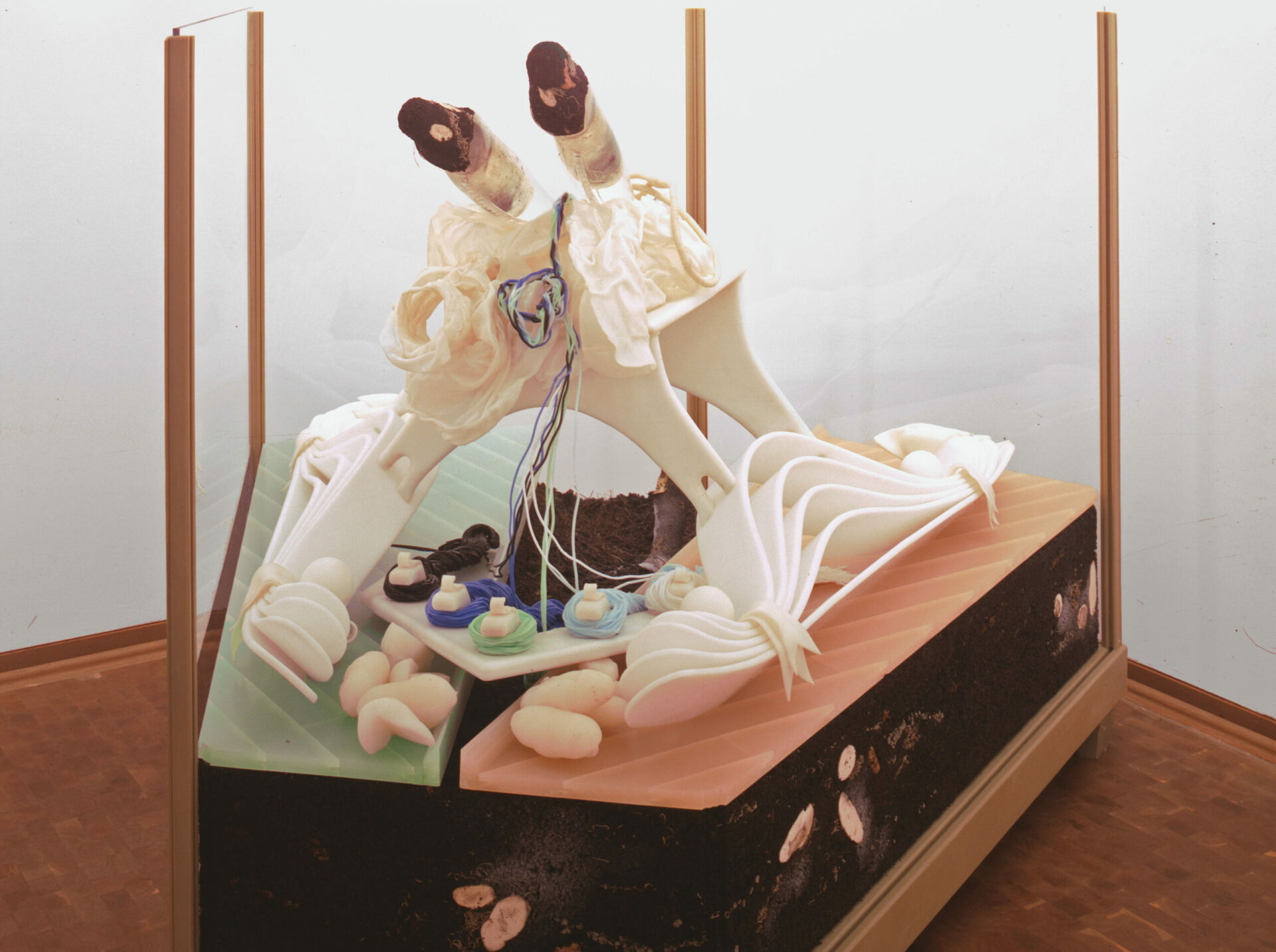

photo : permission | courtesy Galerie Claudine Papillon

Ten or twenty years ago, a major event took place that touched us all, inescapably. In an isolated region of Iceland, a small house disappeared, a victim of the elements, and, whether we knew it or not, we all vanished along with it.

What do we know about this smaller-than-average house, of which only a few black and white photos remain? Artist Hreinn Friðfinnsson (born 1943) built it in the summer of 1974, in the Reykjanes, a volcanic peninsula of the island where he grew up. We also know that Project House, as it was called, seemingly placed in the middle of a volcanic depression, helped materialize a literary fiction. Drawing on Thorbergur Thordarson’s novel Íslenskur aðall (1938), Friðfinnsson built the house along the same lines as the one constructed by the novel’s fantastical Solon Gudmunnsson, who wished that his house be inverted, that is, that the decorations (curtains, wallpaper, etc.) be displayed on the outside of the house, not the inside, so that all might benefit. Friðfinnsson thus created an empty, floorless house, its outside walls covered in wallpaper and punctuated with photos of its construction. In his strange house, neither home nor place of comfort, the exterior became the interior, though an interior now scattered outside its own walls.

photo : permission | courtesy Galerie Claudine Papillon

As opposed to Gudmunnson’s wishes, however, few could see this house. The artist informed no one about its exact location, did not encourage those interested in seeking it out, and made no effort to preserve and repair it over the years. Indeed, if one considers that the dwelling’s interior is outside it and that the exterior is therefore wholly contained within—as Friðfinnsson puts it, “this house contains the entire world, except itself”1 1 - Cited in Hreinn Friðfinnsson (Bignan: Centre d’art contemporain de Kerguéhennec, 2002), 80 (our translation). Exhibition held April 7 to June 2, 2002.—, one had no reason to visit the small house, for we were all already inside when Friðfinnsson built it. Following this reasoning, one may think that visiting this house, entering it, would be to step out of the world, to place oneself in an indeterminate space, a sort of vortex, a non-space.

Hreinn Friðfinnsson spoke of the genesis of this work in an interview with Hans-Ulrich Obrist.2 2 - Hreinn Friðfinnsson (London, UK: Serpentine Gallery/Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König/Listasafn Reykjavíkur Reykjavik Art Museum, 2007). Exhibition held July 17 to September 2, 2007). For Friðfinnsson, it was truly neither a sculpture that one might come to admire, nor an installation, and by no means a duly labelled and presented artwork. It was meant, in fact, to propagate in people’s minds, like a rumour or a secret. This point is particularly crucial in understanding the work, for such a foundation can be as firm as it is fragile: rumours can sometimes be more resilient than any other type of account. The work, then, was not meant for the would-be connoisseur who’d embark on the pilgrimage to Iceland, but for idle strollers who, having likely lost their way in this forbidding terrain, would discover and talk about it, until the gossip finally reached the artist’s own ears.

Besides these few strollers, Friðfinnsson’s little house existed only in the imaginations of those who might have heard about it, thus becoming part of an invisible community of individuals who knew of its existence but hadn’t necessarily seen it. To speak of community is quite misleading, however, since the latter was naturally aware of the fact that it would disappear one day, along with the house, when being together within it would no longer make sense—like the proverbial question about the noise the tree makes when it crashes in the woods with no one to hear it. One may even wonder if, knowing the house is now gone,3 3 - In his interview with Hans-Ulrich Obrist, the artist explains that the work had deteriorated in the previous ten years and that it was now little more than rubble. Ibid., 52. we can only mourn the passing of the fictional community that arose upon learning of it. One may do well to recall that the work demands of the invisible spectator a certain belief in this story, which doesn’t resemble a lie so much as a tale.

Fonds national d’art contemporain, 2007.

photos : Aurore Macario, permission | courtesy Domaine de Kerguéhennec

Friðfinnsson also engaged the memory of his own work, deciding to produce another little house. Second House—not Project House’s twin, but its not-so-distant cousin—was produced in 2007, for the Domaine de Kerguéhennec (Bignan, France), and while it too was a diminutive dwelling, its wallpaper and photos were properly laid and hung in its well-floored interior. One could also see, placed on an Icelandic rock and reflected in a mirror placed on the ground, a wire-frame remembrance of Project House. This work within the work reminds us that we were once in a little house very similar to Second House.

Seemingly lost on the Kerguéhennec grounds, just in front of the castle, this house awakens a childlike curiosity in visitors, who try to figure out what might be hiding within. Overlooking the pond, the work misleads us from afar; seeming other than it is—a little house—, it distorts the landscape, now becoming a fairytale setting, with huge trees and a house lost in the middle of the clearing. Only on approaching does the feint appear for what it is. We crouch to look inside. With its windows and doorway closed, we can only see within by wiping the grey, dust-laden window panes with our sleeves. However, as the house remains closed, it can’t help remind us of the vanished work of 1974, constructed as a legend we’d like to believe in.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]