Sarah Morris, Machines do not make us into Machines

April 17–June 30, 2019

Photo: courtesy of White Cube Bermondsey, London, U.K.

April 17–June 30, 2019

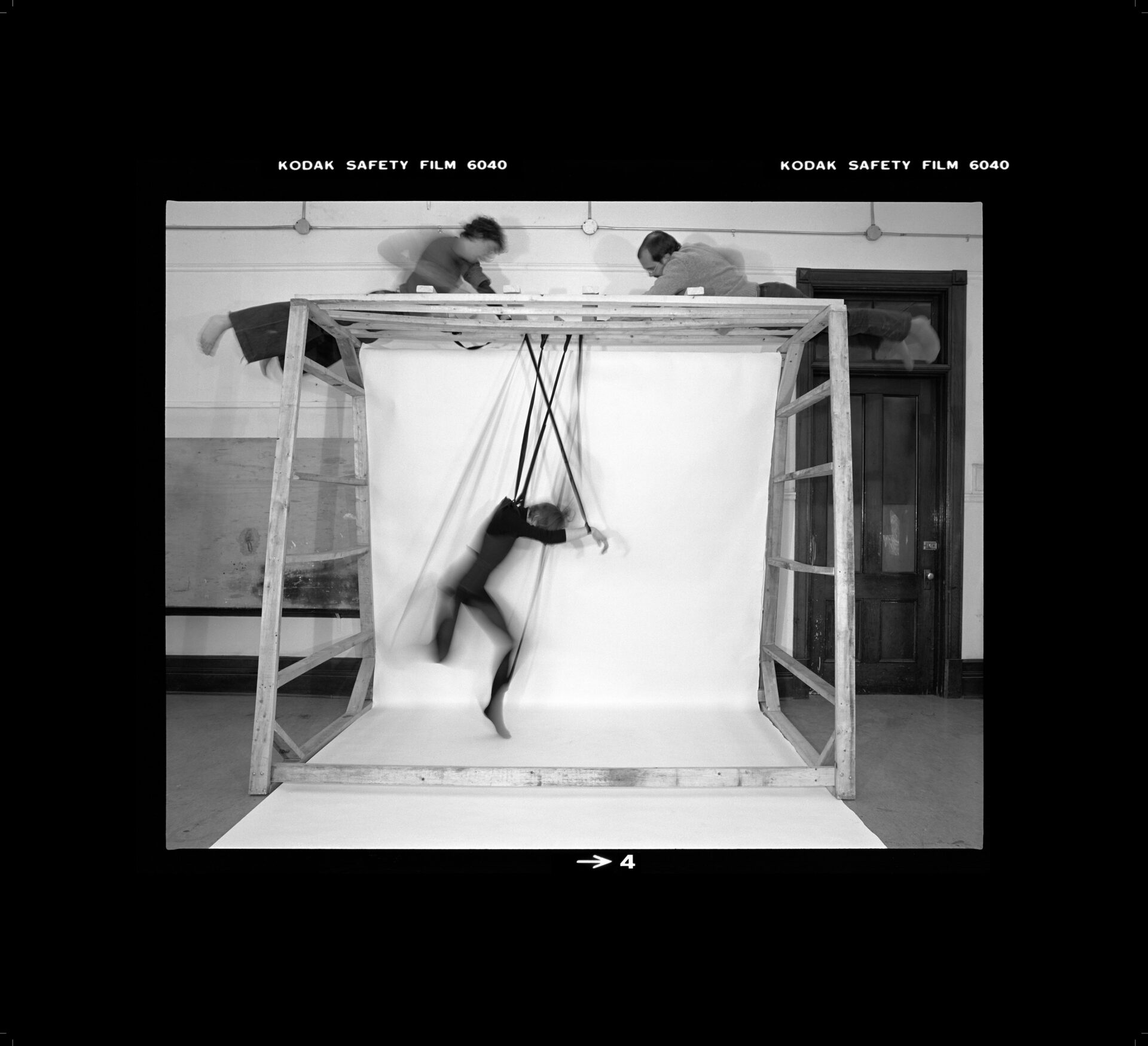

[En anglais] Machines do not make us into Machines, I say to myself, over and over, walking to Sarah Morris’s striking exhibition of new works at White Cube Bermondsey, her first in six years. Inside the cavernous gallery, I say it again; and again as I leave, walking home over the murky, rushing water of the Thames, across the Millennium bridge, which is thronged with people travelling between St. Paul’s and Tate Modern—those cultural bastions of the north and south banks. “The whole bridge sways,” an American tourist says to his friend. “The entire structure is unstable, you just can’t tell when you’re walking on it.” He’s right, in a way, this fellow-walker: when the bridge first opened, in June of the millennial year, pedestrians experienced an alarming lateral sway. The bridge was immediately closed for repairs, and today the sway is no longer; the official explanation that eventually emerged for this unnerving early occurrence is something called “positive feedback,” or “synchronous lateral excitation”—the tendency of pedestrians in large groups to unconsciously match their footsteps to the imperceptible lateral sway of a bridge, thereby amplifying and exacerbating it.

Machines do not make us into machines, no, but some things are beyond our control. The entire structure is unstable, and we are lodged firmly within it, processed, moderated, modulated. But we make our way, dogged, nonetheless, dazzled and consoled, exhilarated by the patterns and processes of our own making. This all too human propensity undergirds much of Morris’s work, belying the hard-edge and slick painted surfaces of her canvases. In Machines, the artist’s signature language of geometric abstraction and an upending use of the grid system as a kind of indexical urban, architectural, capitalist pop is employed to new ends. Where Morris’s focus has often been the city and a sense of place—how power structures infiltrate institutions, geographies, and governing bodies with entropic intent—these new paintings, while writ in a similar visual language, etherise the forces that be.

Créez-vous un compte gratuit ou connectez-vous pour lire la rubrique complète !

Mon Compte