In representation that is power, in power that is representation, the real […] is none other than the fantastic image in which power will contemplate itself as absolute.

Louis Marin, Le Portrait du roi

Have artists taken part in the popular uprisings that we’ve been witnessing since the Arab Spring? Have these events given rise to renewed activism in art? Artists’ interventions on behalf of political parties and movements in the twentieth century have been largely disappointing. In the end, either their initiatives turned out to be artistic posturing or their political engagement overpowered their creative work. Such prior experiences suggest that art and political involvement are hard to reconcile. And yet we seem to be witnessing renewed commitment in art, motivated by a need to support people rebelling against their countries’ leaders.

Such is the case with the Foundland1 1 - www.foundland.org collective, created in Holland in 2009 by Lauren Alexander and Ghalia Elsrakbi, whose work actively supports the rebellion in Syria, Elsrakbi’s home country. Their latest project, titled Simba, the last prince of Ba’ath country, consists of decrypted propaganda images disseminated by the “Syrian Electronic Army” through bogus Facebook and YouTube profiles. Messages of massacres in Syria are relayed in an online war in which the dictator is presented as a saviour by fictional fans. The artists’ work consists in foiling these manipulative strategies by bearing witness to them before their art world audience, and beyond, via their own presence on the Web. Foundland is thus grappling with an issue that has always concerned artists: the representation of power, or, in Louis Marin’s terms, the way leaders endow themselves with representations that transform their authority into absolute power.2 2 - Louis Marin, Le Portrait du roi (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, 1981); Portrait of the King, translated by Martha M. Houle, foreword by Tom Conley (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988), 7. Foundland’s work transposes this line of thought into the heart of current preoccupations, as defined by the rapid and massive dissemination afforded by new digital media.

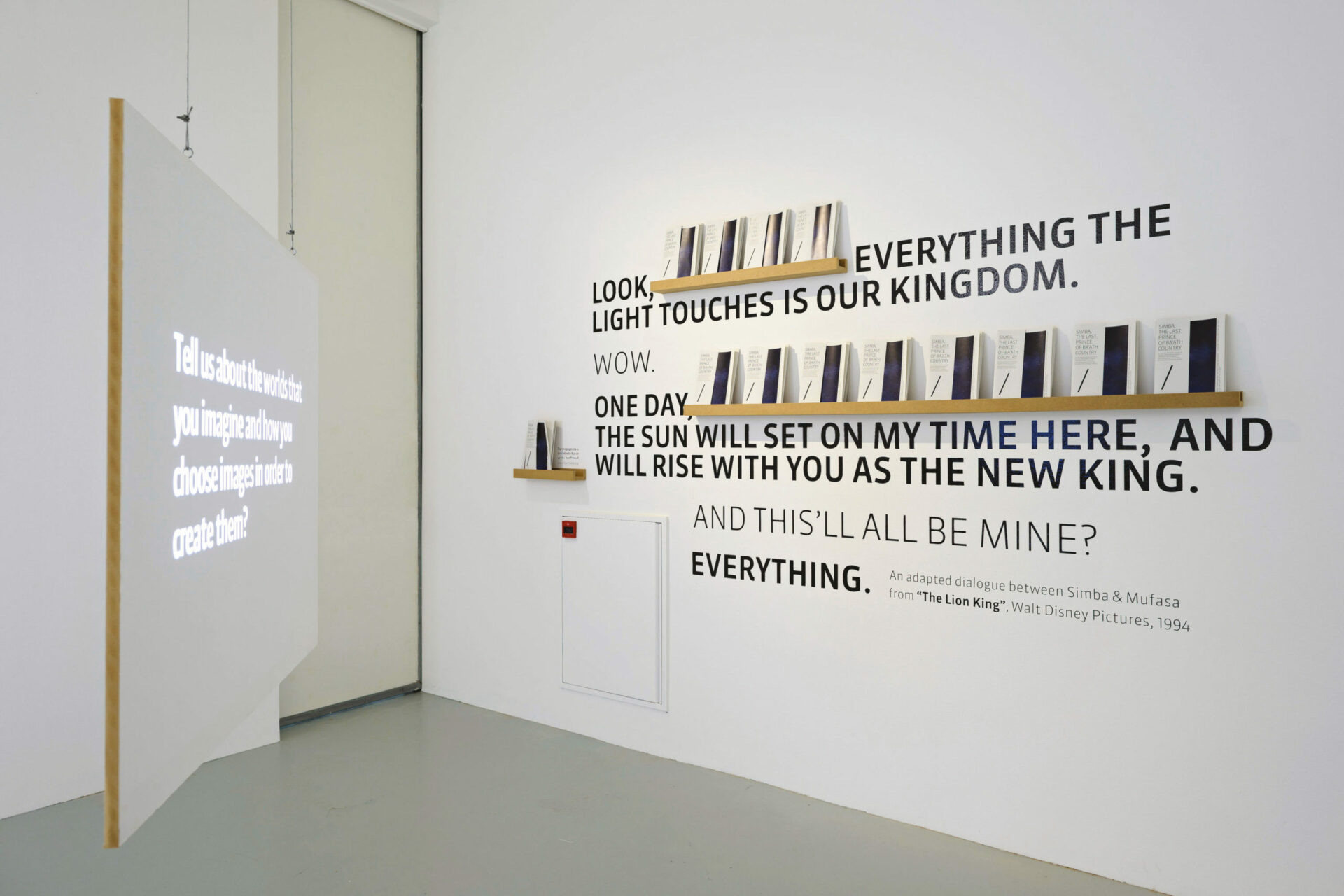

vue d’exposition | exhibition view, BAK, Basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2012.

photo : Pieter Kers

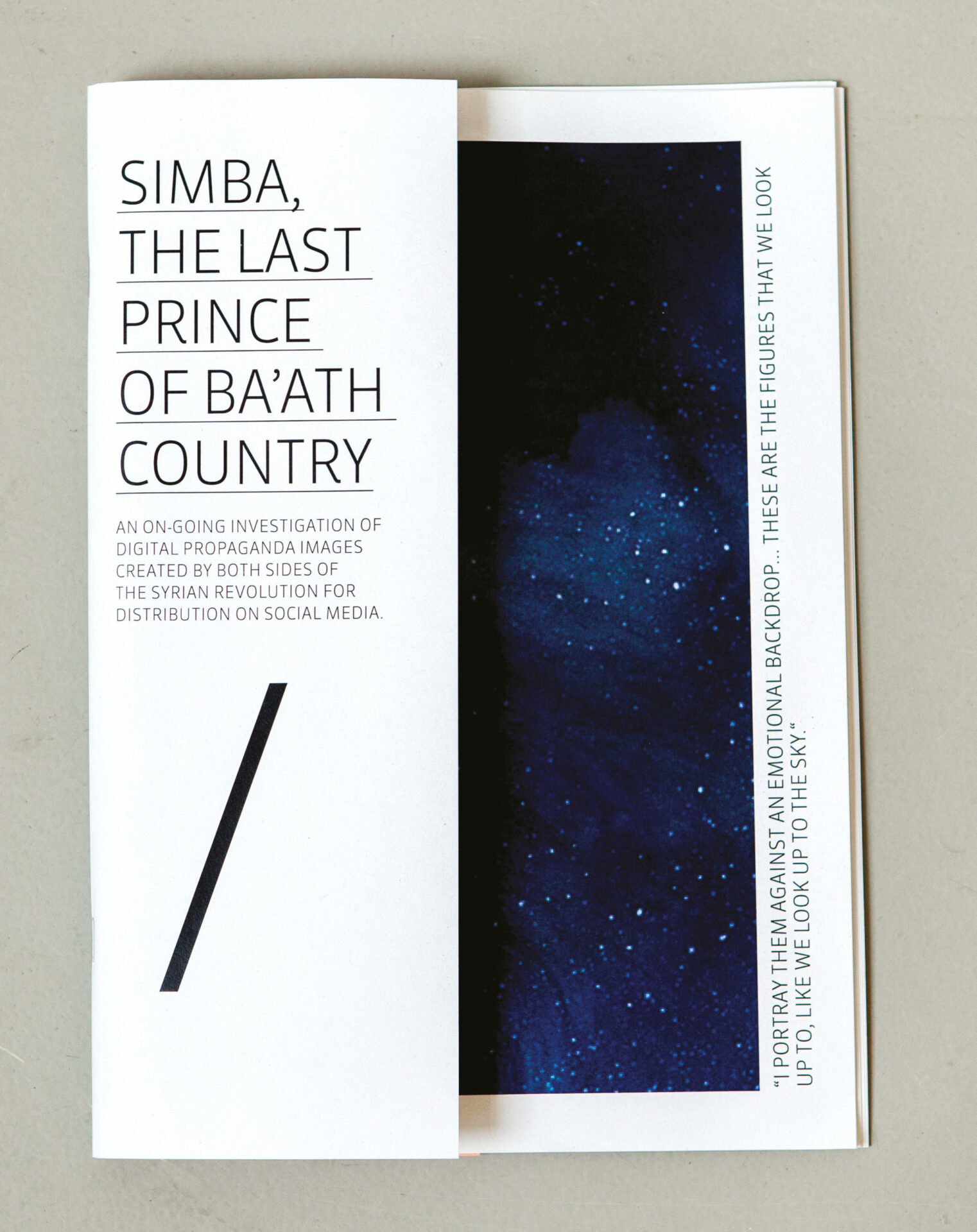

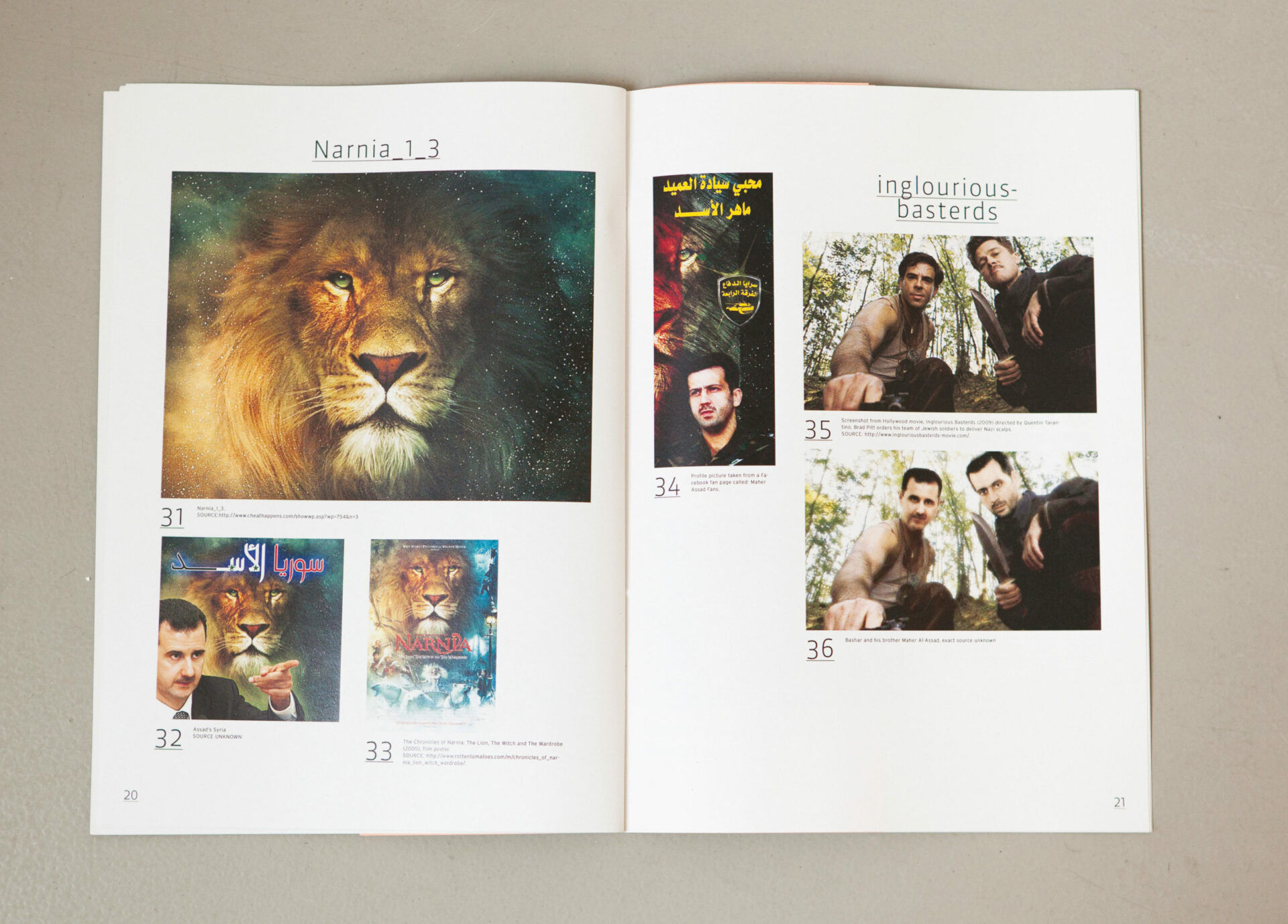

Composed of an installation and a self-explanatory publication, Simba, the last prince of Ba’ath country (2012) follows in the image-collecting tradition of archival artists. The Foundland duo recycles images as other artists have done in recent years, some with similar concerns; one thinks of Walid Raad who rewrites Lebanese history, in part by using found images.3 3 - See, for instance, Vanessa Morisset, “The World as Representations: Collecting and Collating Images,” esse no. 71 (Winter 2011). Foundland, however, is concerned with images of a very particular kind. In Simba, the last prince of Ba’ath country, the artists collect and examine the iconographic sources of curious photomontages glorifying the Bashar Al-Assad regime. They reveal a surprisingly basic method of construction: simply using grandiose images mostly copied and pasted from Western culture — even its worst movies and blockbusters — on which portraits of the Syrian leader are then overlayed. These images are disseminated on the Web, including Facebook profile walls, to give the world the impression that people support the current leadership. The crudeness of the images goes unnoticed in the flow of information. One of them, for instance, shows Al-Assad in a setting from a poster for The World of Narnia, replacing the knight brandishing a sword next to the lion, the hero of the movie. Seemingly incongruous, the connection is actually perfectly in tune with the personality cult surrounding the dictator, capitalizing on the fact that assad signifies “lion” in Arabic. The Foundland artists have in fact titled their work Simba, the last prince of Ba’ath country to reinforce this connection of the Syrian leader with the king of beasts, “Simba,” the name of another cinematic lion, from Walt Disney’s The Lion King. This slippage of Al-Assad into Simba is indicative of the sad state and Ubuesque quality of Syrian leadership.

Other images found by the group stage the dictator in more bizarre contexts still, given his values. Foundland identified a scene from Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, where Al-Assad appears with his brother. Doubtless the only function of such an image is to take advantage of the film’s popularity, regardless of its content or point of view (the film’s protagonist is a Jewish enforcer!), to influence public opinion and present Al-Assad as a hero like the actors in the movie. Another representation is more surprising still: in a religious Christian image, the Syrian leader replaces Jesus confronting Satan, who, naturally, is coiffed by an Uncle Sam hat. Al-Assad is also shown as a medieval knight, or in a radiant sky suggestive of Paradise. Foundland presents these images as a slide show running between two white flags ironically inscribed with two slogans on family and the nation. The images are also reproduced in a publication, accompanied by a text that elaborates the artists’ approach and a fictional interview with a pro Al-Assad Web user who creates propaganda photomontages. These texts tell us a lot about the power of the Internet in a civil war where, alongside the physical war, each camp seeks to discourage the other by showing off its popularity with a barrage of “likes” and friends.

Ba’ath country, couverture | cover, 2012.

photo : Frederik Gruyaert

double page | spread, 2012.

photos : Frederik Gruyaert

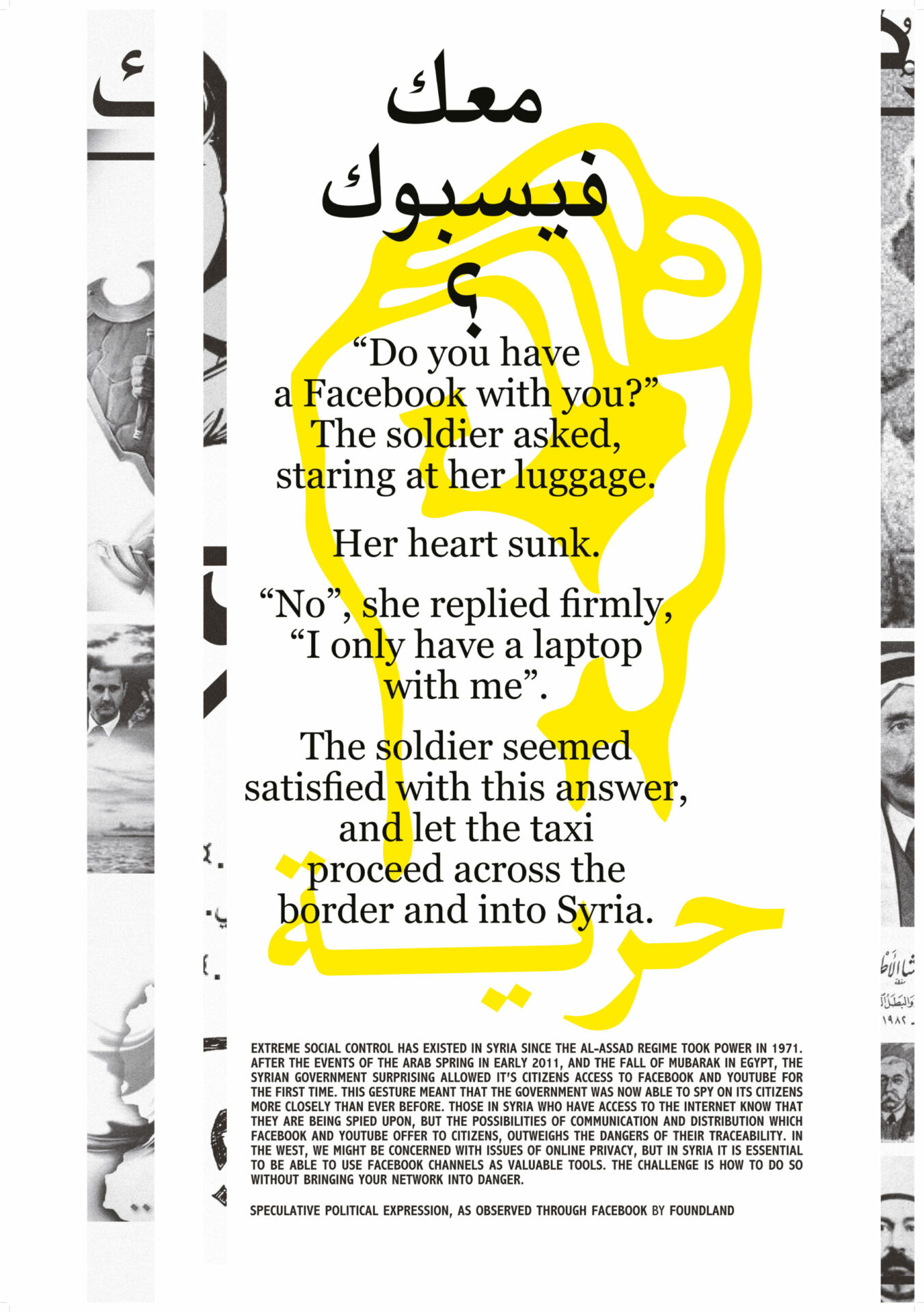

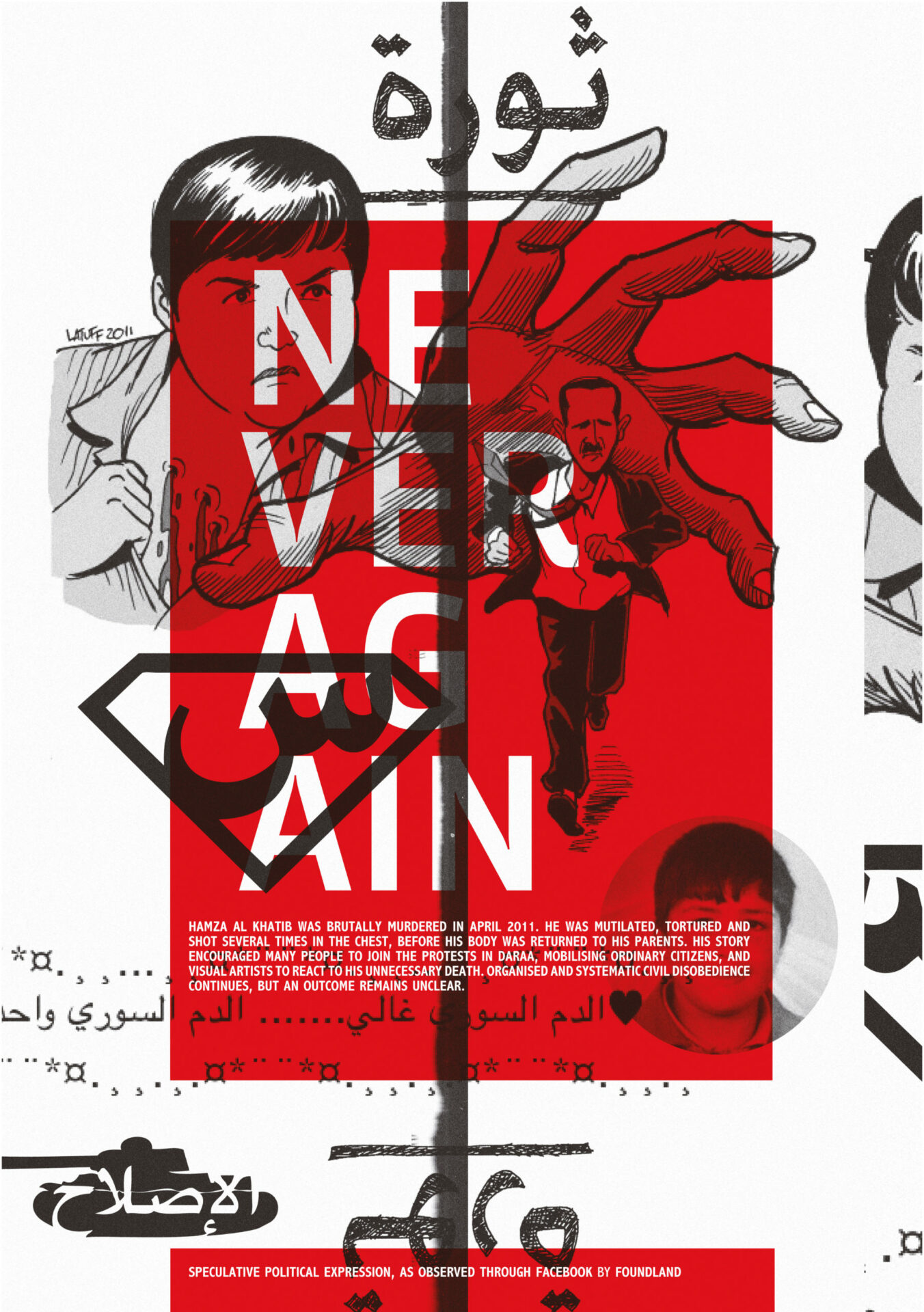

In Simba, as in previous works, themes of psychological struggle on the Web, Facebook in particular, lie at the heart of Foundland’s concerns. Unlike most artists whose work is inspired by social networks, Alexander and Elsrakbi focus on its dark side. The Internet is often cited as an instrument of rebellion that can spread peoples’ stories beyond borders, allowing them to freely express opinions and organize protest groups. Artists connected with countries at war, whether they are at home or in exile, use these resources in their creations. Hiwa K, for instance, an Iraqi artist living in Germany, in his moving performance, Cooking with Mamma, has visitors in the exhibition space help produce a traditional recipe that is explained by his mother via Skype in Irak. Instantaneously bringing his cultural heritage and emotional connections into the world he currently lives in, the artist reveals the Internet’s meliorative function as a communications medium.4 4 - www.hiwak.net/home/ As Foundland points out, however, this medium can just as easily be used for nefarious purposes. As they write in the text accompanying Simba, the Internet is under constant surveillance. The artists say that when they pass through the Lebanese-Syrian border, they are asked if they “have Facebook on them.” Yet Facebook is allowed; the regime has in fact authorized it precisely for the dual purpose of spying on activists and disseminating counter-revolutionary messages, for the benefit of Syrians and foreigners alike. The authorities know that through Facebook, their discourse reaches further into the private lives of a very large audience, which, even if not personally convinced, may be led to believe that many others are. At the Utrecht Academy Gallery in 2012, Foundland organized an exhibition on this theme titled Watching Revolution through a Hole in the Wall, which brought into the space documents and notes Ghalia Elsrakbi received in her Facebook account. They consisted of messages, photos, videos, with comments and responses revealing the duration of the digital conflicts between opponents and supporters of the regime.5 5 - Along with the Facebook elements, the exhibition also presented a bag of ping-pong balls on which were written pro- and counter-revolutionary slogans, alluding to an action organized by activists who, one night in the streets of Damas, distributed similar balls — easier to get hold of than conventional banners. Faced with censorship, activists are forced to invent original solutions to express themselves. This exhibition continued a reflection the artist developed in a conference given the year before in Amsterdam, rather straightforwardly titled Facebook: a revolutionary tool? Here, Elsrakbi gave particular attention to web users’ profile photos and what they revealed about their political stance, particularly the Syrian flag, of which she collected numerous modified versions, with drops of caked blood, black or red stripes of various thickness… Such research demonstrates the Foundland artists’ iconographic skill, as they cull the most significant images from the digital flux.

de la série | from the series (Dis)Orientation, 2012.

photo : Foundland

de la série | from the series (Dis)orientation, 2012.

photo : Foundland

The power of images and their paramount role in conditioning thought is of particular concern for the artists. In their fictional interview with an Al-Assad supporter, published in the booklet accompanying Simba, the last prince of Ba’ath country, they have him say how the images he saw as a child, at school, had conditioned his adherence to the regime: “I was always fascinated by the leaders of our country. When I was a young boy at school, we used to look at the large paintings in the school hallways. These paintings were so detailed, and so beautiful. They depicted in a wonderful way the leaders of our country. When I saw those images at my school, I was inspired. I think this is what led me to become an artist.” By the subverted means of this make-believe interview, Foundland materializes the outcome of its reflections on the power of images in mental representations. The character’s words sum up the consequences of years of political propaganda in Syria, beginning long before the Internet, during the reign of Bashar’s father, Hafez Al-Assad. In revealing this highly effective conditioning — Hafez Al-Assad was long considered, even outside the country, an authoritarian but fair and patriotic leader — the artists highlight the urgency of decoding the images and of distancing oneself from them to preserve a critical perspective. There lies the significance of their research into the iconographic sources of the images disseminated by Syria’s electronic army, which they present in didactic fashion, juxtaposing the photomontage with the original. With their training in graphic design, they dismantle the visual communication strategies operating through these images. In other works, their interrogations rely on the effectiveness of page layout, as in their (Dis) Orientation Poster Series,6 6 - Produced in collaboration with the Italian journal Krisis, engaged in a reflection on the responsibilities of graphic designers in the context of the current (and what the editors deem permanent) crisis. www.krisismagazine.com. which gives shape to narrative snippets found on Facebook or written by themselves, slogans, historical events, along with emphatic graphic symbols like a tank or a raised and clenched fist set against swaths of vivid colour. Foundland thus draws on the tradition of the revolutionary poster while reaffirming its connection with the contemporary world in the ceaseless deluge of messages and images, whether authentic or fake.

At the confluence of sociopolitical enquiry and artistic creation, of activism and design flair, and of the artist’s transformation into iconographer, Foundland’s work shows that political engagement in art is still possible. For in one aspect of these conflicts, namely electronic war, in Syria and likely elsewhere as well, artists specialized in digital imaging become indispensable in helping us to hone our vision.

[Translated from the French by Ron Ross]