SODRAC (2009)

Photo: courtesy of the artist & VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

A rumour spreads through the queue. Those at its head become agitated. They discuss loudly with the guard, who smiles at them and gestures with his hands as though he were trying to reassure them. Everyone looks at everyone else. The guard leaves his post and comes towards us to warn us: “The waiting time is approximately 50 minutes.” Taken aback by this, the person beside me repeats: “50 minutes? But what can they be doing in there? Is it that big?” The guard contents himself by smiling mysteriously. My neighbour casts him an interrogatory glance without success, since the guard does not respond. The only explanation provided is written on the wall facing us: “Gregor Schneider Süßer duft.”1 1 - From 22 February to 18 May 2008, the German artist Gregor Schneider presented the installation Süßer duft at La Maison Rouge, Fondation Antoine de Galbert (Paris). The guard receives a message on his walkie-talkie and addresses himself to the visitor standing next to him who squirms impatiently: “Have you read this document?” The man acquiesces. “Perfect. If you agree, write your surname and given name.” The guard gives him a pen and, pointing his finger at the bottom of a sheet, he adds: “Sign here.” Everyone in line quiets down in an effort to hear the explanation. The man complies, looks back at us one last time, and walks down the corridor indicated by the guard. At this point every visitor feverishly awaits the moment when he or she will be invited to read THE document in question and maybe sign it. Finally, the much anticipated moment arrives. On the wall a small sign declares: “As a result of specific conditions required by the artist, the Süßer duft exhibition can only be visited one person at a time. If you are claustrophobic, have cardiac problems, or if you suffer from anxiety in conditions of total obscurity, it is preferable that you do not enter the exhibit or that you do so in the company of another person. We furthermore discourage pregnant women from entering the exhibition. Know that you are under no risk. If you cannot find the exit, wait patiently: a guard knows you are there and will come to get you.”

Total obscurity… No risk… This makes one wonder. The guard has returned and shifts his balance from one foot to the other; he plays distractedly with the walkie-talkie’s antenna. When a crackling sound is heard, he starts and indicates to a visitor that his turn has come by extending to him the form to sign. The man squints his eyes better to grasp the scope of what is being asked of him and begins reading: “Dear visitors, as a result of specific conditions required by the artist, the exhibition Süßer duft can only be visited individually. Since the configuration of the exhibition does not permit conventional supervision, each visitor is invited to assume responsibility for himself by signing the following agreement. The Maison Rouge refuses all responsibility for possible physical or material damage incurred in the exhibition. In signing below, you declare to have been made aware of these conditions.” The man raises his head, twisting his mouth into a grimace. He appears to be upset and embarrassed. He mutters something in the guard’s direction, cracks a weak hint of a smile, and quickly heads toward the art centre’s exit. Stupefied, we watch him leave. The rumour spreads once more through the queue. Visitors stand there, worried and nervous, like divers lined up at the foot of the staircase leading to the high diving board. Waiting time of 50 minutes: in having almost reached our objective, we cannot give up. At the base of the diving platform, we would at the very least enjoy the satisfaction of knowing what awaits us, of seeing others jump in and swim back up to the surface of the water. However, Süßer duft swallows spectators one after another without spitting them back out. Not one returns to tell us. We hear no story to reassure us.

Süßer duft, La Maison Rouge, Paris, 2008.

SODRAC (2009)

Photo: courtesy of the artist & VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

Retreating to the right at the end of the small white hallway there is a door. As he is about to close it behind us, the guard advises in a low voice: “If you do not feel well, do not move. Someone will come to get you.”

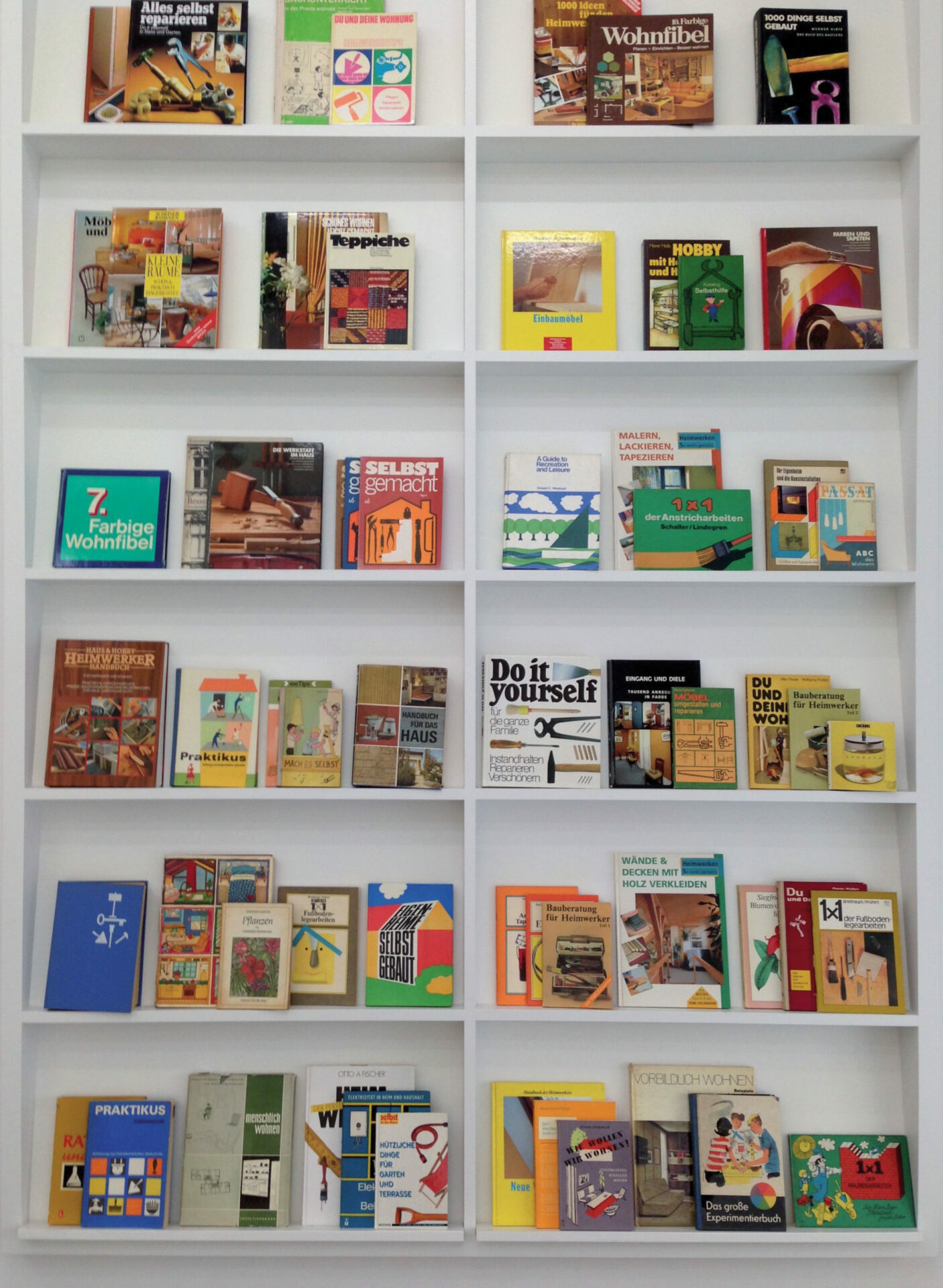

We are now alone in a very narrow corridor that looks like a backstage area: on one side there is the wall of the art centre, white and thick, and on the other a partition raised up several meters high. A little further down, a discreet handle in the partition indicates a passage to another site. Timidly, we push the hidden door in and discover a small room with a low ceiling, dimly lit by an orange lamp. There is another door at the end of this room that opens onto a corridor similar to the one we have just exited. Yet again we come face to face with a door in the partition. As it loudly slams shut, we realize that it is impossible to reopen it.

The room in which we find ourselves “locked in” is completely white. It resembles a contemporary museum space dividing two exhibitions: empty, immaculate, and vast. From the ceiling neon bulbs pour out an intense and overwhelming light. There are several doors, but only one handle. To reach it we must cross the entire space. Our steps resonate. Fortunately the handle turns and the door opens. We then fall into a container. Its sides are made of aluminium. It is hot; the air is stale. Located behind a translucent, plasticized curtain, a handle similar to those found on freezer doors again indicates a new path to follow. Upon opening this door, the change in temperature is compounded by another surprise: the space’s profound obscurity. We must grope around in the dark to find the next exit, and we discover a handle curiously identical to the previous one. A doubt overcomes us: have we retraced our steps? The darkness is complete. As we attempt to follow the length of the wall, our hands and feet run up against emptiness. The space is complex. Upon finally reaching the detour of a partition, the light and a strange feeling of déjà-vu arise simultaneously. In an instant the idea that we must begin the journey anew crosses our minds. In reality, we stand in the exit’s antechamber. A last door “finally” opens onto the museum space. Our return to the secure space is brutal. We no longer expected it. It is a shocking awakening.

The sweet and acrid smell that wafts in from beneath the doors2 2 - “Süßer duft (“sweet perfume”) is the first time Gregor Schneider uses artificial odours in his work, which imperceptibly modify our perception of space, our behaviour, and our mental images. In the exhibition, the visitor perceives two types of contrasting odours. It is a play of olfactory opposition that the artist announces in the scratch n’ sniff exhibition card: the evocative title “sweet perfume” is covered with an opaque, silvery film, which, when scratched, reveals the disagreeable odour of burnt rubber.” Excerpt cited from the Süßer duft exhibition brochure. is the only Ariadne’s thread that spectators can grasp to guide themselves. It fills our lungs and impregnates our nostrils. This smell progressively becomes a projection surface. Certain spectators have compared this smell to that of meat at a butcher shop, and others to that of body odour. We discover it at the beginning of the journey; it surprises us, and the more challenging and prolonged the experience becomes, the more its perfume seems disagreeable. Insufferable, it magnifies the contrasts that saturate our senses.

« White Odour », Süßer duft, La Maison Rouge, Paris, 2008.

SODRAC (2009)

Photo : courtesy of the artist & VG Bild-Kunst Bonn

As aural isolation gives way to the noise of doors that slam shut in seeming condemnation, as the light is either too intense or altogether absent, we have no other choice but to experience the void, our imprisonment, and the labyrinth. Lost in the middle of nowhere, we are urged forward and must always go further just to be somewhere else. “To exit” becomes a primal quest. A meticulous working of matter, colours, and light transforms the space into a scenario and slowly but surely builds anguish.

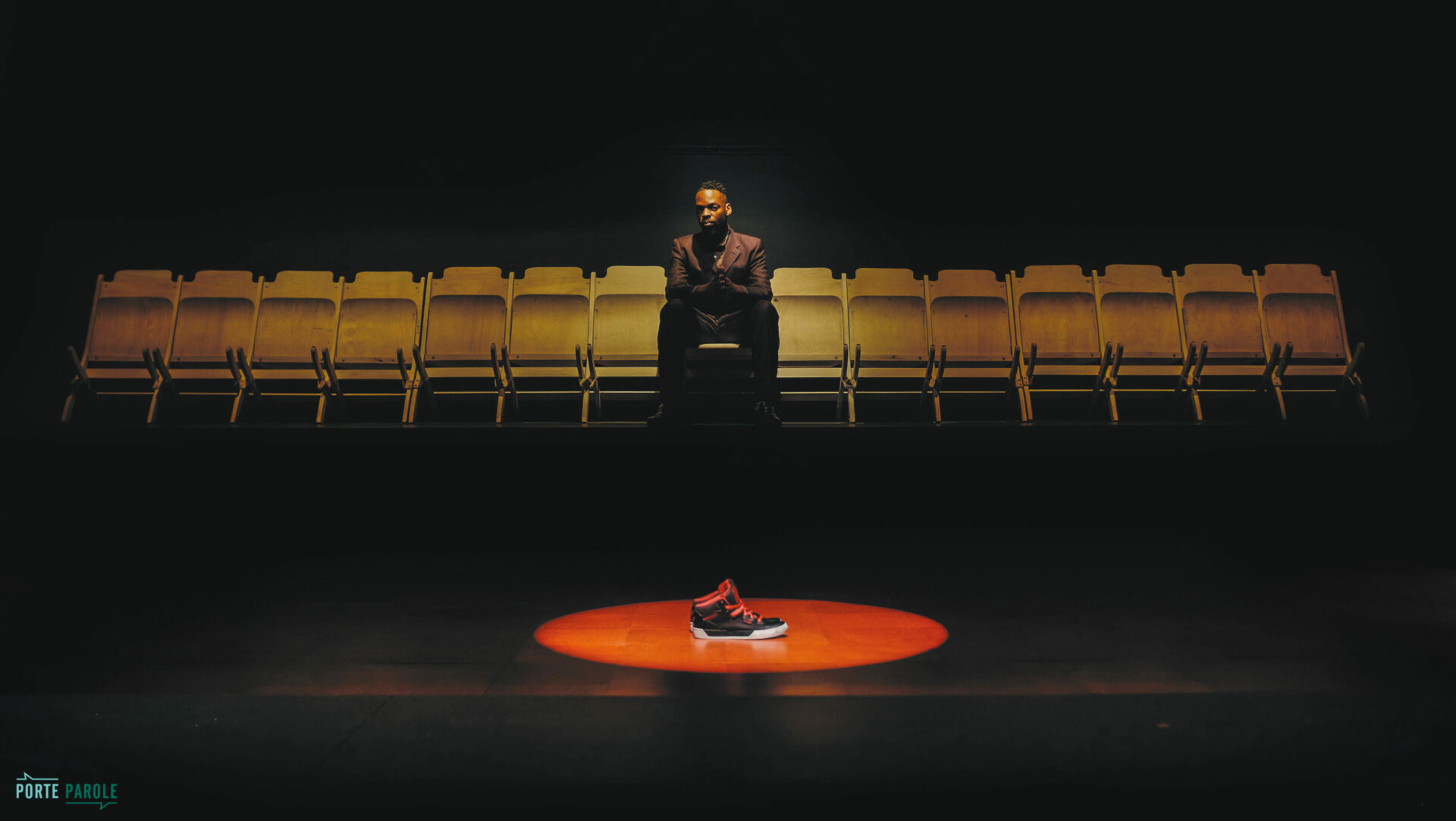

Nonetheless, since the spectator’s suffocation is not the simple by-product of spatial pressures, it is all the more ineluctable. Not only do visitors immerse themselves in a space that dominates them, but they also become engrossed in their own perceptions, which end up engulfing them. The work is analogous to a black hole in space and time. It exists only in the unique and intimate experience of each visitor who has been removed from reality (“reality” is understood here in terms of a shared perception of things). Inside the exhibit, we are definitely alone, “solitary witnesses of (our own) staging” and of the artist’s mise-en-scène. The solemnity of the formal notice, the fulfilment of formalities, the signing of a contract, the dramatization of the entry into the artwork, and, above all, the wait time are all necessary stages to the construction of this experience.

In Süßer duft, the world disappears from spectators’ horizon and spectators disappear from the horizon of the world: they do not know where they are, and those who are on the outside do not know either. The spectator who disappears haunts the memories of those who “remain,” waiting. These witnesses are indispensable. Without their testimony, the disappearance would not take place. Schneider’s artworks are secret, ominous “cells,” unknown, blurry, and unfathomable. The choice of making spectators enter one at a time is therefore far more than an authoritative strategy designed to frighten the public: the artist places spectators in a position to accept their own disappearance. This disappearance of the subject coincides with his apparition in our memories and corresponds to the infinitesimal moment of passage to another state of being. This change in status is as brief and efficient as the short instant during which we walk through an open door, a gateway, or step over a threshold.

Translated from the French by Vivian Ralickas