Photo : courtesy of the artist

Neither Artist Nor Worker

In response to economic insecurity, there is of course a history of government and philanthropic support for culture. After the Depression and the Second World War, Western governments began to integrate the arts into the welfare state and to develop cultural policies based on the belief that culture should not be sacrificed to free market principles. Since the 1990s, however, the idea of protecting culture from market forces has been almost completely reversed, with creative industry policies now leading the way in the development of newmarkets.1 1 - See for example the speech by Mélanie Joly, Minister of Canadian Heritage, “Creative Industries: Exploiting the Potential of New Markets,” at the Montreal Council on Foreign Relations, April 17, 2017, <corim.qc.ca/en/event/762>, and <bit.ly/2IhLyys>. On the subject of creative industries policy, see Marc James Léger, “The Non-Productive Role of the Artist: The Creative Industries in Canada,” Third Text 24, no. 5 (September 2010): 557 — 70.

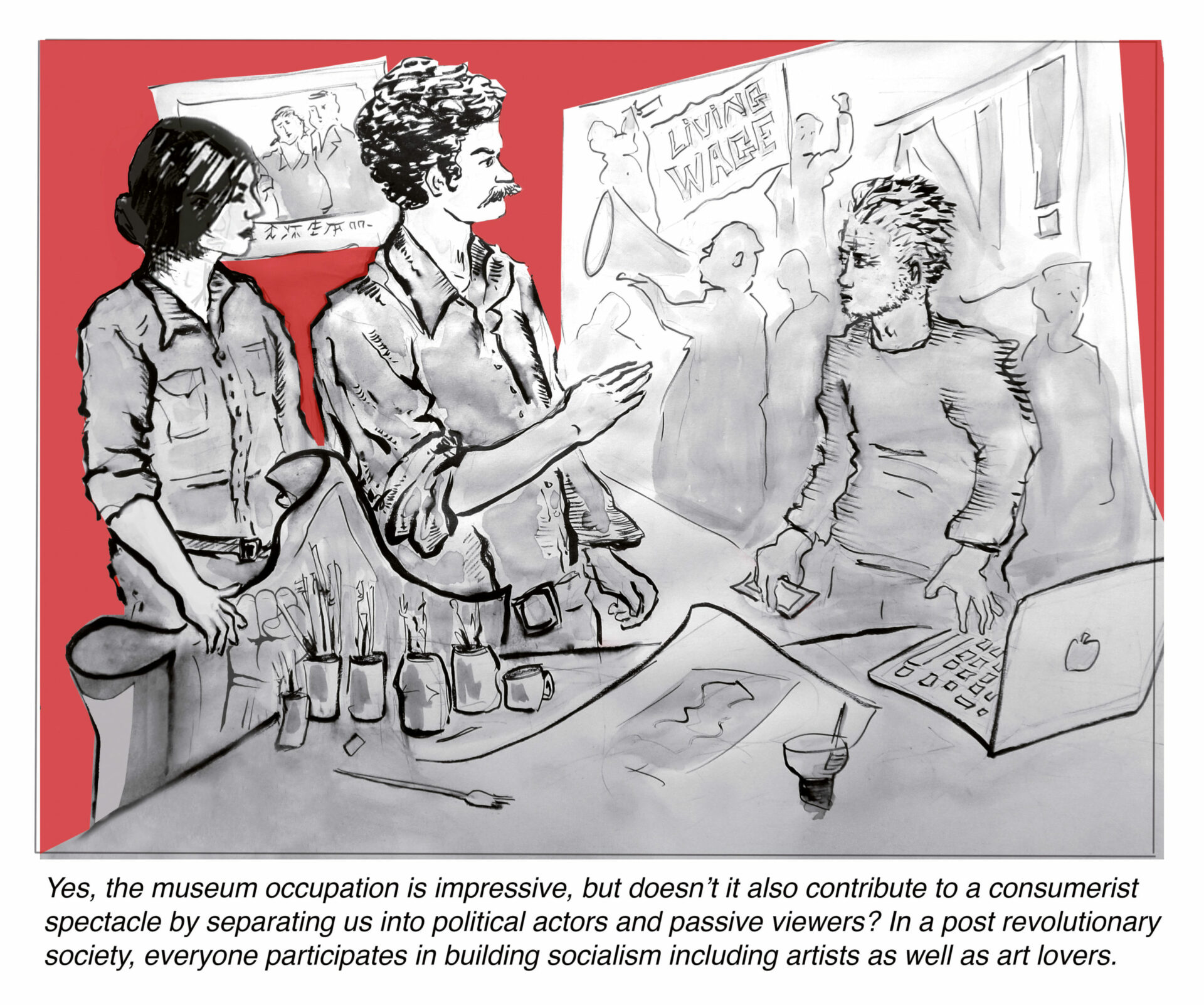

It’s Still Privileged Art (Homage to Condé & Beveridge), 2016.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Aside from experiments in socialist countries, the classic case in recent history is the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC), which, from 1969 to 1971: advocated for artists’ rights; demanded institutional inclusion, the unionization of museum staff, and an overhaul of the art press; worked to decommodify art production; and otherwise sought ways to have more economic and ideological control of their work. According to Julia Bryan-Wilson, despite its achievements, the AWC’s left-leaning and pro-union efforts to define artists as workers, and art as labour, failed to result in a collective identity, let alone a unified set of political concerns or similar approaches to makingart.2 2 - Julia Bryan-Wilson, Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam Era (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009).

Bryan-Wilson suggests that the term “art worker” is something of an oxymoron insofar as art-making is a non-utilitarian and non-productive activity that is defined by its difference from most other activities, including leisure pursuits. The non-productive status of art is usually attributed to Karl Marx’s writings in the Grundrisse (1857 — 61), Theories of Surplus Value (1862 — 63), and Capital (1867, 1885, 1894), in which he makes distinctions, for example, between a pianist and a maker of pianos, or between a writer and a book publisher. Whereas one makes art, the other produces commodities. Because of this division of labour, art has a greater potential to express the notion of non-alienated or free labour. The most cogent analysis of art as free labour in recent times is Dave Beech’s Art and Value (2015), which I will address here in somedetail.3 3 - Dave Beech, Art and Value: Art’s Economic Exceptionalism in Classical, Neoclassical and Marxist Economics (Leiden: Brill, 2015). Beech is a member of the FREEE Art Collective. See http://freee.org.uk. Among some of the researchers who have addressed the relation between art and economic value, see also the writings of Hans Abbing, Arjo Klamer, David Throsby, and Ruth Towse. While most cultural theorists in the tradition of Western Marxism and the Frankfurt School have been satisfied to draw on Marxist political economy, Beech’s book is unique in its examination of the way that art’s exceptionalism is also intrinsic to both classical liberal economics and neoclassical (neoliberal) economics. His theory, in essence, is that art is economically anomalous. Although he does not dispute the notion that art labour is affected by and incorporated into capitalism, he makes the case that there is little evidence to show that art-making coincides with capitalist commodity exchange.

Artists who have difficulty making a living, even in today’s bonanza of entrepreneurialism, also have a history of organizing around the notion that in a capitalist society, artists, like all other workers, are exploited.

Beech proposes that art has not fully made the transition from feudalism into capitalism and that it remains, like a cottage industry, in the mode of “simple” and not “capitalist” commodity production. The work of art dealers, collectors, and auctioneers tells us nothing about the production of art. As he puts it, “Art does not become economic by beingsold.” 4 4 - Beech, Art and Value, 24. Moreover, art’s exceptionalism is not the result of a heroic refusal to “sell out.” There are flaws with Beech’s analysis, least of all the fact that, from a social perspective, the existence of art’s status as simple production depends on a global division of labour that includes commodity production. As he acknowledges, art’s exceptionalism could be used as a means to get capitalism off thehook.5 5 - Ibid., 19. Regardless, according to Beech, the making of art is on a different order than its fate within capitalism. Artists, insofar as they can be defined as artists, control their means of production, even if they make use of capitalist processes and market mechanisms. Artists who make use of capitalist techniques create art that can only succumb to the “fetishist illusion” that it has taken on the enigmatic character of the commodity. The problem with this perception is that it presents a magical solution to a more difficult problem, which is that even if art is socially subsumed by capitalism, it has not been economically subsumed by capital. Cultural policies, therefore, especially policies that either seek to protect culture from market forces or argue for culture as a market force, should not rely on arguments that do not stand the test of economic analysis.

To wit, and according to classical liberal economists: unlike workers who produce value through commodity exchange, artists are frivolous and unproductive; artists produce profits for capitalists; artists can sell their work, but they do not sell their labour; the work of performers is consumed immediately; prices for artworks, some of which become expensive luxuries, are based on rarity and monopoly as a natural limitation of supply; such rare luxuries, usually attributed to the artist’s talent, cannot be consumed; one cannot base prices on the labour time required for the production of art, and labour cannot be added to its production, that is, according to a labour theory of value. In short, in classical economics, art prices and artistic labour do not conform to the laws of supply and demand. In neoclassical or neoliberal economics, the marginal utility of art is a form of exceptionalism; consumers impose their will on producers through demand but do not do so in the case of art; artists occupy the place of the consumer against market value; art production is irrational and risks poverty; or, art is a calculated risk that extends the cost of production. And in Marxist economics: workers’ economic self-interest is not an asset for workers but for capitalists; if capital circulation is the driving force of society, defined by Marx as Money-Commodity-Money, art continues to oper-ate in terms of Commodity-Money-Commodity; art prices and the utility of art to consumers do not allow us to distinguish between products that are or are not produced according to a capitalist mode of production; because art is not produced as a commodity, the classical labour theory of value does not apply and the artist is not exploited like other workers.

Despite all this, and beyond the function of art in class society, Beech argues that the best way to determine whether or not art has been colonized by capitalism is to examine the transformation of labour in post-Fordist societies, in which services, including cultural services, are increasingly indexed to market measures and performance indicators, changing artists into productive capitalists. According to Beech, the only way to salvage art in the context of global capitalism is to make it part of a cultural and intellectual commons that is free from bureaucratic and economic control. Meanwhile, artists have found new ways since the AWC to build common and collective identities against capitalism. Gregory Sholette, for example, addresses the ways in which artists have sought to “exit” the art world’s celebrity showcase and critique its political economy. Such artists, he argues, increasingly see themselves as a category in itself and for itself — a realization that is enhanced by capitalist communicationnetworks.6 6 - Gregory Sholette, Delirium and Resistance: Activist Art and the Rise of Capitalism, ed. Kim Charnley (London: Pluto Press, 2017), 214.

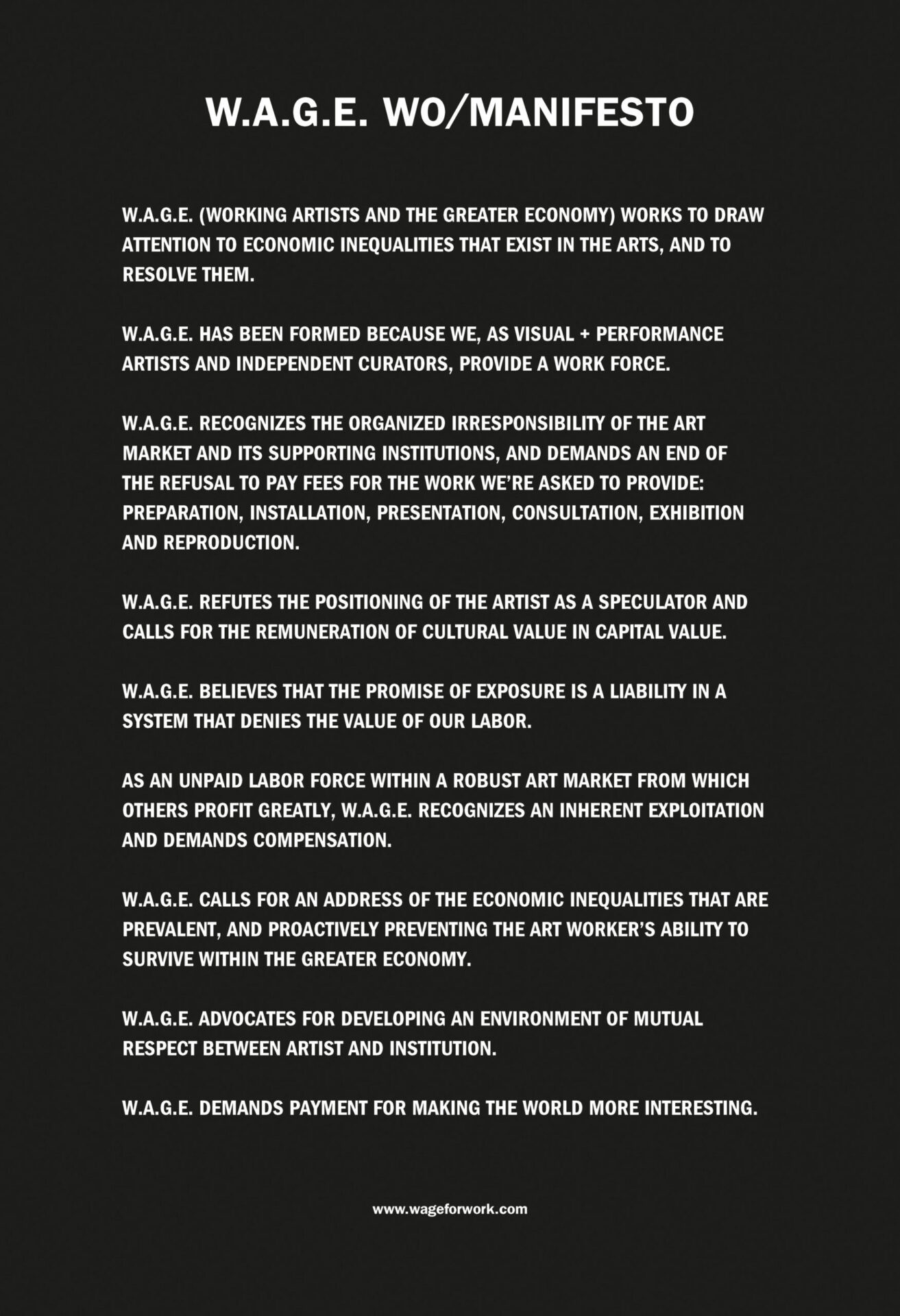

Different forms of “escapology,” as Sholette calls them, can be found in the work of W.A.G.E., BFAMFAPhD, and Arts & Labor — groups that understand their activity, oddly enough, as a source of value. Inspired in part by the CARFAC (Canadian Artists’ Representation / Le Front des artistes canadiens) fee schedule, the activist organization W.A.G.E. (Working Artists and the Greater Economy) has been working since 2008 to certify mostly non-profit American institutions that provide exhibiting artists with adequate remuneration and thereby indicate that they value the labour ofartists.7 7 - See the W.A.G.E. website, wageforwork.com/home. W.A.G.E. demand that institutions spend around 1.3 to 2.3 percent of their annual budget on exhibition fees. Although W.A.G.E. acknowledge that their efforts are ultimately reformist, they reject the positioning of the artist as a speculator. The collective BFAMFAPhD produces reports and teaching tools that raise consciousness regarding the impact of economic insecurity on artists’ lives, including reports on how artists survive in the economy at large, on the distribution of inequity with regard to race, class, and gender, and with strategies for organizing alternative institutions, including artist-run spaces, worker cooperatives, community archives, and solidarity economy initiatives. “What,” they ask, “is a work of art in the age of $120,000 artdegrees?”8 8 - BFAMFAPhD report that in 2014 the average American graduate had a $37,000 student loan debt. The total student loan balance exceeds $1.2 trillion, more than any other type of household debt, with the exception of mortgages. Artists who work to make ends meet are typically educators (18 percent), are unemployed (17 percent), work as managers (9 percent), work as artists (8 percent), work in service jobs (8 percent), work in blue-collar occupations (5 percent), work in business and finance (4 percent), work in science and technology (4 percent), work in medicine (2 percent), or work in various other fields (11 percent). See http://bfamfaphd.com. Similarly, Arts & Labor, a working group founded in conjunction with Occupy Wall Street, have endeavoured to expose and rectify exploitative working conditions. The group’s activities include actions against unpaid internships, information campaigns against non-union contract labour at the Frieze New York Art Fair, and calls to end the Whitney Biennial.9 9 - See the Arts & Labor website,

artsandlabor.org.

womanifesto, 2008. Poster produced for the 2014 fundraising campaign Wages 4 W.A.G.E.

Photo : courtesy of W.A.G.E.

Bryan-Wilson also mentions the groups Artists Meeting for Cultural Change, Artists for Economic Action, Artists’ Community Credit Union, Visual Artists’ Rights Organization, Artists’ Rights Association, Women’s Caucus for Art, Group Material, and REPOhistory. One could also note the work of the Global Ultra Luxury Faction (Gulf Labor Artist Coalition) and, in Québec, Les Entrepreneurs du Commun, who, among other activities, have proposed build-ing a Monument to the Victims of [Capitalist] Liberty in response to the plans by Ottawa’s National Capital Commission to build a memorial to the victims of communism. Slavoj Žižek says that in the pact between the people and the former state socialist regimes, economic shortages made it such that people kept a cynical distance from power but also sought small advantages that made lifebearable.10 10 - Slavoj Žižek, Incontinence of the Void: Economico-Philosophical Spandrels (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2017), 159. Might our efforts to adjust to the neoliberal endgame not result in similar problems? The ideal of communism, according to Marx and Engels, would be such that one could hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, and criticize after dinner, without, he added, ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman, orcritic.11 11 - See Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, “The German Ideology” (1845 — 46), marxists.org/archive/marx/works

/download/Marx_The_German_Ideology.pdf. We could say the same for the artist and worker, as needs in a post-capitalist society would alter considerably the function of art and the status of labour.