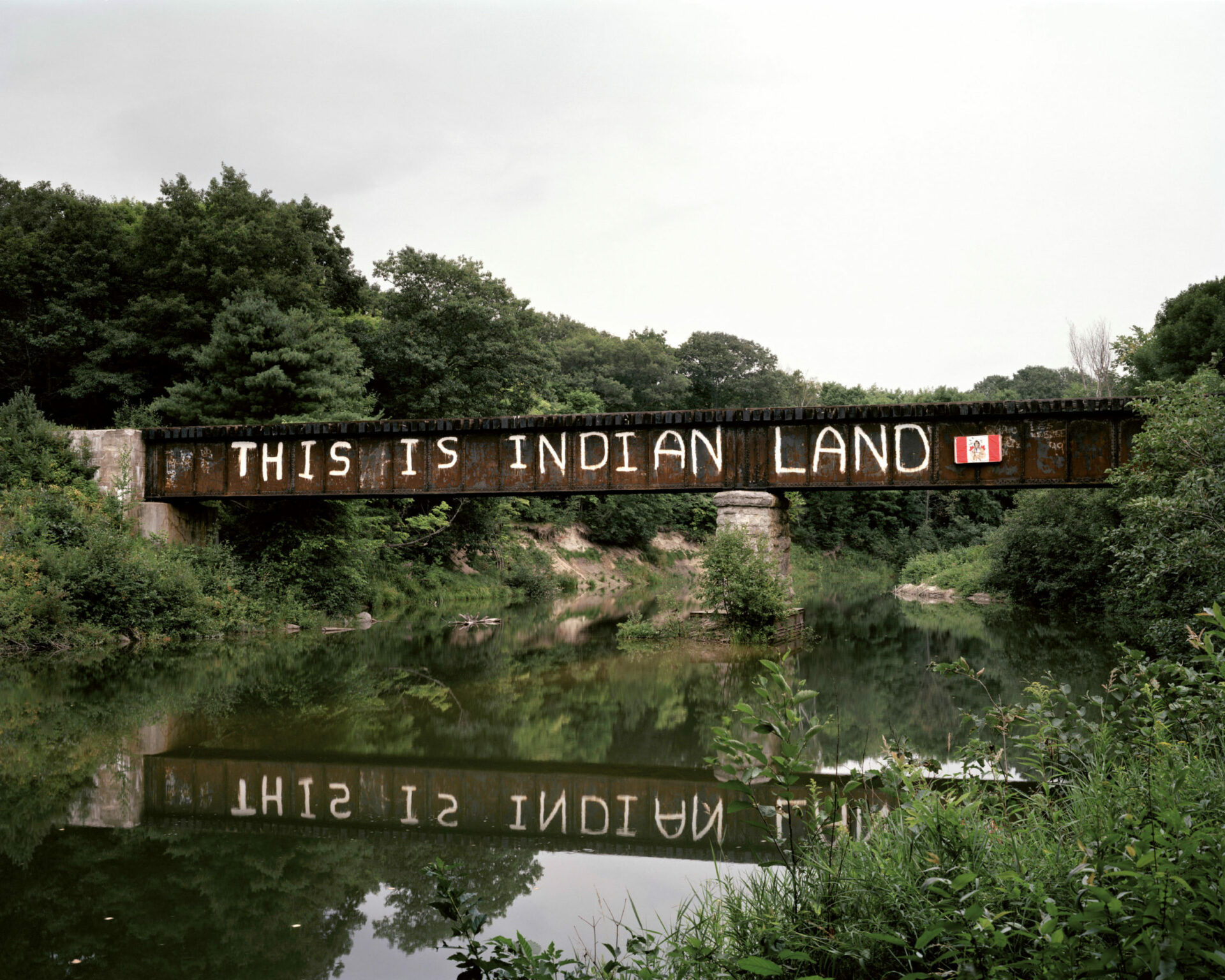

A Hypermodern Sublime

Defined by excess and the boundless, our period is that of the infinite, immaterial and instantaneous. Furthermore, our everyday space now appears to be endowed with a “virtual halo”1 1 - Louise Poissant, “Colonies et paysages dans le cyberespace,” Revue d’esthétique, no. 39 (2001): 49-55. of interwoven digital circuits and invisible waves which have done away with the notions of distance and time as we understood them less than twenty years ago. Regardless of whether they call it hypermodernity, supermodernity or liquid modernity, anthropologists, sociologists and philosophers are in agreement: the network age has brought about a completely different relationship to time, space, and to oneself and the other. So much so, in fact, that they see this as a real anthropological mutation2 2 - See Marc Augé (that is to the ensemble of his work since Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity 1995 [1992]), Nicole Aubert (L’Individu hypermoderne, 2004) and Zygmunt Bauman (Liquid Life, 2005). Nicole Aubert characterizes:the type of individual we have apparently become as hypermodern.3 3 - Nicole Aubert, L’Individu hypermoderne (Ramonville St-Agne: Érès, 2004). This term is used for its direct reference to excess, the boundless and the extreme.

The world has always escaped our bounds. And since the beginning of time, it has also been a source of the sublime.However, in a hypermodern era this “pleasure mixed with dread”4 4 - Emmanuel Kant, Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime (Irvine: University of California Press, 1960). seems to take on an entirely new form: after the sublime of nature, we have entered the technological sublime. In fact, for Mario Costa,5 5 - Mario Costa, “Paysages du sublime,” Revue d’esthétique, no. 39 (2001): 125-33. the subject is no longer only submerged in the immensity of the real, but also in the immaterial infinity of the network, in a non-landscape of the too-full, of too big and too numerous possibilities. “Like an insatiable bulimia of the gaze,” Costa states, “I can observe and digest the visual translation of the entire universe by allowing myself in a certain way to be absorbed and dissolved in it.”6 6 - Ibid., 129. Today’s world, already ungraspable in its entirety for its inhabitant’s mind, is doubled; and its second form (layer) is all the more difficult to objectify because of its immaterial and invisible nature.

photo : Robert Skinner

Scale Inversion in Contemporary Art

At the same time, we are witnessing a re-materialization of the work and a return to its physical existence. Actually, in parallel to relational, conceptual and immaterial works, which continue to inhabit our artistic landscape, for several years there has been an observable return of the tangible “handmade” work. In the wake of this renewed interest in the object, scale model works and their miniature mises-en-scène abound, thus providing the viewer with a very singular viewing opportunity, both in terms of scale and duration. While we are submerged in the infinitely big and the immateriality of the virtual, and accustomed to the rush and immediacy of networked communication, many contemporary artists are working on microcosms that divert the norms of hypermodernity, and thereby bring us back to a scale that is not only thinkable, but also controllable. These artistic practices emerge as an inversion of the new relationships to the body, time and space that define us nowadays. In the face of works resulting from these practices, the viewer has the impression of reigning both as master and guardian over a world that, in its everyday form, escapes him or her and remains excessively beyond reach.

It is this impression that Karine Giboulo’s miniature worlds instil in viewers. Her human-sized manufacturing complexes (All You Can Eat),7 7 - Created after an infiltration of factories in Shenzen and presented at the Galerie [sas] in the spring of 2009. housing hundreds of Chinese workers, call upon the viewer to bend over the windows to discover about thirty scenes of their daily life, usually hidden behind the walls of these cement behemoths. We thus become a colossal voyeur who is privy to the reverse side of our Western reality. We are invited to explore a factory that produces ribs and wings, which are not made of chicken, but of flying pigs that the workers feed with Miracle Grow before sending them off to the slaughterhouse. Further on, a hundred or so men and women in blue uniforms identical to the colour of the building, fill workrooms. On the roof of the dormitory and illuminated by the neon light displaying the Wing’s Day of the adjoining restaurant, a couple, still wearing the blue uniforms, is joined in a kiss. From one window to the next the work unfolds like a 3D comic strip in which the viewer’s presence — as a consumer of Made in China commodities — is implicit. The viewer’s position as a giant towering over the scene, which evokes the relatively hidden side of his or her everyday life, at times becomes quite uncomfortable.

If All You Can Eat represents only a fragment of the city, Village Démocratie (Phase 1)8 8 - This work, which was exhibited in June 2010 at the Galerie du Nouvel-Ontario, is the first part of a vast work in progress. is for its part a scale model of an entire megalopolis. Actually it is a concentrate of the planet and its social systems, a model of a vast “global village” where diametrically opposed realities are placed alongside one another. Echoing the extravaganzas of Dubai, there is a sparkling skyscraper displaying stock market indicators, on the roof of which business suit-clad golfers play; a building that is not only surrounded, but traversed by a gaping expanse of shanty towns grabbing every parcel of available land in an almost palpable expansion movement. Between the logos of big capitalist corporations the shanty towns infiltrate the territory and dig in. Between the advertising clips displayed on high definition screens on the gleaming façades of the ultramodern towers, the viewer can make out the reflection of other shanty towns arising at a distance. Thus reproduced in all its excess, the megalopolis can be observed down to the minutest detail. Bending over it in a posture alternating between domination and protection, and faced with the gravity of the themes presented (just as in All You Can Eat), the viewer cannot help but feel a certain unease. Beyond the reflections it leads to (and these are numerous), the model which the viewer observes from a suddenly so imposing upright body position, inverts one’s customary posture and hence exacerbates the sensation and consciousness of one’s body in the space.

photo : Robert Skinner

In a world that seems to be liquefying, i.e. to borrow Ollivier Dyens’ idea, a world in which the only remaining routine is ironically that of change, of replacement, and the perpetually new, Giboulo proposes micro-universes grounded in matter, at a scale which makes them (finally) graspable. Before this new and radical precariousness which has overtaken notions of continuity, stability and solidity, before that which we have called the hypermodern sublime, can the experience proposed by such models not be said to provide a certain feeling of mastery over the world and its new infinite named the “digital”?

Partaking in Duration

In partaking in duration, both in the work’s creation and reception, and in countering the current logic of urgency to do more in less time, can’t practices such as Giboulo’s be seen to provide a modality to master time, which today runs more than it flows? In imposing a pause, a brake, they refuse to play the game of haste and instantaneity demanded by our contemporary society. These are works that require slowness, as much in the “doing” as in the “seeing,” both of which are extended, and by way of innumerable details, involve precision, rigour, and even obsession. Giboulo’s worlds contain hundreds of minutely painted and sculpted characters. The more her projects evolve, the more the components are multiplied: All You Can Eat displayed some 300 figurines; Village Démocratie, will, upon completion of all its phases, contain twice as many. If there is excess here, it goes against the grain, for the obsession with the meticulous and the slow is substituted for the rapid and the instantaneous.

In the overload and density of the staging, the body is at once the master of the whole and the prisoner of the details. In this way Giboulo’s works — which give the word “colossal” an entirely different meaning — invite the viewer to a particularly meticulous gazing experience, one that is on par with that of the work. The time of “doing” thus joins up with the “time of seeing”9 9 - Terms borrowed from Edmond Couchot, “La dimension temporelle de l’image,” Des images, du temps, des machines dans les arts et la communication (Nîmes: Jacqueline Chambon, 2007), 19-56. in a mode which could not be more opposite to the hypermodern temporality such as we have defined it.

A Romantic Renewal?

The “tragedies of landscape”10 10 - David d’Angers cited in Michèle Grandin, “Friedrich, Caspar David,” Encyclopaedia Universalis. At: www.universalis.fr/encyclopedie/caspar-david-friedrich/. Accessed on March 28, 2010. of nineteenth-century Romantic painting are associated with the sublime in nature, and these paintings proceed precisely by inverting the posture of the human being in the face of nature.Standing before Giboulo’s microcosms, therefore, isn’t the contemporary viewer the hypermodern figure of Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog,11 11 - Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, Caspar David Friedrich, around 1818, oil on canvas, 95 x 75 cm, Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany. or some new incarnation of the Romantic man as he was presented by German painters of that time? Having stepped out of the painting, he now towers over — physically and not just by means of projection — the object of a new sublime. Because through these miniatures, it is not only the gaze but the entire body that takes in a vast and dizzying landscape, rendered here on a scale that makes us powerful, and it fragile.

[Translated from the French by Bernard Schütze]