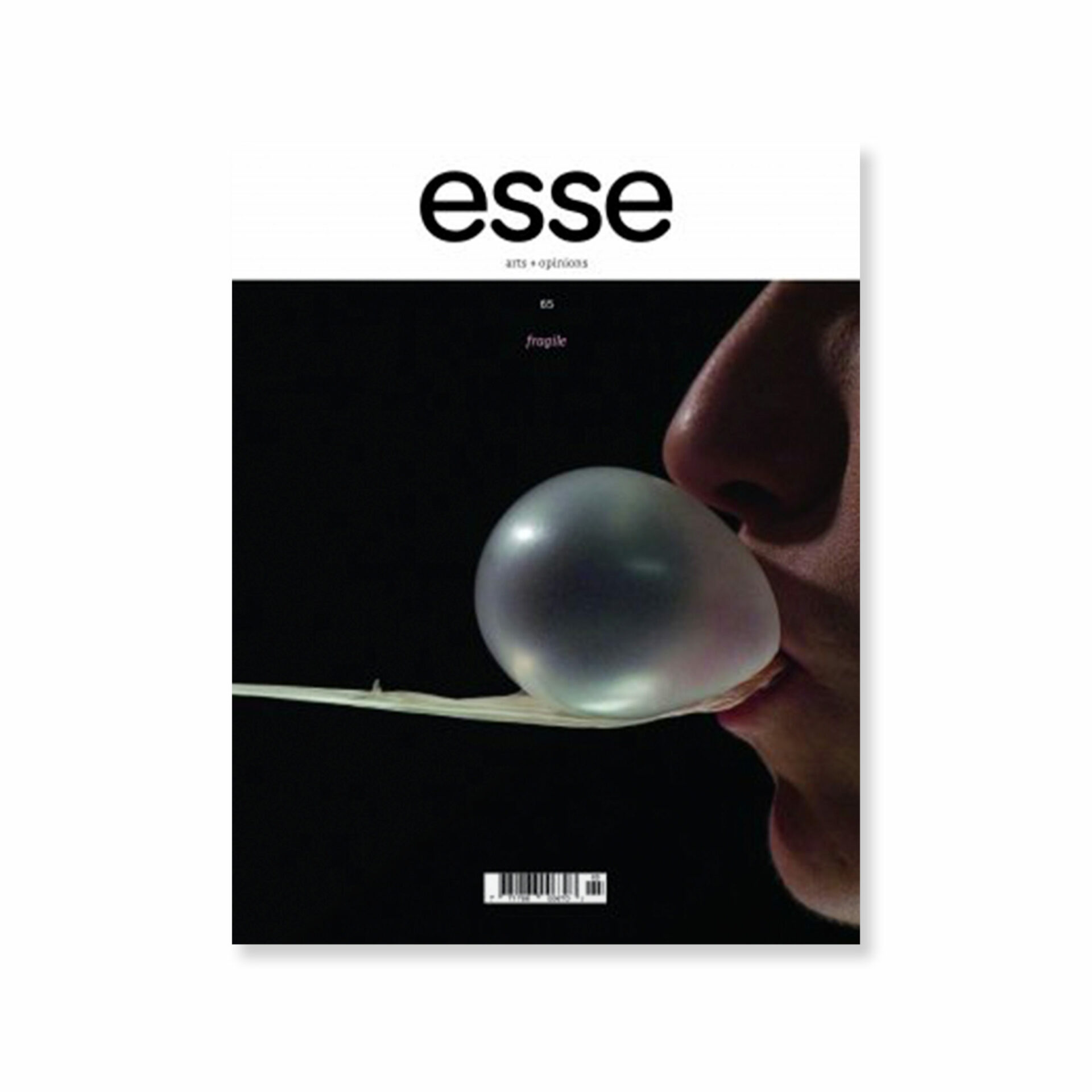

photo : Paul Litherland

An examination of the notion of fragility that caracterizes certain current artworks leads me first to raise the issue of art’s durability. We know that permanence, preservation, and restoration are important concerns for museums. An extreme and paradoxical example of this fight against the passage of time can perhaps be found in the presentation of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa at the Louvre, the ultimate temple of durability. Under the constant surveillance of a security guard watching out for prohibited camera flashes and eventual vandals, the painting is carefully locked inside a secure display case. After having slid through the mass of visitors gorging themselves with the work, we risk being disappointed with the result of our aesthetic experience, if there is one to be had at all. The security precautions and the tinted display case radically distance us from an observation of the painting in a more traditional context, i.e., simply affixed to the wall. Thus, the actual experience translates into a staging of the limitations of our access to the work under the pretext of its preservation from the ravages of time. The paradox of this situation orchestrated by the museum is based on the fact that, far from being let down by their visit, amateurs seem even more fascinated by this piece whose protection—in the manner of an institutional pedestal1 1 - If the classical stand showcases a sculpture in the manner of a pedestal, the extreme protection offered by the museum insidiously participates in the valorization of the painting. —is made highly explicit. Its fragility therefore exacerbates its precious character. Here, the museum offers not so much an aesthetic experience of painting as a fetishist consumption of classical art fed by our fascination with achievements that have conquered time and with the artists that reach towards immortality.

In spite of all the state-of-the-art techniques that allow for the maintenance, restoration, and preservation of artworks, in practical terms it is impossible to extend their lifespan indefinitely. How then can time be challenged? A striking figure of conceptual art, Daniel Buren sets out the path for the existence of his works by instating his “warnings.” Accompanying the sale of each of his pieces, these documents articulate among others the procedure for restoring his work. This contractual strategy imposes upon the buyer the respect of precise rules so that the acquired artwork preserves the artist’s signature.

If we leave aside certain conceptual practices that remove the work from its tangible limits and, by extension, from its physical alteration, we are compelled to notice that the art market is marked by this desire for durability. Collectors thus indirectly participate in the planning of the artwork’s surveillance in the creative process. Although it is often independent from the aesthetic result, the choice of time-resistant inks and papers can constitute a qualitative criterion in the context of appraising the value of a photograph, for example. Practices such as performance are almost always systematically accompanied by documentation, a potentially marketable trace. Insofar as media works are concerned, due to ever-increasing technology updates, they continue to create new conservation problems.

If classical art tends to evoke immortality for us, current art makes us confront our desire to control the present. Communication technologies that generate all types of stimulations in real time permit an almost instantaneous reaction and offer us greater control in different everyday contexts. Through this fascinating tension between classical and current art, practices of a more discreet nature appear, seeming to draw their strength in opposition to the spectacular. Furthermore, in our contemporary context where we are constantly invited to interact, to personalize our experience and to control a maximum of parameters in our environment, is it not unnerving to find oneself faced with a fragile work that, without inviting us to intervene, forces us to confront our free will?

Presented in the context of the Mois de la Photo, Chih-Chien Wang’s Le nid can seem disconcerting since here the notion of photography as a tangible object, a present instant captured and made immutable, is absent. First and foremost conceived of in terms of a short-run installation, the evolution of this project was never lacking in surprises. The fragility of the piece provoked unforeseen interventions that finally brought an unusual depth to the project, generating another type of aesthetic experience.

photos : permission de l’artiste | courtesy of the artist

The installation created by the photographer2 2 - Although he uses photography on a regular basis, Chih-Chien Wang does not consider himself, strictly speaking, as a photographer. It is in the context of the Mois de la Photo that I take the liberty of defining him as such. was made up of fragile elements without lasting value: walls made up of cardboard boxes grafted to the pillars of the monumental concrete structure that overhangs the “parc sans nom.”3 3 - This “nameless park” is a wasteland situated in the Plateau Mont-Royal burrough in Montreal, between Saint-Laurent and Clark, and Arcade and Rosemont streets, under the Van Horne overpass. This assembly of humble materials does not fail to call to mind a makeshift shelter. Microphones placed under the viaduct amplified the vibrations caused by cars in loudspeakers. The result was strangely sterile. The wan neon lights, the protected listening space, the white paint, the fake grass… The whole transported us into an aesthetic universe inconsistent with the everyday experience of the original space, which was dusty and replete with harmful and monotonous sounds.

At this point the dynamic force of the urban wasteland reclaimed its rights. The piece’s fragility provoked a radical reaction and the installation was vandalized on several occasions. As an instance of dissemination outside the gallery space and permitting, among other things, artistic experimentation in uncontrollable contexts, the artist centre DARE-DARE positions itself as the antithesis of the museum context. In choosing to open the “parc sans nom” on each side in an effort to transform this enclosed space into a passageway, DARE-DARE made itself the instigator of meetings and exchanges. In this particular context, repression and surveillance were not even considered. Furthermore, the artist did not try to protect the durability of the work in its first form. More as a result of the technique employed, the piece radically freed itself from traditional photography, which aims to capture the present moment and freeze the experience in time.

Wang updated his project countless times, tirelessly reassembling walls and boxes, without nevertheless remaining impermeable to the location and reacting with flexibility to each destructive intervention on Le Nid, which remained in constant evolution. It is here that photography in the concrete sense of the term enters the scene, documenting the process instead of the final result: each stage of destruction, each reconstruction proposal documenting what confronts an artist who performs and repeats different gestures—almost on a daily basis—on an installation that adapts itself to the coveted space. The project’s permeability was admirable. Rather than impose resistance to unanticipated elements that deteriorated the initial creation, Wang’s intervention was of the order of persistence in this urban ecosystem. In taking an interest in the everyday, the artist did not seek to immortalize the present moment. He propose instead a series of snapshots that do more legitimately justice to the invested location, both temporal and immutable. In creating a poetic, sound and light experience in this specific space, Wang has first and foremost re-transcribed its breath. Breathe in—the boxes were arranged in broad daylight. Breathe out—they were dispersed in the middle of the night.4 4 - The piece was destroyed twice at night and once in broad daylight. The ordeal of the park finally transformed the breath into breathing. This implied that a site has a life of its own, that it is still capable of engulfing and surpassing all attempts to control it. From the sumptuous unveiling of the project at the opening to its discreet ending—cartons soberly folded and piled up below the underpass on the day of the work’s dismantling—the artist allowed us to experience the installation in its completeness. Although at first it was meant to be in harmony with only its physical environment, Le Nid was thus able to account for its human environment. Anonymous volunteers worked hand in hand in the daytime throughout the exhibit. This artwork thus bore witness to the space without ignoring its occupants.

The artwork Pour l’instant, l’arbre by Joanne Poitras, presented in December of 2004 at Art Mûr gallery, raises other issues related to this discussion. The artist developed a subtle practice integrating harvest in a creative process not limited to one medium. For this project, Poitras first chose a hybrid poplar whose leaves she endeavoured to collect methodically at the time of their annual fall in autumn. The leaves salvaged by the artist were later dried, meticulously sorted by size, and finally assembled one by one to form an organized pile of leaves. There was no platform, only a little mound on the ground. All the leaves of a tree—from which it draws its strength during the course of the seasons—a whole year’s worth of leaves was then reduced to an organized heap. The size of the end result astonishingly contrasts with the idea that we may have of the quantity of leaves borne by a tree (close to 250,000 in some cases). It rather has to do with their number, the time span of their growth, their staggered fall, the leaves’ drying time, the time it takes to organize them, and the installation time. All of this in the face of the irrepressible urge to throw oneself in the pile: the desire to satisfy a gratuitous, immediate pleasure.

photo : Yolaine P. Boulianne

It must be noted here that the presentation space is somewhere between two extremes: the museum and the public space. We are in a space adjacent to a contemporary art gallery. Contrary to artworks presented in the public space, those presented in this specific context bathe in a respectful aura. Pour l’instant, l’arbre runs less of a risk of being vandalized. However, the fascination exerted by this project presented without surveillance resides precisely in the ease with which a movement, even if accidental, could radically destroy the result of such delicate labour. Furthermore, during the opening of a first version of this piece then called La butte at the CDEx at UQÀM, the artist recalls how a young man, likely fascinated by the work’s fragility, spent the evening simulating gestures that could lead to its destruction. A third version was thereafter presented at the Centre d’exposition of Rouyn-Noranda. There, the janitor doing maintenance in the exhibition hall accidentally damaged the piece. Never imagining that a sculpture could be so fragile, he apparently tried to move it. Did the absence of protection (a display case or a warning sign) signify that the artwork was not fragile?

In the case of Le nid and Pour l’instant, l’arbre, the possibility of individual intervention is strongly emphasized. In the face of these fragile pieces, the individual is confronted by his or her sense of responsibility towards unique artworks and, by extension, towards the other. If the impression of fragility given by the Mona Lisa under surveillance underlines the already lost battle for immortality, a number of works today openly accept the potential limits of their life spans. And so, fragility goes further than the ephemeral in that it confronts us to our power of destruction. The possibility of free will that Le nid and Pour l’instant, l’arbre impose generates a sense of vertigo for he or she who becomes aware of this. In both cases, the artists deliberately offer their works as fodder to the “irresponsible children” in each of us, who is silenced by a more or less developed superego according to given circumstances. This absence of protection in their installations, which invites affect, situates itself as the antithesis of the conceptual Buren, who tries to keep control of the conservation of his works beyond their creation and sale. The confrontation of these radically different conceptions therefore allows us to create a link between the creator’s disavowal of control over his or her works once installed and the possible power of the spectator over the exhibited pieces. We can understand that this second equation, being of the affective order, radically opposes itself to Buren’s ideas. It potentially leads to an assumed choice between the respect and the destruction of the pieces in question. From the artist’s humility that such risk-taking supposes arises an experience that finally removes us from our illusory relation to immortality and brings us to the tangible reality of our initial fragility, individuals that we are, continuously confronted with our connection to the other.

[Translated from the French by Vivian Ralickas]