Dare to Dream

Although dreaming is not unique to human beings, our species has always paid particular attention to the experience of dreams, even to the point of being obsessive. From the ancient beliefs of divination or oneiromancy, which endowed dreams with prophetic meaning (the dream turned towards the future), to the psychoanalytic approach of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung (the dream turned towards the past), dreams have been used as powerful tools of self-knowledge or world-control. In the call for papers for this issue, the editorial committee asked the following question: “Does the interpretation of dreams kill their ability to affect life?” Drawn from a Weird Studies podcast, in which writer J.F. Martel and musicologist Phil Ford discuss The Dream and the Underworld by psychologist James Hillman, the question is intriguing.

In his book, Hillman writes: “A dream compared with a mystery suggests that the dream is effective as long as it remains alive. … This implies to me that dreams can be killed by interpreters, so that the direct application of the dream as a message for the ego is probably less effective in actually changing consciousness and affecting life than is the dream still kept alive as an enigmatic image.1 1 - James Hillman, The Dream and the Underworld (New York: Harper Perennial, 1979), 122. We might wonder therefore if the will to analyze dreams by rationalizing them does not divest them of their multifaceted possibilities. This idea is addressed in our pages along with the suggestion that interpretation can be a violent act of extraction and a reminder that the rationalist Eurocentric perspective does not take into account the social and cultural specificity of dreams (for example, the holistic character of Indigenous epistemology). Maintaining their mystery might be a more interesting avenue to consider.

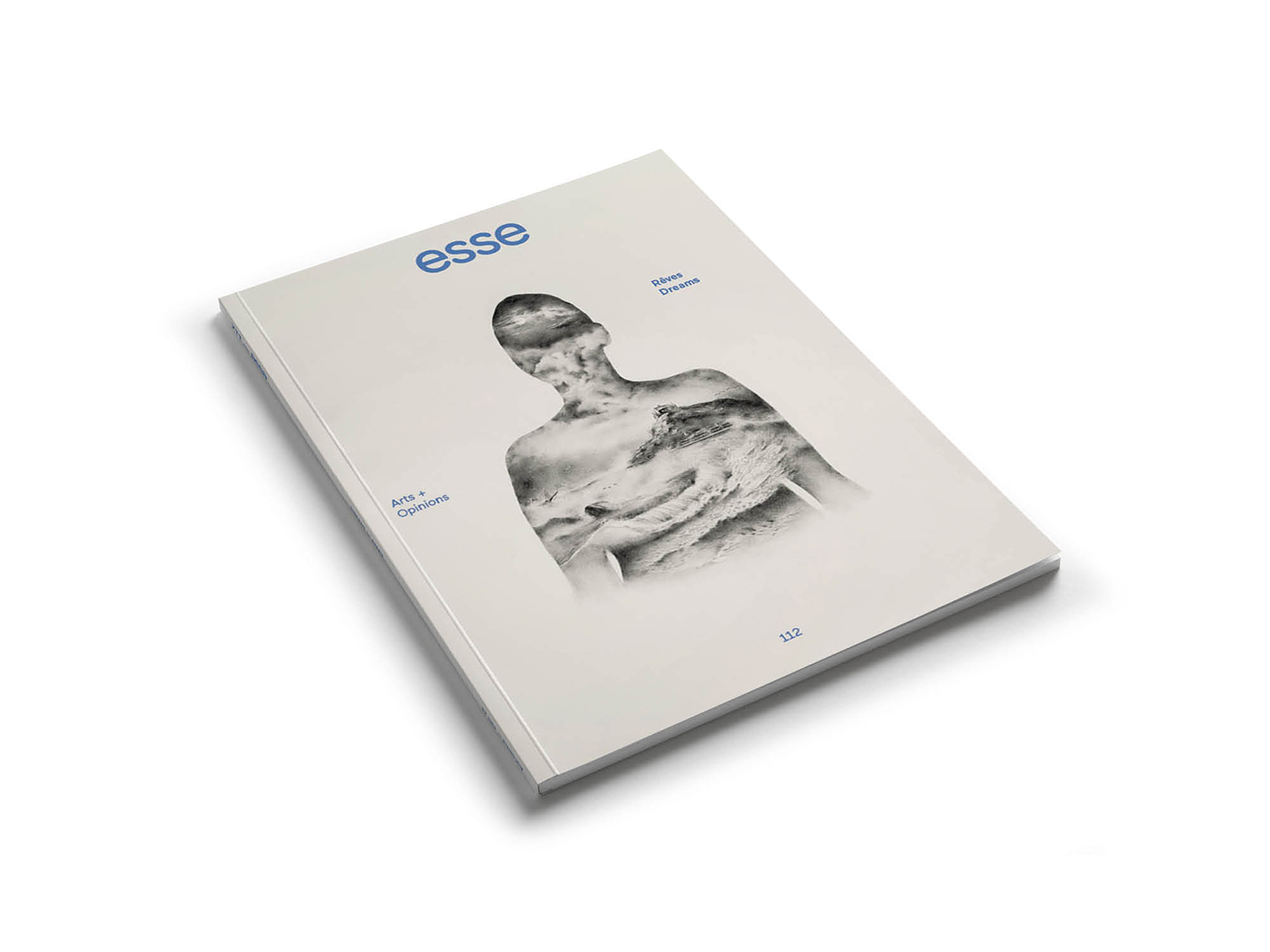

In the hands of artists, dreams become particularly rich materials to explore, especially since their connection to art is profound: the significance of mystery and ambivalence, the desire to resist interpretation, the ability to imagine reality in other ways. The feature section reflects on everything that defines dreams, from the mental activity that happens during sleep to the manifestation of desires or aspirations that transpires when awake, including the capacity of dreamers to represent other worlds. The realm of dreams brings together phantasmagorical fictions and absurd tales, dialogues between the conscious and the unconscious mind, geographies inhabited by the strong opacity of dreams, and numerous metaphors of hope and resilience. This certainly leads us to think of the dream, as in Ursula K. Le Guin’s novels, as a starting point for collective action or rebellion. A decolonial dream.

Prophetic dreams do not have a scientific basis, but the desire to make them into tools for imagining and transforming the future, by opening up new temporalities, is not meaningless. We propose to comment on the present and the past precisely by turning towards the future, appealing to the restorative nature of dreams, their vital force and agency, and recognizing their revolutionary potential.

Considering dreams also leads us to people who are more or less deprived of them, either because insomnia prevents them from experiencing dreams or because trauma or the violence of political reality — conflicts, dispossession, displacement — make their dreams “undreamable.” In this context, art once again becomes a special space for grasping and reinventing dreams. In their articles and works, the writers and artists invite us to open the portal of dreams and allow them to spread into our waking lives, to escape the reductionism of normative thought, to rebuild our collective imagination, and to make room for re-enchantment in the world.

Yet the world in which we live is getting gradually darker and at times seems to merge with our worst nightmares. As environmental disasters are becoming more frequent, we are being politically assailed by the hate of right-wing hardliners and the conspiracy-driven discourse of populists, in addition to all the hopeless conflicts. Never has the reconstruction of our dreams been more essential to maintaining hope for a luminous future. Fortunately, we are seeing actual forms of individual and collective resistance at a geopolitical level, which are attempts to restore some light to the world. More than ever before, we must dare to dream.

Translated from the French by Oana Avasilichioaei