كیف لا نغرق في السراب /To Remain in the No Longer

10 February 2023 to 28 May 2023

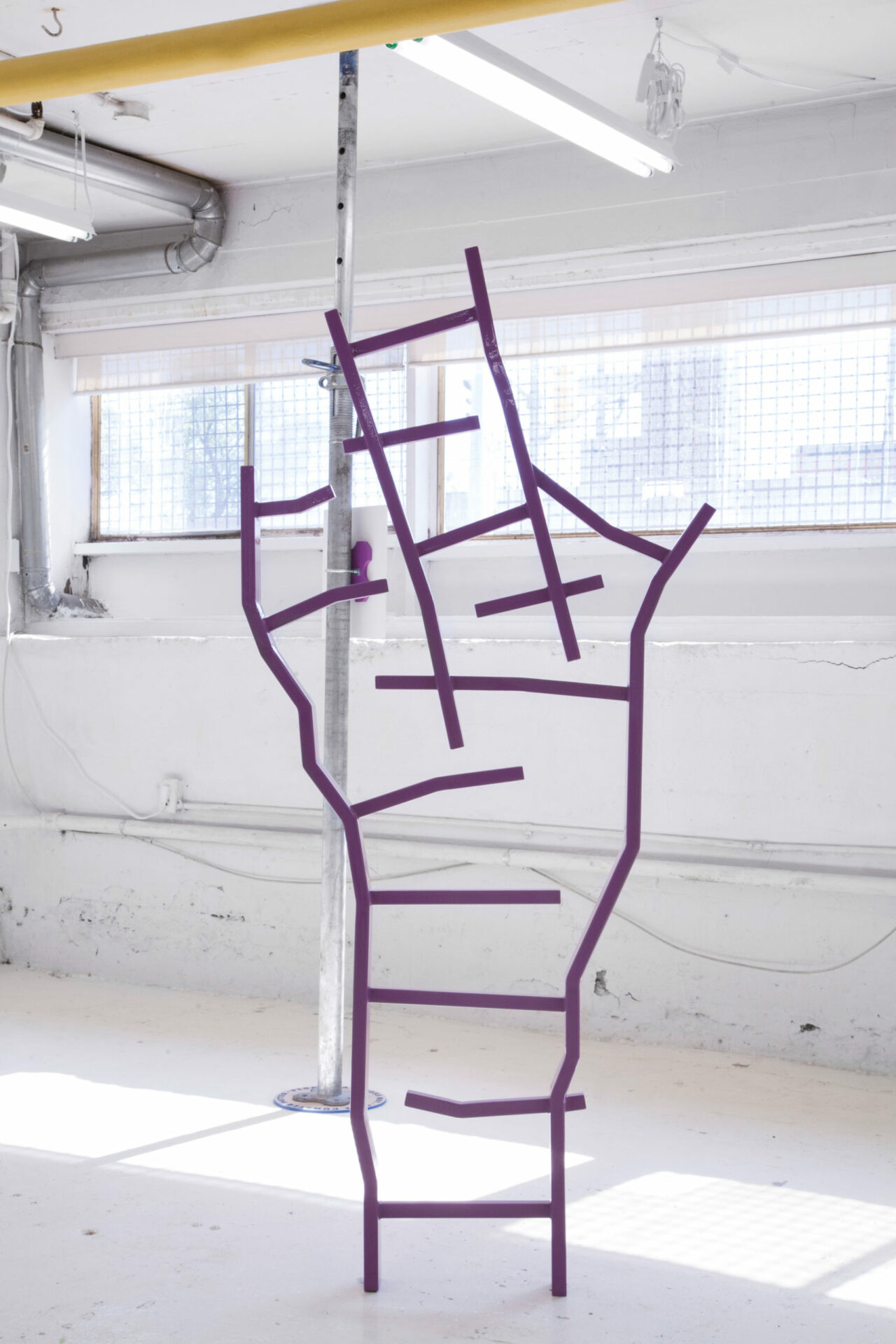

Photo: Oumayma Ben Tanfous, courtesy of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal

10 February 2023 to 28 May 2023

[En anglais] كیف لا نغرق في السراب /To Remain in the No Longer begins, as many films do, with an aerial establishing shot of an urban setting. It is a common cinematic paradigm, this entrance from above; the aerial perspective makes quick work of context while rendering otherwise mundane features into enchanting abstraction.

A soundtrack of helicopter rotors cutting the atmosphere accompanies a moving overhead view of a scarred black-and-white industrial landscape, patterned with buildings and cross-hatched with dirt roads to form a scene that looks like it is either under attack or in the throes of construction. However, as the seconds advance, the intensity of the noise becomes a little too convincing; this, coupled with the abrupt panning of the landscape and the way the camera moves out of focus, causes me to doubt that this view is what it claims to be. The stillness of the setting is too absolute, the resolution is too granular, and the surface is occasionally flecked with material disintegration, so that the aerial perspective suddenly changes scale from that of an overview of landscape to that of an archival image.

Créez-vous un compte gratuit ou connectez-vous pour lire la rubrique complète !

Mon Compte