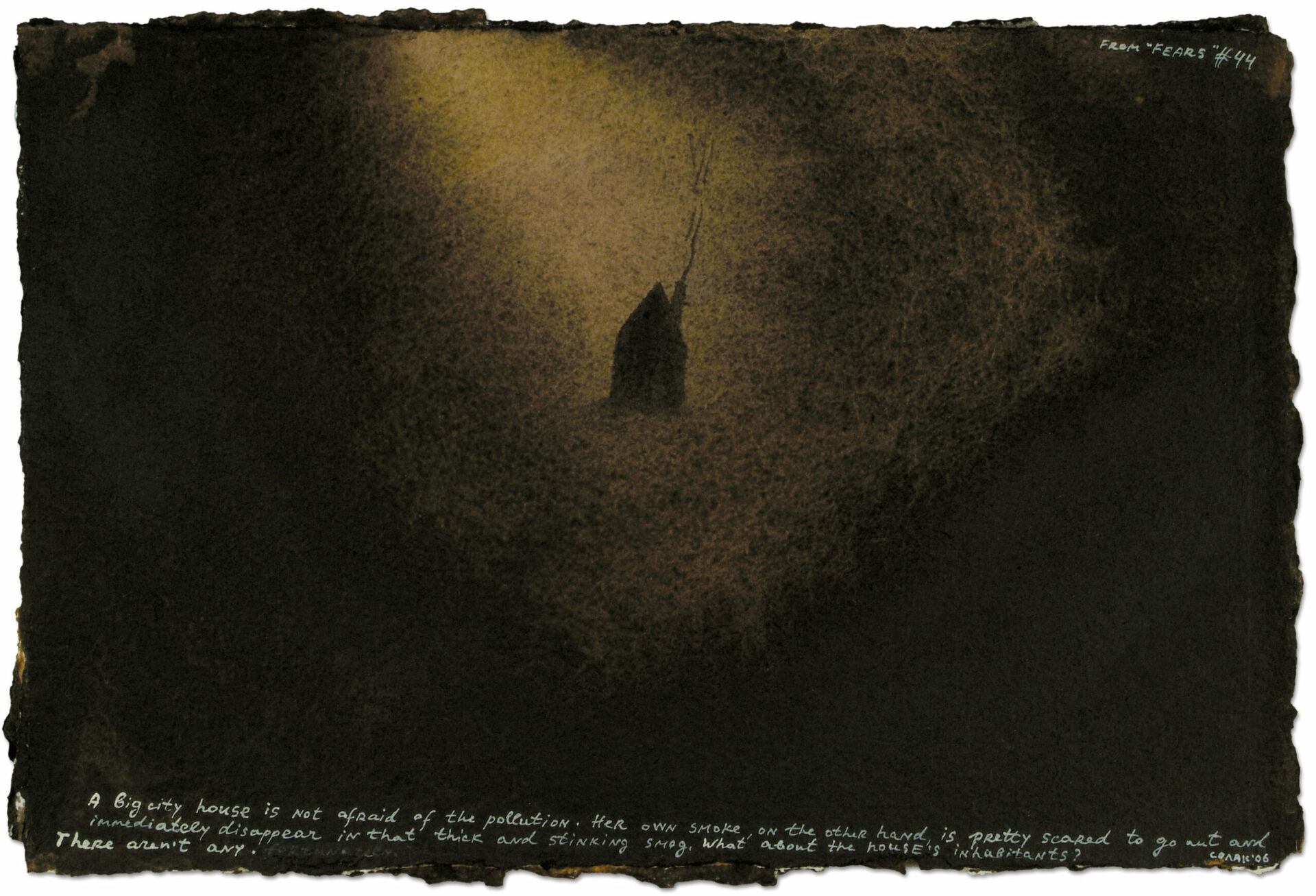

Photo : © Harun Farocki

With Open Eyes: Affective Translation in Contemporary Art

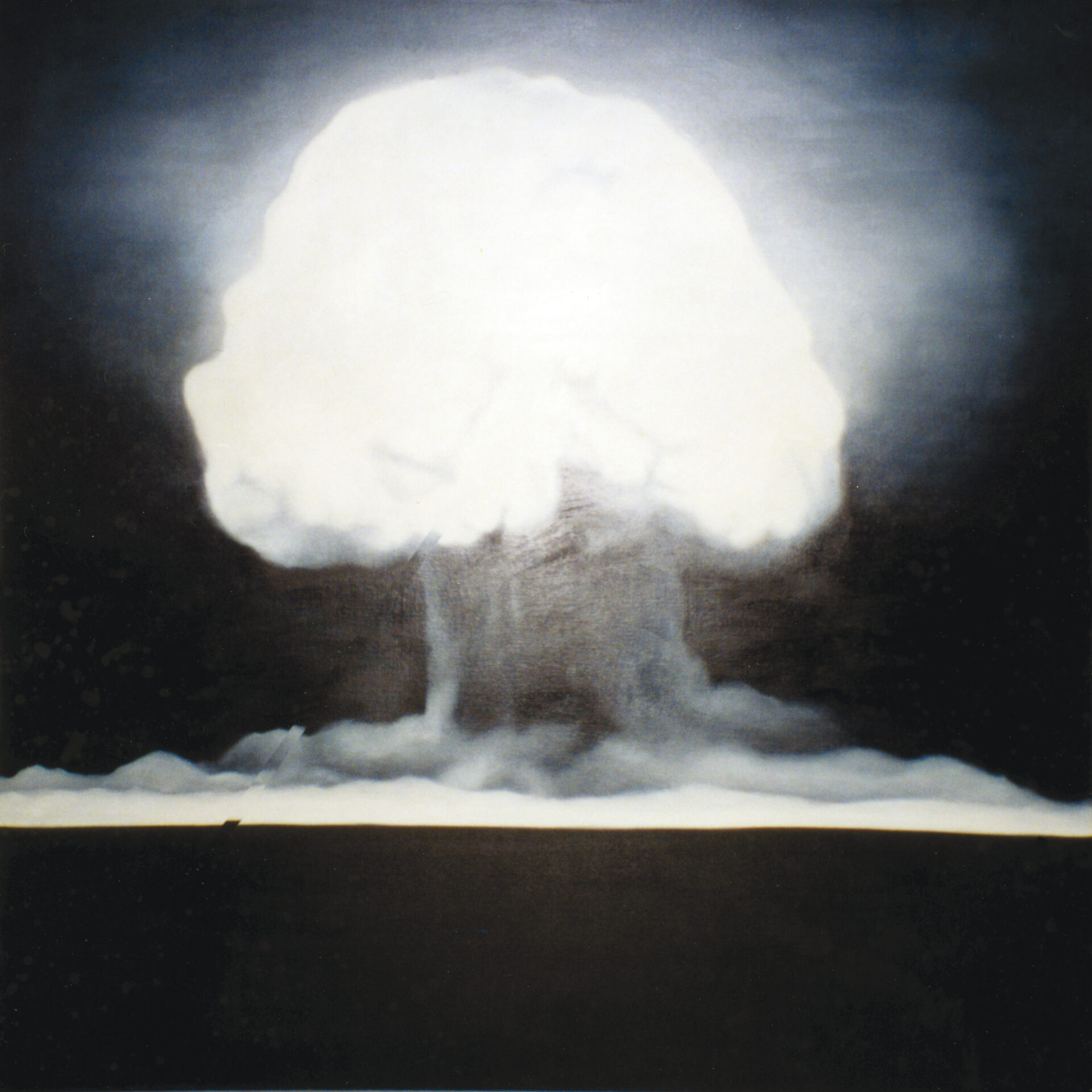

Reaching his hand out of and then back into the frame, Farocki holds a lit cigarette. As the camera zooms in on his forearm we are told, “A cigarette burns at 400 degrees. Napalm burns at 3,000 degrees,” and with this, Farocki pushes the burning embers into his skin. A kind of pseudo-documentary follows this scene: scientists and workers are shown in a simulated version of the Dow Chemical Company, which was responsible for producing napalm. The camera exposes offices, secretaries, chalk boards, and lab coats. But a visceral close-up of a charred wound interrupts this narration, persistently, as if recalling the haunting memory that Farocki warned us of. With each eruption of the image, the cringing worsens: first, the blackened wound of the skin exposed to napalm, or to the cigarette — this is kept quite ambiguous — is rubbed by an intrusive finger. In the next image flash, silver tweezers prod the wound. In the final escalation, the tweezers peel off flesh. In utilizing both this assault on embodied perception via the wound and the estranged contextual thread, Farocki employed devices that can be linked to discussions of empathy and emotional identification with artworks, as did Bertolt Brecht, Roland Barthes, and, more recently, Jill Bennett.1 1 - “Embodied perception” signifies how our bodies are themselves vessels for perception, engaging with others’ movements, expressions, or, here, injuries through an automatic physiological act that then sparks thinking. Although some philosophers and neuroscientists have explored this term (it relates to mirror neuron theories), I refer to how Jill Bennett has used it in her discussion of empathy and art. See Jill Bennett, Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005). For a discussion of Farocki’s work and empathy, see Clio Nicastro, “Harun Farocki: empatia e conflitto,” Epekeina 7, no.1 — 2 (2016): 1 — 9. He also posed the critical question of how artists can evoke empathy in a way that neither compels spectators to close their eyes nor permits them to gloss over their (in)direct culpability by seamlessly projecting their pain as the pain of Others, the suffering of anything outside the perceiving subject but, most particularly, of oppressed peoples within colonial histories. Farocki’s attention to devices of empathetic spectatorship — here, the narrative and the wound — continues in two recent works of Candice Breitz and Berlinde De Bruyckere that highlight the politics of affectively connecting with Others.