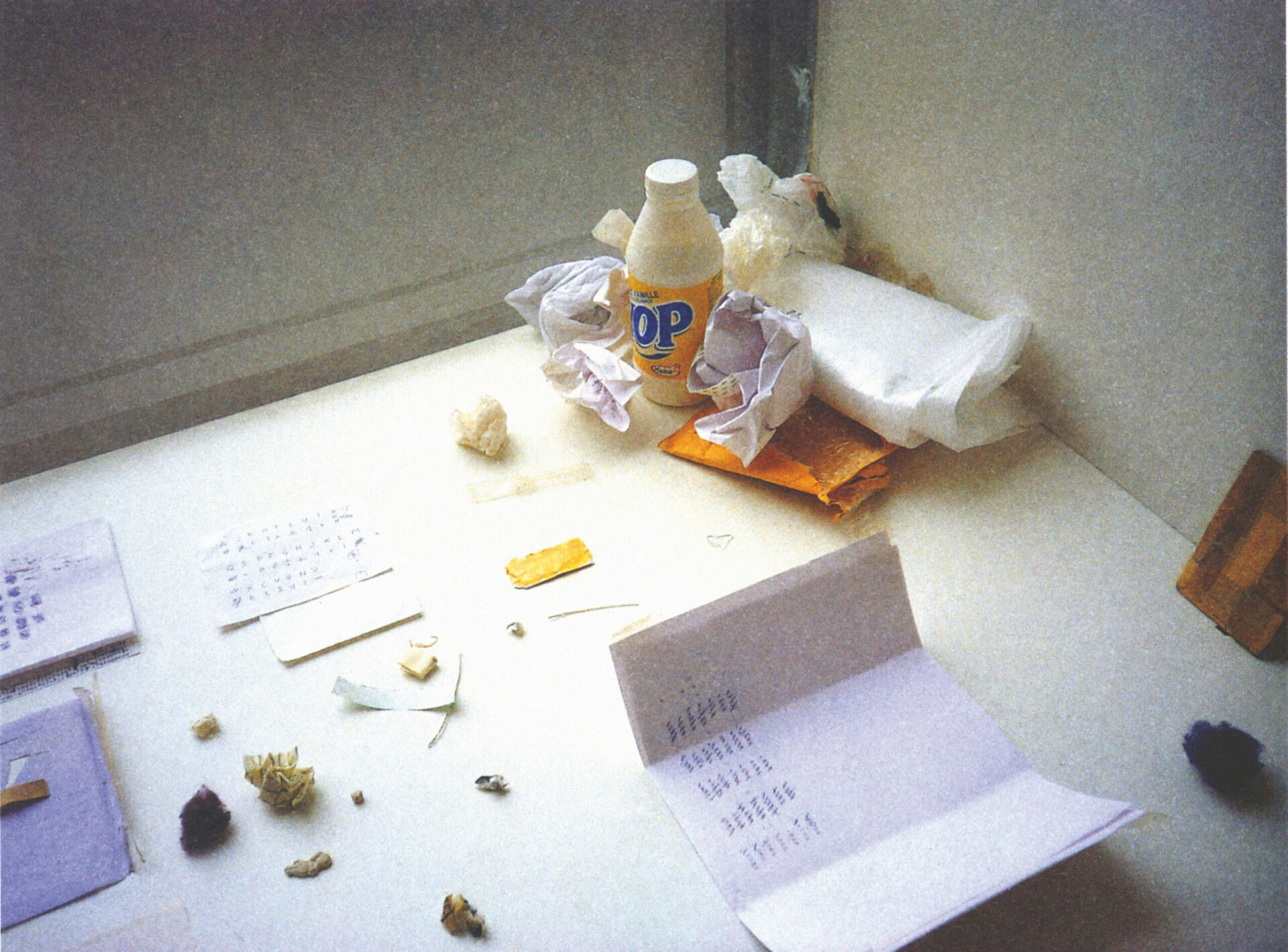

Photo: Bruno Sinder

Littoral Entanglements: The Fractured Lives of Plastic Artworks

As seasons pass, these strange relatives of the tumbleweed continue accumulating material, becoming more densely and tightly packed. Eerily beautiful in their materiality, unsettling in their showcasing of nature-human-industry relationships, the clusters might be considered art-adjacent, and because of this they give us matter with which to think through the materiality and evolving lives of artworks, including those made from plastic and those that combine natural and anthropogenic materials. Discussing the intensive labour required to keep artworks in the Museum of Modern Art from appearing to alter and change over time, scholar Fernando Domínguez Rubio suggests that “a museum is not a collection of objects but a collection of slowly unfolding disasters.”2 2 - Fernando Domínguez Rubio, Still Life: Ecologies of the Modern Imagination at the Art Museum (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020), 6. Indeed, it is becoming increasingly evident that artworks, even those stored in the most carefully controlled environments, are what he calls “tentative realities,” each of which should be seen as “a slow event that is still taking place as it unfolds through organic and inorganic processes.”3 3 - Rubio, Still Life, 2–4. On the shoreline of Lake Huron, the effects of the elements on the art-like Neptune balls speed these processes to a visible cadence, prompting the question, What is the time of plastic art?