photo : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

Relationships to the work’s locus and time have become aesthetic constituents of its expanded form. Such has been the case since the acceptance of installations, site-specific or not, as an artistic genre, since the appearance of land art, earth works and performance, the proliferation both of furtive and “process-oriented practices that take place over a period of time and that have to do with exchange,”1 1 - Patrice Loubier, L’indécidable / The Undecidable, trans. Mark Hefferman (Montreal: Les éditions esse, 2008), 195. and of manœuvres and other temporary interventions in public space. The artwork you see on display, whether in gallery spaces or outside of art venues, will not last. Or it is already over, experienced only through writing, photography, sound recordings, video, and websites. Art as stationary, permanent and stable form now seems archaic when compared with the complex, multidisciplinary projects that proceed by occurrences and infiltrate different layers of reality. Interest in impermanence, in ephemeral art is now ubiquitous. Not surprising, then, that the deterioration of objects becomes the focus of artistic process. The notion of fragility therefore goes hand-in-hand with that of durability. Fragile things are brittle, they threaten to break, crumble, lose consistency of form. Of course, the word “fragile” is widely used—for individuals’ lack of psychological and moral resistance, for human relationships, for the nature of appearances and representations, etc.—, but it is essential that we conceive of it here in its literal sense, not dodge the obvious—fragility is a material characteristic.

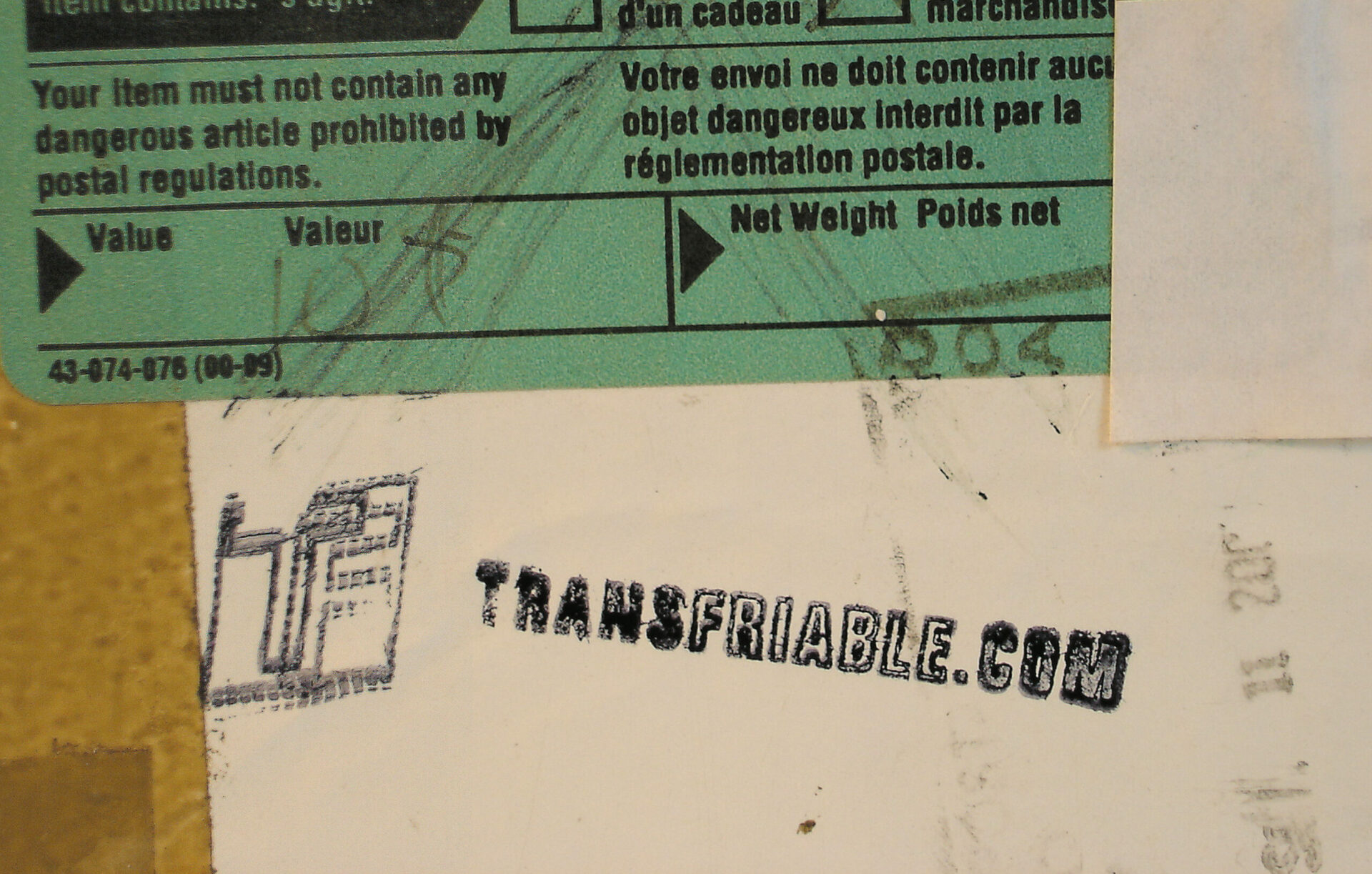

Patrick Beaulieu’s work offers a grounded point of reference for reflecting on this notion of fragility. Whether taking the form of installations of natural elements—branches, feathers, or butterfly wings, set in motion by luminous, mechanical, or electronic devices—, of a road trip down the long migratory path of the Monarchs,2 2 - Vector Monarca, a mobile multimedia project by Patrick Beaulieu, spanned over several months. Driving a small truck that could be transformed first into a video screen, then into an exhibition space, Beaulieu and writer Daniel Canty followed the migration of the Monarch butterflies from Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, Quebec, to Morelia, Mexico, where these mythic butterflies reproduce (www.vectormonarca.com). or of the creation of a package delivery company, his pieces, stemming from the brouhaha and uncertainty of trial and error and imbued with the poetry and subtlety of complex thought, are defined, again and again, by the very fragility of their materials. An artist whose tentacular creative projects branch out, extend and respond to one another through time and space, going from one venue to the next and proceeding by discrete occurrence, Beaulieu is particularly interested in the movement of animals, people, and goods, and in various tangential themes: borders, economics, politics, communications, deterioration, integrity, among others.

Transfriable is the artist’s neologistic designation for the springboard from which he and partner-workers have shipped and delivered fragile goods since 2003. Opening “branches” in exhibition halls, this “company” mimics and distorts package delivery companies’ discourse guaranteeing safe shipping and quick services: “Thanks to technical innovations in product resilience (which are redefining messenger standards), our employees focus on the composition of goods to determine the most appropriate effect. . . . The longer the delivery process, the better the package’s quality at delivery.”3 3 -

Dominiq Vincent, author of and partner in the company’s website: www.

transfriable.com.

Transfriable was first presented at the Observatorio Centro Experimental in Morelia, Mexico. In the exhibit space, we see a floor covered with bubble wrap, a desk, the company’s logo and its website on a computer screen, clocks showing the time in a few big cities, packing products, and two dozen cardboard boxes from Canada, containing bolts and broken crystal ware. The inclusion of bolts, not following packing procedures (neglecting to bubble wrap the objects or to use other shock-absorbent packing materials), and over-packing the boxes are sure ways to increase the risks of damage. By increasing the “factors of difficulty,” the system for protecting the object actually becomes the means for its destruction, thus overturning functional parameters.

photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

In tandem with the corporate staging in the exhibition hall, there were interactions with groups of people and actions undertaken by participating accomplices. The artist called on the skills of women potters from the village of Capula, asking them to make clay cups, plates and glasses, which were left unfired to increase their fragility. Videos on the company website show how it stumps expectations for shipping goods and the importance of safe handling: we see students standing in a circle around a fountain throwing boxes to one another, dropping them nonchalantly and laughing as if they were balloons; we also see a delivery person, arms loaded with packages, stumbling through a square, dropping his apparently fragile load, the din attracting the attention of a few passersby who kindly offer their help.

Though such manœuvres seem to target two audiences—witnesses unaware of the deception and the forewarned who will see the work’s various mediations—, this twofold target is not exclusive. Everything depends on the artist’s desire to reveal his trickery and the different audiences’ interpretation of the events’ reality. Video-watchers who think they see honest passersby hurrying to help a clumsy person are perhaps dupes to the accomplices’ game. Beaulieu blurs the line between true and false from within the very system he has established.

Two years after this first presentation of Transfriable, a second branch opened at the Hatch Art Center in Mexico City. Again, we see a desk, the company’s logo, the clocks, a computer, and packages of broken crystal from Canada. But this time, there are also boxes shipped from Morelia containing unfired clay pottery that has been shattered by bolts and nearly reduced to dust. While up to this point the content of the boxes had been destroyed by just one thing (the metal breaking the glass), now the clay’s humidity had also accelerated the oxidation of the hard matter, causing an unexpected effect and a reciprocal destruction of the materials. These packages of fragilized contents were then sent to Gand, Belgium, for the inauguration of a third branch at the Experimental Intermedia v.z.w., where they were put in a bay window looking out over the street. To the presentation of the company and the display of packages of broken Canadian and Mexican objects, the artist now added a shipping pallet loaded with 120 Belgian beer glasses and a video projection of package handling in Gand, where we see a tramway blocked by packages that have been dropped by a freight handler. The scope of this act extends beyond the individual to group infrastructures, as the accident it provokes disrupts the daily life of a well-ordered, efficiency-conscious community.

photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

The company’s last exhibit, called Transfriable – Lost Docks, was held in 2006 at Plastic Kinetic Worms in Singapore. Along with packages shipped from Canada, Mexico, and Belgium, the installation also displayed an aquarium of goldfish held down by black bungee cords on a loading pallet. Projected on the wall, a video played the different stages of the acquisition and shipping of this aquarium, which had been placed without protection in the middle of a shipping container. The container is therefore no longer a box thwarted from its basic function—protection—and containing other containers (pots, glasses, crystal ware); rather, it becomes the necessary condition for the fishes’ captivity. The container-aquarium offers up living contents, little beings at the mercy of human handlers and, to believe the video, their death appears imminent.4 4 - The results of this live expedition from Singapore will be shown at Clark’s, in Montreal, from May 7 to June 13, 2009. An ethical dimension—that of using animals in art—is thus added to the artist’s exploration of true and false, and the movement of people and goods.

By imitating companies’ solicitous strategies and discourse, Transfriable invites us to question their intentions and the nature of the needs they pretend to meet. Absurd and voluntarily “unproductive,” Beaulieu’s work turns the notion of profitability and efficiency on end and encourages us to rethink the values underlying our consumer society: the commercialized products’ lack of resistance, and the exploitation of workers. While Beaulieu’s company attempts to control factors in the deterioration of the fragile matter being shipped, the absurdity of the project’s aims and its content-container interplay are nonetheless reminiscent of Dadaism, questioning the idea of functionality and of our relationship to matter: “Inexhaustible, vertiginous, and bulimic, boxes can contain anything. It’s what one might call the ‘body without end,’ or the ‘infinite of the box,’ which refers back to a kind of dizzying quality in matter, of an unmastered and probably unmasterable diversity.”5 5 - Florence de Mèredieu, Histoire matérielle et immatérielle de l’art moderne (Paris: Larousse/Sejer, 2004) [first edition Bordas, 1994], 244. Indeed, this work becomes a celebration of the inefficient, of the unreasonable, and of the irrational. By taking part in the shipping services for fragile goods, the project also justifies a reflection on the considerable efforts deployed in safely shipping and conserving works of art, precious goods par excellence. As such, if we consider the instances of Transfriable as exhibited finalities, the boxed fragile goods come to represent real fragilities, crumbling out of doors in “real life,” where they are neither representations nor represented, their insignificant existence unnoticed. The artist creates a kind of paradoxical system that brings back to the world of art the absurdity of its phenomenological and conceptual isolation. But since the Transfriable exhibitions show the state of the objects after real travel, they are like passageways between past and future events, becoming signs of the company’s activity in the world.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]