No Future ?

No Future! was chanted primarily by a generation without markers, labelled only retroactively as “X” by Canadian novelist Douglas Coupland in 1991.2 2 - Douglas Coupland, Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture (London: St. Martin’s Press, 1991): 56. Gen-X kids came of age at the apogee of the Cold War, which coincided with the first wave of global market deregulation — signed in the U.K. by Thatcher and Reagan in the U.S. — which proceeded to enrich the already wealthy and freeze the wages of ordinary people for decades to come. But rather than lament this bleak future, some learned through punk to disdain the dream of prosperity that would never come to their shores, to arrest their desire for the glamour of commercialism. If one’s future integration into society was assured from a young age through good education and good manners, now, without hope of benefiting from this deregulated future, punks certainly felt no incentive to politely condone it—on the contrary.

Unsurprisingly, the word punk was first uttered as a derogatory term, referring to prostitutes, petty criminals, and other members of an underclass demoted in social status for ignoring bourgeois protocols. But once appropriated to beckon the transgressive rebel and iconoclast, punk’s vacant future now stands as a symptom, a cogent outcome of corporate greed. When punk attitudes become forms of protest, their skirmishes strangely resonate with the quixotic conduct of May ’68 and the writings of Debord, Deleuze, and even Badiou. Ergo, is dissent also central to French thought because of its callous use of the word futur (defined as an imaginary, fictitious time projected beyond the present, as opposed to the adjacent term avenir, which points to actualthings-to-come)?3 3 - See Philippe Meyer’s essay Le futur ne manque pas d’avenir (Paris: Gallimard, 2000) for a more elaborate differentiation of the two terms. This nuance denotes a more intricate understanding of the future tense and clearer boundaries between imagined and concrete events coming after our evanescent present.

This assertion that the future will always be financially better off is again predicated on the fallacies of permanent growth and progress.

The craft of speculating on the conditions of future generations was studied intensely within science fiction, a literary and filmic genre sparked by the wonders that the industrial revolution was expected to unlock. But the scenarios concocted in Sci-Fi now suffer from an ever-shortening foresight, as we move toward present-day works: from Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men (1930) anticipating human life in the next two billion years, to the Star Trekfranchise (1966–present) portraying space explorers between the twenty-second and twenty-fourth centuries, to recent cyberpunk thrillers, initiated by William Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) . This last set of movies and novels depict near-future scenarios, which are flipping in quick succession to calendar dates of the past, such as Blade Runner(1982) and its timeline set in November 2019. Cyberpunk thus distorted our expectations of a stable past, present, and future and demonstrated that “the future” of the 1950s (filled with clunky robots and big-brained aliens) was utterly different from “the future” of the 1990s (operated by genetically modified post-humans and wet-ware hackers).

More complex and socio-politically convoluted, Richard Fleischer’s dystopian film Soylent Green (1973) summons topical issues of unfettered pollution and overpopulation that trigger the collapse of agricultural systems in a fictitious 2022, forcing humans to (spoiler alert) engage in cannibalism. Such thinning out of the timeframe between factual present and speculative futures brings forth a sense of concern and urgency, voiced by Extinction Rebellion and countless other activist assemblies. Outdated incremental change, as professed by centrist politics, only saves the planet for our children-to-come and conveniently serves as the event horizon of a distant futurity to be pursued but never attained. Against this, the ground-breaking reforms prophesized by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal and Greta Thunberg’s 2019 climate action speech at the United Nations plead for actions taking effect right here, right now4 4 - Visit npr.org for full transcript of Thunberg’s 2019 UN speech.

Punk Sociology author David Beer links aesthetics with DIY creativity and no-nonsense semantics, measuring punk gestures by their degree of authenticity, sarcasm, and Fear of Selling Out(FOSO).5 5 - David Beer, Punk Sociology, (Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014): 20-24. To these criteria I would add a sharp sense of timing and placement, as incisive as when the Sex Pistols crashed the British monarch’s silver jubilee in 1977, singing God Save the Queen while cruising the Thames River before the Houses of Parliament. Occupy Wall Street protests were orchestrated, with similar aplomb, in reaction to the bank bailouts of 2008. Often discredited for spouting unclear demands and a delayed response, Occupy was nonetheless instrumental in steering the public’s anger away from government officials and toward the real decision makers of the day. By staging its protests in front of Wall Street and not the White House, Occupy nonverbally spoke truth to the hegemonic powers that now lie, undisputed, in corporate money.

In today’s muddy political climate, elusiveness is not a liability but an essential asset. Occupy and others need greater fluidity to master urgent actions and ad hoc invention rather than committing to set-in-stone principles, which are much easier to control, discredit, and topple. Punk’s utter disregard for future betterment effectively channels such actions, just as Edgar Olguín’s contempt for decorum empowered his response to the mass kidnapping and execution of a hundred students in the Mexican province of Guerrero. His photographic series Poner el cuerpo: sacar la voz (Showing One’s Body, Raising One’s Voice, 2014–2015) pictured naked men and women in public spaces, scribbled with protest slogans like living placards; he plastered the resulting images across social media to vent his outrage in a most viral yet sincere manner.6 6 - See Olguín’s 2014 project on Tumblr:< https://ponerelcuerpo.tumblr.com >.

Poner el cuerpo: sacar la voz, 2014-2015.

Photo : courtesy of the artist

Art-making, for punks, requires a love of living dangerously in the moment and a tolerance for ambiguous levels of success. Pussy Riot’s breakthrough performance in Moscow’s Red Square captured the world’s imagination in 2012, as they delivered songs such as “Putin is Wetting Himself” while wearing brightly coloured balaclavas. The collective’s leaders, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina, paid dearly for these actions, as they were arrested for hooliganism and spent two years in jail for this and other stunts. However, they have since enjoyed much recognition from the art world, including high entries in both Art Reviewand Artnet’s list of most influential people. Ironically, many detractors discredited Pussy Riot for allegedly commodifying the art of protest once they reached wider audiences. French duo Claire Fontaine has weathered this delicate balance for years, deflecting accusations that revelling inside art markets would disqualify its contempt for capitalism. Claire Fontaine’s response highlights every artist’s dilemma, as both critics and enablers of high-end gallery systems: “Inside, outside, these are things we don’t understand. Who says that? There is no such thing that is defined outside of capitalism anymore.”7 7 - “Claire Fontaine by Anthony Huberman,” Bomb, no. 105 (Fall 2008), accessible online.

The Litany of Curfews, performance, L’OEil de Poisson, Québec, 2019.

Photo : Etienne Boucher

Spunkt Art Now, a project curated by Sébastien Pesot in which I have been involved, also reactualizes punk in twenty-first-century art. As Pesot argues, “We need to do more than regurgitate the scene’s longstanding slogans. Simply proclaiming yourself punk is so not punk.”8 8 - Excerpt from Sébastien Pesot’s Spunkt Art Now manifesto, published at La Fabrique culturelle: <www.lafabriqueculturelle.tv/ capsules/12461>. Likewise, Spunkt ally and feminist collective B.L.U.S.H. mixes the rawness of punk with ecological concerns. Its performance The Litany of Curfews(2019) incorporates audio samples of French marine explorer Jacques Cousteau addressing the pollution of oceans as early as 1970. His voice evolves over soundscapes of whale songs,live effects, and pre-recorded drum and guitar riffs, while Annie Baillargeon, Isabelle Lapierre, and Marie- Hélène Blay slowly unload an enormous bag of plastic refuse like a toxic piñata.

B.L.U.S.H. intermingles environmental anxieties from the past with our own fears of the future collapse of the biosphere. As a result, the trio punctures our modern conventions of linear and progressive time, belittling the dogma of growth to integrate it back into natural cycles of emergence, regress, and rebirth.

In these cyclical efforts to conserve nature, it is now the eco-artists who are called “conservative” for resisting the “progress” of laissez-faire economics. The seemingly benign interruption of May ’68 here finds more traction when joined with other historical rounds of unrest: Gandhi’s Salt March of 1930, the Selma protest of 1965, Tiananmen Square in 1989, Arab Springs in 2010, Black Lives Matter in 2020, and more to come. Especially since they have morphed to virtual entities, the tables have turned on formerly conformist business leaders, who now embrace innovation and disruption to exacerbate the cravings of users with an unquenchable thirst for new apps and devices. And yet, technology trends prescribing the future are wrongly perceived as predictions. While pushing the widespread use of networks as essential tools for the coming decades, the digital revolution made a fortune from this kind of fortune-telling, and it foreclosed our ability to think futurity otherwise. The catchphrase The Future is Now epitomizes the aspirations of a consumer market to shackle things-to-come onto a predestined fate. But is the future really just a misnomer of the present? No, not really. This is only clever posturing, and punks hate posers. Even Google economic consultant Hal Varian downplayed this conflation: “All the data in the world can only measure correlation, not causality.”9 9 - Hal R. Varian, “Beyond Big Data,” Business Economics 49, no. 1 (2014): 6.

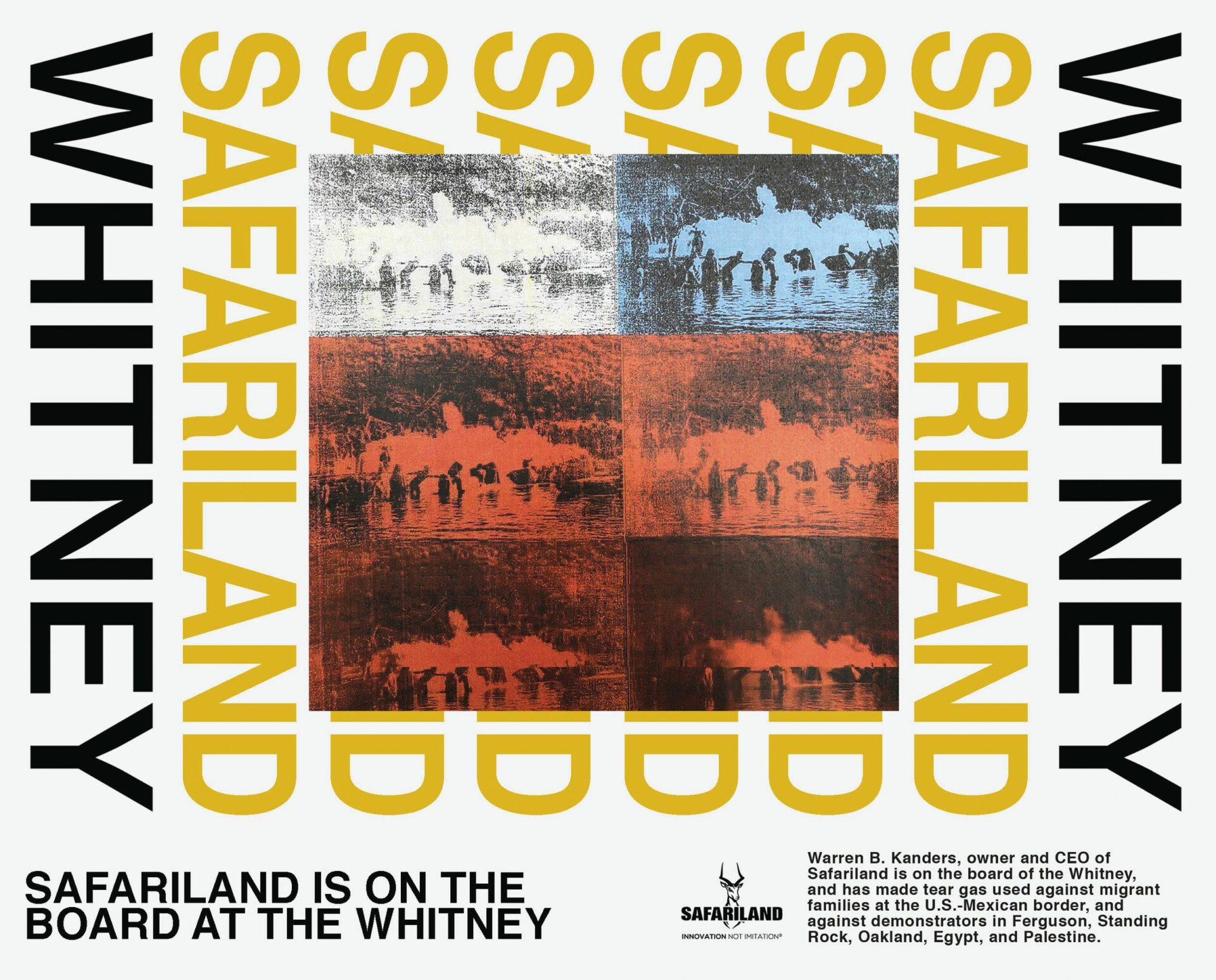

The upcoming ventures of AI surveillance, hyper-automation, and Facebook money are now posited as essential, inevitable, and foretold as economically benevolent. This assertion that the future will always be financially better off is again predicated on the fallacies of permanent growth and progress. Baby boomers may have lived in such a gilded age of inflation, but millennials woke up from this investor’s dream to a nightmare of student and mortgage debt. Conversely, emerging groups like New York- based Decolonize This Place (DTP) have put degentrification at the centre of their mission statement. Pointing the finger at both artists and galleries for moving into low-income neighbourhoods and forcing local residents out, DTP denounces the austerity measures that cut social housing, education and health programs. Since 2016, DTP’s annual demonstration on Columbus Day has challenged the necessity to toggle between artist and activist modes, when consolidating the dispersed anger of Indigenous, Black, and other communities affected by post-colonialism into more cohesive art campaigns. In December 2018, Amin Husain and Nitasha Dhillon headed DTP’s drive to denounce the Whitney Museum’s vice- chair, Warren Kanders, for his association with Safariland, an arms manufacturer deploying teargas at the Mexico-U.S. border, which led to his resignation.

Poster denouncing a member of the Whitney Museum board of directors who is president of Safariland, 2018.

Photo : courtesy of Decolonize This Place

Fittingly, creators are now mobilizing to shape a survivable legacy of their own making. Before being accused of selling out, as Pussy Riot and Claire Fontaine did before them, DTP and others need to think of system-wide approaches to appropriate the present, as it slips into the future. This involves removing artists from the mechanisms that codify them as commodity producers, akin to the heteronormative behaviours that reduce men and women to their procreative roles: making babies to increase the tally of workers, soldiers, and consumers. These social contracts grease the wheels of productivity that build and sustain the foundations of control and dominance in capitalist empires. Punk’s anti-perennial impulse rejects the utilitarian mindsets of production and re-production, forcing every individual to consider the prospect of jouissance — of self-realization in the present — and renounce the blind hope in a redemptive futurity that will forever postpone our sense of purpose. Little Orphan Annie was right to sing “tomorrow you’re always a day away.” If only our societies could sidestep the techno-fetishism that fuses the then and the now, we might be able to keep an open mind about the multiple paths of things to come and dare to improvise when facing the unprecedented, instead of haphazardly planning for the unpredictable.