photo : János Szentiványi, courtoisie | courtesy Terror Házá Múzeum

The spectacle is capital accumulated to the point where it becomes image.

Guy Debord

These days, the word “TERROR” looms large over Andrássy Avenue in Budapest. The text is stencil-cut in full caps on an overhanging black entablature, the shadow of each letter reflected in full daylight over the building’s neo-renaissance façade. The effect of the repetition of the word on both the awning and the building is striking. “Terror, Terror,” one reads. Considered the Champs-Élysées of the city, Budapest’s most elegant avenue starts at Hero’s Square, continues to the famous opera house, and is lined along the way with swank shops, restaurants and 19th-century mansions. Amongst them now stands the “House of Terror” (Terror Háza Múzeum), a museum that chronicles some of the darkest aspects of Hungary’s Fascist and Communist past. It is also featured in every tourist guide as one of Budapest’s main attractions. Yet there are reasons to be critical of the museum’s unexpected popularity.

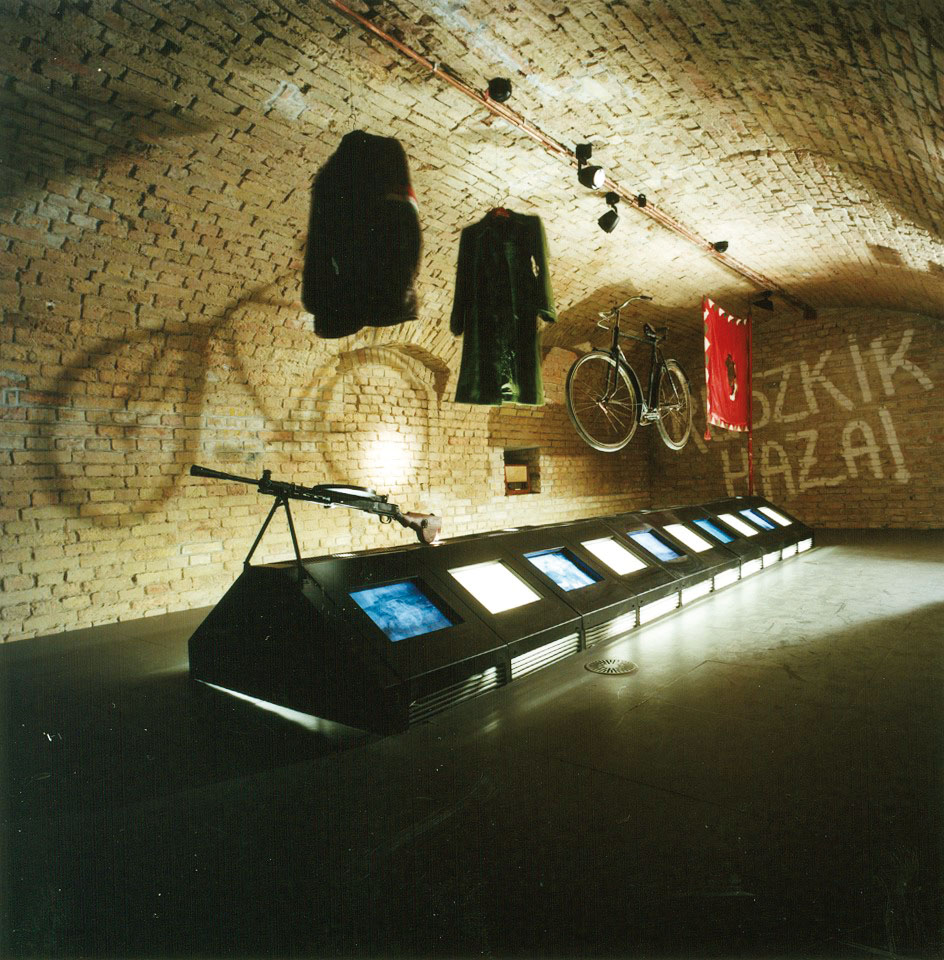

The museum is situated in one particular mansion haunted by an incredible, and incredibly contentious, history. Originally the property of the Perlmutter family, the building became the headquarters of Ferenc Szálasi’s Arrow Cross, the Hungarian far-right party, in 1940. Under the brief but brutal Nazi occupation of Hungary, the basement was used as a prison. When the Soviets liberated, then occupied, Hungary in 1945, the building became the headquarters of the infamous AVO (later AVH) Communist secret police. One bloody regime replaced another in an ironic twist seemingly possible only in fiction; they even continued to use the same basement as a prison. When the AVH left in 1956, the house was renovated, effacing all traces of its heinous past.

The building, which for many Hungarians had become a veritable symbol of terror, was transformed into a museum in 2002. It is intended as a memorial to the victims of Hungary’s two recent dictatorial regimes, including those detained, tortured or killed in the building. Its purpose is reflected in two logos: the Nazi Arrow Cross and the Communist five-pointed star, situated side by side on the building’s façade. Strangely enough, the museum is popular. Since its opening, it has drawn crowds of up to 1,000 visitors per day, with hour-long line-ups spilling out onto the street.

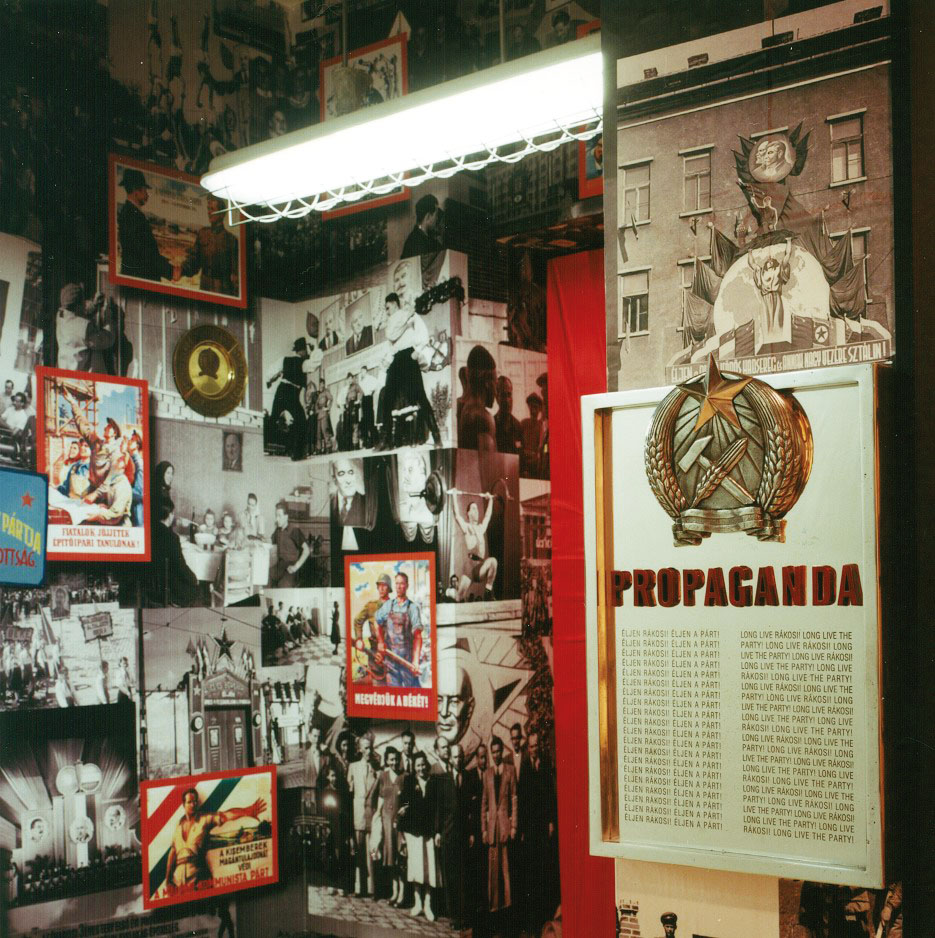

The museum is slick. Its exhibits are sensational, often, I would argue, at the cost of elucidating a clearer understanding of Hungary’s past. Viewers are moved from one display to the next as if through different scenes of a Hollywood blockbuster production. The foyer introduces the museum like the opening credits of a film; one enters a long hallway to heavy instrumental music, and through a passage which bears the insignias of both regimes cut boldly into grand red and black marble plaques. Inside, akin to the classic establishing shot, a main atrium houses an entire Soviet T-54 tank, placed in the middle of a raised pool of black crude oil. Around the tank, spanning the museum’s three floors, are entrances to different exhibits, their doors resembling prison barracks. The tank is framed by a wall with hundreds of blurred portraits of victims etched into metal tiles that form a massive grid spanning the floor to the ceiling. One then enters what would be the main sequence of the film: a winding and varied labyrinth of sets, starting at the top floor, and descending to the basement, each scene more spectacular than the last, illustrating different aspects of sixty years of brutal oppression: the expulsion and murder of the Jews, the starvation of the peasantry, the brief liberating force of the 1956 revolution and its suppression, the gulag, and the list continues. Finally, during a painfully slow elevator descent to the basement, a video plays an interview with a former janitor as he matter-of-factly recounts how executions were carried out in the basement. As if further details are needed to complete the picture, one then tours a selection of recreated prison cells in the chambers below, detailing the cruellest methods of confinement, torture, and murder employed during both regimes.

The analogy to cinema may not be far off the mark. The museum was designed by Attila F. Kovács, a film designer-cum-architect perhaps best known for his work on the set of the film Sunshine (2000). After the success of the House of Terror, and as part of the increasingly popular civic trend of promoting cultural tourism, he designed another terror museum called “Memory Point” in Hódmezóvásárhey, Hungary, a small town located near the Romanian border. It has the same sensational presence.

photos : János Szentiványi, courtoisie | courtesy Terror Házá Múzeum

Questions of exactly how terror can or should be represented seem central here. My concerns are both with the ethics of representation as well as the effectiveness of the museum in imparting a deeper understanding of how such exercises of power can occur in society. How can we represent the tragic errors of history without defaulting to the spectacular, the misrepresented, or the readily consumable vision of the past that presents terror as something clearly defined, circumscribed, and most dangerously, unrepeatable?

Guy Debord notes in La Société du spectacle that society has become one in which human relations are no longer directly experienced but become mediated in their spectacular representation. “The whole life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. All that once was directly lived has become mere representation.”1 1 - Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (New York: Zone Books, 1995), 12. Debord’s observation that contemporary society was caught up in the logic of the “spectacular” continues to be relevant today, especially in such questions of representation.

Through Kovács vision, terror is indeed represented in its most spectacular form, but rather than being immersive, the effect is distancing. For example, in the first room, a bank of twenty video monitors plays gruesome black and white film footage from WWII—uncredited clips played in looped sequences. The sound of the films overlaps until it hangs in the room like an ambient hum. To add to this cacophony, heavy instrumental music fills the air, its repetitive beat resembling the sound of Eastern European techno more than a reverent classical score, as the museum publicity describes. The WWII footage, we can assume, is not intended to be seriously studied, but glossed over as an “effect.” Likewise, visitors’ movements through the exhibits are so highly choreographed that any chance of prolonged engagement with the material seems impossible. One follows a long line of visitors in a procession from one hall to the next. As in cinema, the combination of impressive audio and visual effects, even with the most sober subject matter, can affect pleasure. The conflict resides in this very tension between the intended educational aspects of the museum, and its function as entertainment.

Other monuments which deal with tragedy through unconventional strategies of representation often prove more effective. Consider the Holocaust memorial in Berlin. The “Monument to the Murdered Jews of Europe” is a field of 2,711 grey stone slabs situated in the centre of the city. Designed by the New York based architect Peter Eisenman, the stones are placed on sloping, uneven ground in an undulating wave-like pattern. In some places, the ground drops to 2.4 metres below street level. Walking between the stones, one descends further into the maze until view of the city disappears. There is no single, prescribed path through the memorial site. Visitors can enter and exit from all sides, any time of the day or night, and wander through the maze, as though visiting a graveyard with nameless tombstones. Eisenman fought to keep the stones unnamed, choosing to maintain the relatively abstract qualities of the memorial, and much is left open to interpretation. It is impossible to negotiate a direct route through the memorial; one often loses one’s path amongst the stones, loses sight of the people one entered with, loses the sense of the city, and the effect is disorienting on a physical, visual, and auditory level as even the sounds of the surrounding streets become fractured. But it is the sensation of being lost that is unique and deeply resonates with a history in which people were separated, displaced, and disoriented. As a viewer, one has to work at understanding the memorial in Berlin simply because one cannot engage the work passively. Whether acting reverently or irreverently, one is nevertheless acting to make meaning of the work and that meaning is not so clearly circumscribed in advance. No such opportunity for critical reflection arises in Budapest’s House of Terror. At the best, exhibits are sensational, and at their worst are pleasurable and entertaining. Either way, the relationship to material is a relatively passive one.

To add to the conflict, the House of Terror has been mired in controversy from the start, fielded on a few fronts, and arguably symbolizes the highly charged political climate in which the museum was consecrated.

photos : János Szentiványi, courtoisie | courtesy Terror Házá Múzeum

First, the museum has drawn strong criticism from the Jewish community, on the grounds of disproportionate representation between the two regimes. Indeed, only two of the over two dozen rooms are solely dedicated to the Holocaust, leaving visitors with the impression that Communism was a far worse evil. Furthermore, by presenting all its victims and victimizers as equal, it diminishes the uniqueness of the Holocaust, not to mention, the Communist era. Finally, by representing Hungary as a victim of Germany rather than as one of its accomplices, it is said to continue “. . . a trend in which right-wing Hungarian historians are whitewashing Hungary’s role in the death of some 550,000 Hungarian Jews.”2 2 - Michael J. Jordan, “New ‘House of Terror’ Raises Fear for Hungary’s Jews,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, 20 April 2007. <http://www.jewishsf.com/bk020809/i42.shtml>

To further complicate the matter, critics argue that those who created the museum had openly political motivations. It was inaugurated with great fanfare by the previous right-wing nationalist government of Victor Orban in the final heat of the 2002 parliamentary elections, weighing into the middle of a closely contested election campaign. Many see the museum as an attempt to connect the image of Orban’s rival Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) with the former Communist regime, representing it as the historical legacy of the Socialists. The criticisms are not entirely unfounded. For example, Mária Schmidt, who has been the director of the museum since its opening, was Prime Minister Orban’s chief advisor from 1998 to 2002. The concept of the museum, as the brochure reads, was hers, and she makes no apologies for the museum’s political slant. “Is there anything in history that is not related to politics?”3 3 - Thomas Fuller, “Stark History / Some See a Stunt: Memory Becomes Battleground in Budapest’s House of Terror,” International Herald Tribune, 2 August 2002. <http://www.iht.com/articles/2002/08/02/budapest_ed3_.php> she asks rhetorically. The museum failed to win Orban the election in the end, but it continues to represent, for many, an example of propaganda, a museum designed with the “intent of moving people in calculated ways to precise political beliefs.”4 4 - Lisa Cartwright and Marita Sturken, Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 363 Andras Mink, a Hungarian historian, was quoted as saying that the House of Terror “brings down the memory of terror into false, cheap and repulsive political propaganda.”5 5 - Fuller.

It would be contentious, to say the very least, to compare the House of Terror to Disneyland. Yet there is something in this comparison that resonates with fundamental questions of representation and power that I would like to draw out. Aside from the obvious differences in content and intention, the similarities in the modes of presentation are striking: the use of blatant symbols, the high production values, the sensation of pleasure in the full scope of audio-visual resources used, just to name a few. Further, as Jean Baudrillard describes, Disneyland presents an image of America perhaps more real than America itself: “Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real, but of the order of the hyperreal and of simulation. It is no longer a question of a false representation of reality (ideology), but of concealing the fact that the real is no longer real. . . .”6 6 - Jean Baudrillard, “Simulacra and Simulations,” Selected Writings, Mark Poster, ed. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988), 166-84.

That Disneyland is more real than the country it ideologically represents, is more than a contradiction. As Baudrillard suggests, the representation of Disneyland as imaginary masks the simulation, thus concealing the fact that the real no longer exists. In a similar twist, the inherent contradiction in the House of Terror is that it is an exercise of power itself in a mode similar to that which it seeks to critique and ultimately deconstruct.

By presenting a spectacular representation of the official history of both totalitarian regimes, the House of Terror indulges aspects of some of the worst atrocities of the past century. At the same time, it masks the truly horrifying facts that much of that history is still hidden and cannot be uncovered; gaps in our knowledge of history are perhaps most unsettling. Finally, by situating this history decidedly in the past, the museum ignores the legacies that such events mark on a country, and the ways in which such regimes continue to reproduce themselves today in very real terms. Monuments need to be as critically reflective of their modes of representation, as they are of the tragic events they depict.