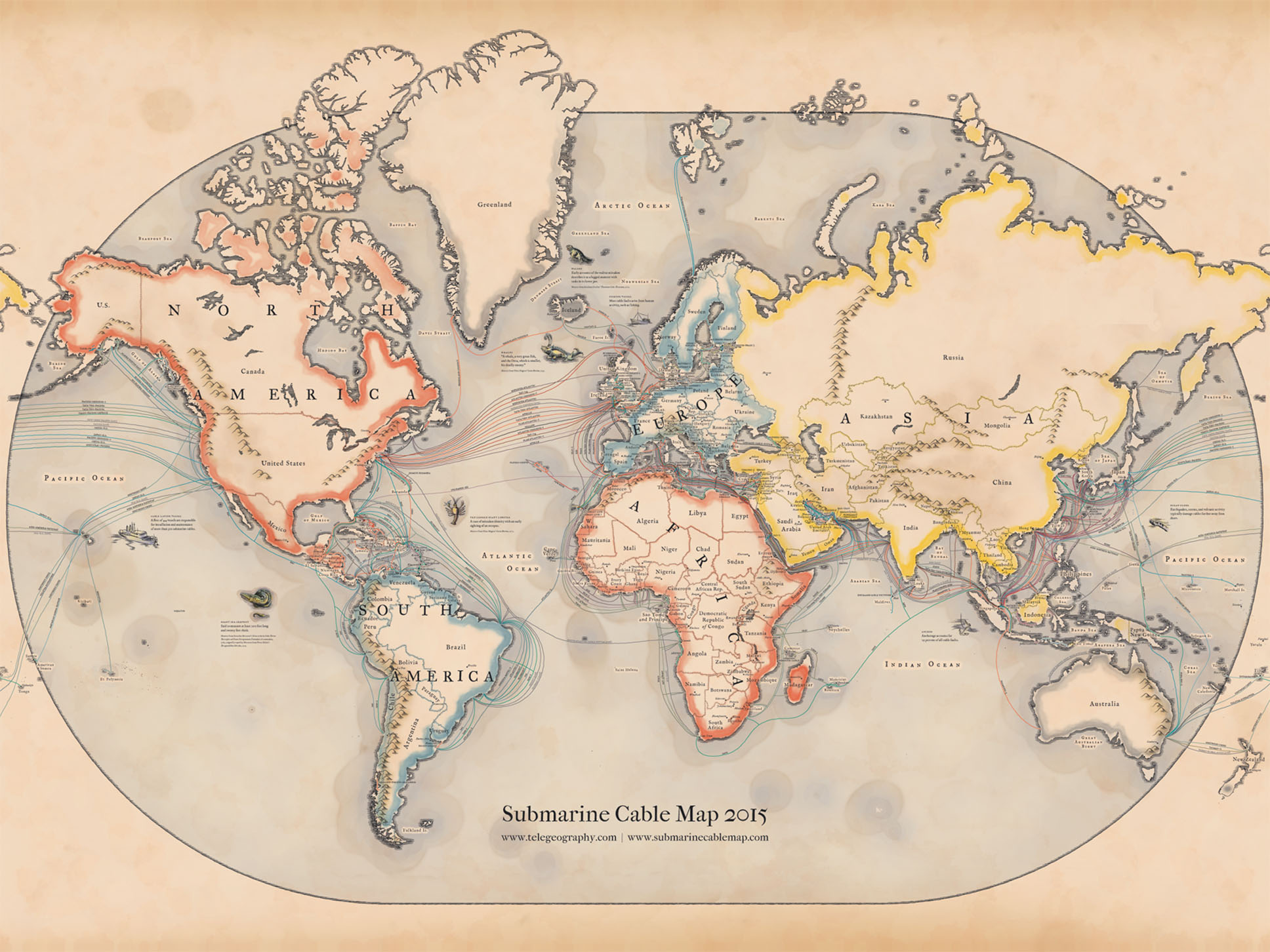

Photo : © TeleGeography

Offshore Havens and Supra-Jurisdictional Space

The theory and design collective Metahaven has produced much of its work around data: their transparency or lack thereof, their ownership, their use by states and corporations, and their power. In its two-part article “Captives of the Cloud” (2012), Metahaven uses the term “supra-jurisdiction” to describe how, under the Patriot Act, the United States government has the authority to access information hosted by any data centre owned by a company registered in the U.S.1 1 - Metahaven, “Captives of the Cloud: Part 2,” e-flux Journal 38 (October 2012), http://www.e-flux.com/journal/captives-of-the-cloud-part-ii/. The Patriot Act extends the government’s authority beyond its own territory and citizens, granting it power over some of the largest search engines in the world, including Google. In a similar vein, Benjamin Bratton describes how conventional models of map and territory have been reworked on a planetary scale, and he calls this new political formation a stack: a “vast software/hardware formation, a proto-megastructure of both bits and atoms, literally circumscribing the planet, which, as said, not only perforates and distorts Westphalian models of State territory, it also produces new spaces in its own image: clouds, networks, zones, social graphs, ecologies, megacities, formal and informal violences, weird theologies, each superimposed on the other.”2 2 - Benjamin Bratton, “On the Nomos of the Cloud: The Stack, Deep Address, Integral Geography” (2011), bratton.info/projects/talks/on-the-nomos-of-the-cloud-the-stack-deep-address-integral-geography/. The stack structure of physical and telecommunications infrastructures folds every transnational corporation into a tangled web of jurisdictional entities. It would not be doing the power dynamics justice to place the power solely in the hands of the United States, as Metahaven implies. Indeed, representing it as such risks negating many crucial bodies that are implicated in this vast infrastructure, as well as glossing over the pivotal understanding that this formation shifts depending on the other jurisdictional and corporate interests with which it overlaps. For example, if the United States wanted to shut down a data centre outside of its borders, it would require the consent of the government of the nation in which these data centres are located, and of the various corporate and private stakeholders involved. Therefore, although the United States may exert a significant pressure point, it does not have sole discretion in the matter.