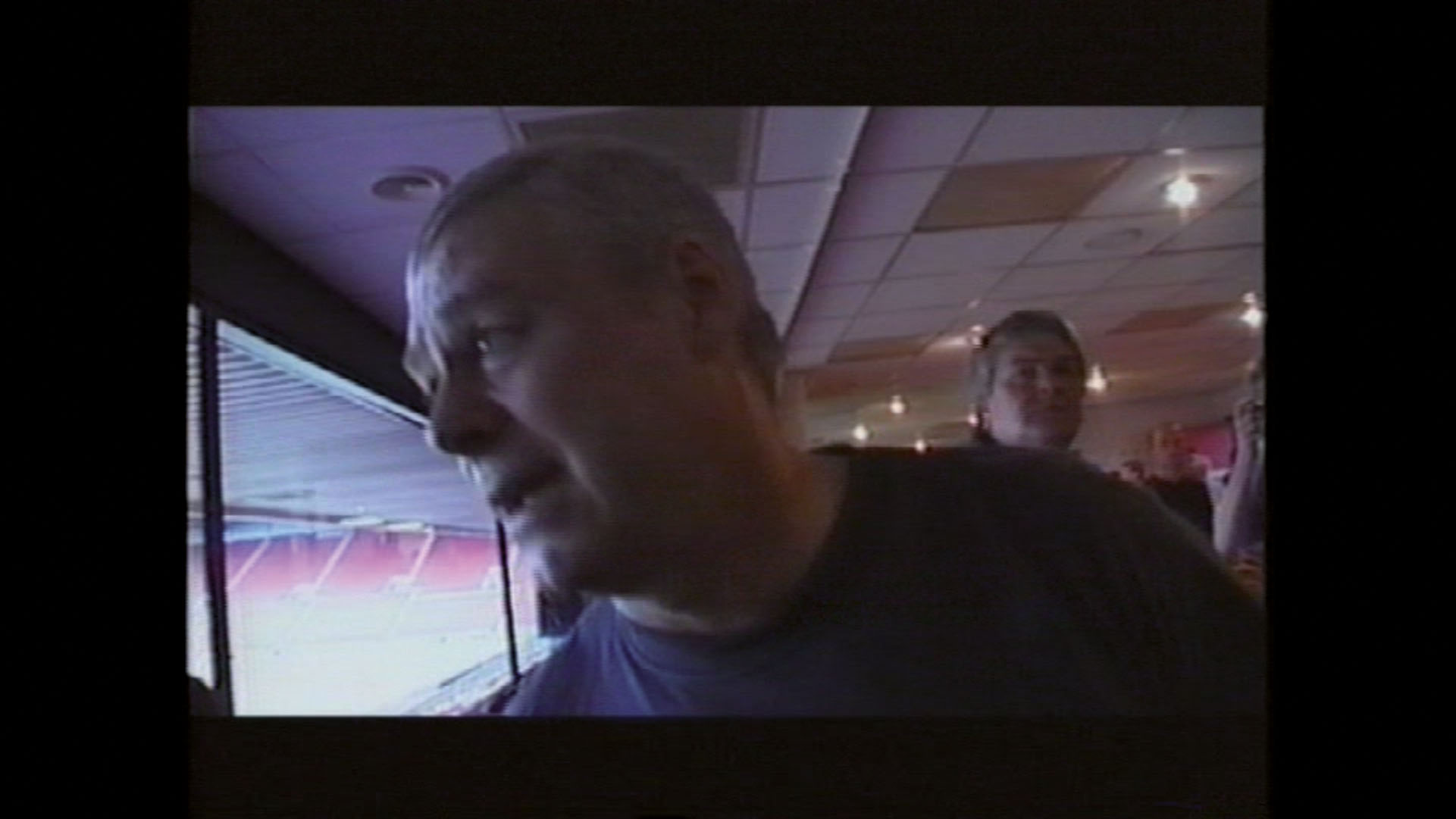

The Third Memory, videostills, 2000.

© Pierre Huyghe / SODRAC (2013)

Photo: courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York / Paris

Faced with such questions from historians, many contemporary “documentary-style” artworks offer to let us relive the past through a process of anamnesis. These works, more or less fictional — as they integrate real documents and documentaries — may affect the events’ temporality, which is modified and transformed by this sort of reprising. Pierre Huyghe’s work The Third Memory, presented at the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1999, is very instructive in this regard. It is largely a documentary re-creation of a fiction, Sydney Lumet’s film Dog Day Afternoon (1975), itself based on a real event: John Wojtowicz and Salvatore Naturile’s armed bank robbery and hostage-taking in an attempt to get the money needed for Wojtowicz’s partner’s sex-reassignment surgery. The attack, broadcast live on television, ended in failure: Naturile died and Wojtowicz was imprisoned. Huyghe’s installation included period documents, posters, press clippings, and an excerpt from a television program featuring Ernest Aron (the protagonist’s boyfriend, who had since become Liz Debbie) and John Wojtowicz, who have shared a duplex since the end of his prison term. In another room, the artist’s studio reconstruction of the attack was screened; John Wojtowicz played himself and explained what really happened. The film, a double projection, is intermittently accompanied by sections of Lumet’s fiction film. The set is a reconstruction of the interior of the bank, and the hold-up man himself, seen free years later, is replaying his words and acts. The entire installation primarily seeks to re-establish some truths, which, according to Wojtowicz, detracted from his actions, notably the idea that he sold out his accomplice to the police (which is untrue). The most surprising thing is that, using Huyghe’s docu-fiction work, Wojtowicz wants to establish the truth of Lumet’s fiction, which in the end is neither true nor false, because it is a fiction. Even if inspired by fact, it remains a pure invention. The Third Memory is thus at the crossroads of the documentary reconstruction of facts, gestures, words, spaces, and of the fiction and the actual and real presence of the protagonist rethinking and replaying certain moments. The ensemble manages to become another kind of memory, a third memory, delivering one possible version of the tragedy in which proof and truth, judgment and critique are brought together without the artist claiming to provide a complete resolution or exhaustive monstration of what happened.

In this kind of work, reprise, re-creation, and reconstruction are a form of re-enactmentin that they act on history and, no matter how precise, are not mere reconstitution, copy, or reproduction of other events and contexts. This reprising of an event produces, in turn, another event by being a re-enactment. Therein lie the real stakes of re-enactment, as many more or less successful attempts ( including the Center for Historical Reenactments in Johannesburg; the exhibition History Will Repeat Itself: Strategies of Re-enactment in Contemporary Art, at the KW Institute of Contemporary Art in Berlin; and Warren Neidich’s work, American History Reinvented) transform history, interpret it for better or worse, and risk falling over into partisan manipulation, becoming corrupt, false, or revisionist. The rules articulated by Collingwood should be a rampart against such possible diversions and false uses. If the re-enactment tries to produce truth, at least to a degree sufficient to its not becoming a fiction or purely imaginary reconstruction, the events represented must have some value, reflect some knowledge, and be presented in a form that does not falsify prior events. In his definition of re-enactment, Collingwood subtly makes it the thought of a thought in the present, in that the event is not prior to the thought, even if it is so chronologically. It is immanent to the thought being thought in the here and now, and it takes form and existence as an event only because it is thought. An event that is never thought, much less rethought, can neither take place nor appear as such. That such a thing, action, state, or fact is perceived as an event is the proof in action that it takes form or existence only in the thought rethinking it. Re-enactment, thus, can be seen as a return to the past with an actualization in the present and an indeterminate future, for it is always subject to re-creation.

[Translated from the French by Peter Dubé]